Ruth Calland: Artist of the Month, September 2025

Ruth Calland, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

For this month’s interview CBP member Ruth Calland talks about her solo exhibition, ‘This Is All The Treasure We Can Have and Hold’. The exhibition explores notions of transforming and non-binary beings within evocative paintings of figures merging with landscapes. They include ranging references from early 20th century vampire cinema to 21st century TikTok culture.

CBP: Your solo exhibition ‘This is All the Treasure We Can Have and Hold’ is on show at the 20:21 Visual Arts Centre, Scunthorpe until 20th September and presents several series of works depicting humans merging with nature. There is a range of colour and emotional tonalities, from the notion of fear and struggle to something more harmonious with a sense of independent spirit emerging from it.

The latest work explores the notion of ‘Transecology’ and ‘gender-liminal subjectivities through images from popular culture.’ (Cussans Moran, 2025.)

Can you introduce the title and origins for the themes explored in the show?

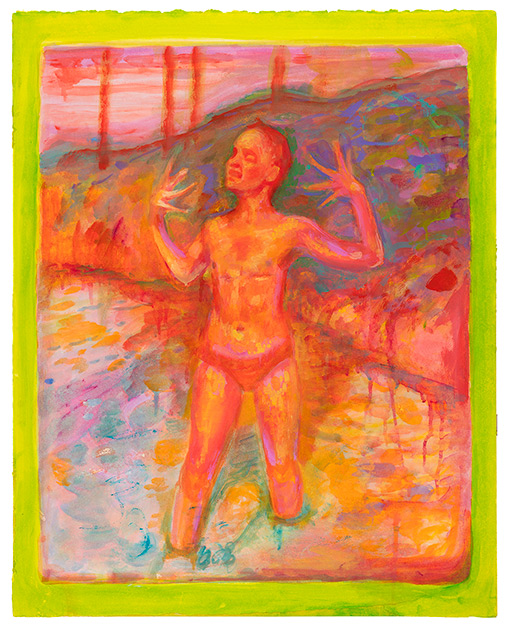

RC: There are two bodies of work in the show, the first is called Vampyre Country, and contains a mood of anxiety around being changed, infected or bitten by something monstrously transforming. The second set of work is called Pin Ups, depicting transgender and nonbinary people situated in the landscape, who are also transforming, or moving in a gender liminal space, but who embrace this freedom and ongoing sense of expansion, or emergence. So something loosening happens in between these positions, a letting go of fear of the Other, in other people but also in ourselves, which is the point of the show. Not everything that comes out of the shadows belongs there.

The title for the show is a line from a children’s song about valuing the plants and wildflowers that children see in their daily lives – daisies, buttercups, speedwell. When I was a child in Scunthorpe the whole school would sing it together at assembly. The fact that an adult had taken the time to write a song about what children experience seemed quite radical. And the idea of valuing what is either overlooked or diminished by others, is the point of my new body of work. It might seem curious to bring a child’s perspective into a show about transgender identities, but most trans people describe knowing from an early age that their assigned gender is not the one they relate to. My personal experience of being a tree climbing tomboy was enjoyable, but for people with gender dysphoria, there can be an ongoing existential crisis from an early age.

The exhibition is rooted in the idea of True Nature rather than ‘given nature’. Nature as creative evolution, not being static or fixed, and instead being aligned with a continually emerging sense of authentic self. When gender non-conforming people express themselves in diverse ways, this is a human trait to be cherished, like wildflowers, that grow where they can, are resilient, and are continually evolving. Diversity ensures the survival of any species, and is intrinsic to the success of organic life. The new field of transecology explores ways in which transness embodies naturality and leads us away from hierarchical and therefore oppressive views and practices in relation to gender, but also in relation to species, culture, race, and environment/biosphere.

CBP: The push-pull between the freedom and restriction of body and spirit which are underlying connotations of the work, are also a formal exploration of figure / ground relationships in painting practice. Can you discuss this aspect in your work?

RC: In the Vampyre Country series, I reference stills from early vampire films: actors are portrayed in various states of capture, anxiety, struggle, or near-death. One reading of vampire film narratives sees parallels with transgressive personal growth experiences, which defy convention and break free from oppressive societal norms. In the film I Saw The TV Glow (Jane Schoenbrun, 2024) a young man is unable to come to terms with his trans identity and has a dream in which he is buried alive in a coffin – a terrifying representation of what it feels like to be trapped in a body that doesn’t feel right. I think that the sense of the unknown/ ‘Other’ is never without judgement (especially the internal Other), and it takes a leap of imagination to see that the other might actually represent liberation from the societal mores which canoppress all of us. We are therefore often tantalised and excited by the forbidden other, hence the magnetism of the vampire, and likewise, the dehumanising fetishisation of trans people.

The figure/ground relationship in both sets of paintings suggests the figures are both emerging from their environment and possibly being absorbed at the same time, produced and simultaneously reabsorbed, emergent and fugitive. In the second series, Pin Ups, the figures have moved into the light, but still have that quality. I like the idea that the Pin Up paintings are a little like kaleidoscopes, caught at a particular moment where a figure comes into view, but that they may slide away at any moment, under a slab of jewelled sky, or fragmented between the lines of trees and branches. In Dissolving with Swans I wanted to explicitly bring this idea that the human in the landscape is one indivisible alchemical system in process. That everything can align with anything else, and constant movement brings greater connection and cohesion. Humans, animals, plants, minerals, nature, landscape – all are indivisible – the ecosystem is a matrix in which everything is connected, and in a process of decay and renewal: everything is constantly morphing into everything else over time.

CBP: Can you talk about the depiction of nature in your painting in relation to your references such as noir and gothic horror cinema and other sources?

RC: I’ve spoken about this in the previous interview you did with me, looking at the connection between vampire films, Covid 19 and a fear of contamination, in relation to my Vampyre Country work. At that time we experienced feeling exposed and vulnerable: we didn’t know where the danger really was, or who the perpetrator was – a life form just wanting to survive, nature’s revenge, or a human-made danger.

Then, despite many people rediscovering a connection with nature, we saw that there was no such thing as ‘natural’ outcomes from the pandemic, only the inequity resulting from the legacies of colonialism and capitalism – such as uneven distribution of the vaccines, and much higher rates of mortality in BIPOC people, more prone to underlying health issues. These realisations revealed the real horror.

The sense of hierarchy, wealth and power hoarding that seemed natural once, is now being more widely challenged and resisted, through a different idea about the naturalness of working together in compassion towards fairness and sustainability. Trans people in particular challenge the existing hierarchies, which depend on binary thinking of all kinds. So in my work I’m attuned to resisting the unnatural horror of the status quo and its reactionary violence, particularly against trans people. The Pin Ups use TikTok videos made by trans and nonbinary creators as a starting point, and the ones that capture my attention are those where a natural landscape setting of some kind has been used, emphasising the naturalness of gender diversity.

Dissolving with Swans (#aprilashley) oil on paper on board, 76 x 61cm, 2025

Study for Dissolving with Swans, oil on paper on board, 42 x 30cm, 2025

CBP: The dark green hued Vampyre Country series suggest movement, cropping and zooming in and out in the style of a film still or storyboard for a film. The most recent technicolour works are portrait format with a distinctive border frame device and are based on TikTok stills. Can you discuss some of the compositional strategies in your painting?

RC: It’s odd isn’t it how most painters, including myself, use a rectangle as standard, and I think I’ve always felt that as something I want to soften. Perhaps as a response to this, I’ve usually avoided straight lines in my work. Another approach is to soften the corners, and I’ve done that inside the frame often, by using the ‘vignette’ device, of darkening them down tonally. In the original Nosferatu (1922), it is there throughout the film. The impact I think is to make a sort of tunnel effect to a dark underworld, as if you are looking through a telescope, trying to bring it closer, but safely protected by distance.

When I began using the coloured framing device of the Pin Ups series, I felt that it was an extension of this softening, also echoing the softened corners of a phone screen. Dominic Mason picked up on this in his foreword to my catalogue, suggesting ‘a portal to a better world’. I found Rudy Loewe’s work (after he and Jasleen Kaur selected me for the Barbican Arts Group Trust Open), and was intrigued by how his coloured wooden frames drew emphasis to the re-framing of colonial narratives in the Caribbean. I felt that my emphasis on a softened coloured border was also about a re-framing, rejecting transphobic attitudes and moving towards a re-humanising and appreciation of the grace and fortitude of many people within the gender liberation movement.

Later, I realised that there was another element involved, and that these paintings had been following a format known to me as a teenager in the seventies – the coloured border framing pop icons within the magazine ‘Jackie’, which would be torn out and pinned to the wall. I was fascinated to remember that many of these idols had also been gender exploratory – David Bowie, Marc Bolan, and others. This was the inspiration for calling the portraits Pin Ups. I used torn paper edges and instead of protectively framing them I glued them to board, so that they would have a feeling of fragility and vulnerability, which I think resonates with the experience of many trans and nonbinary people.

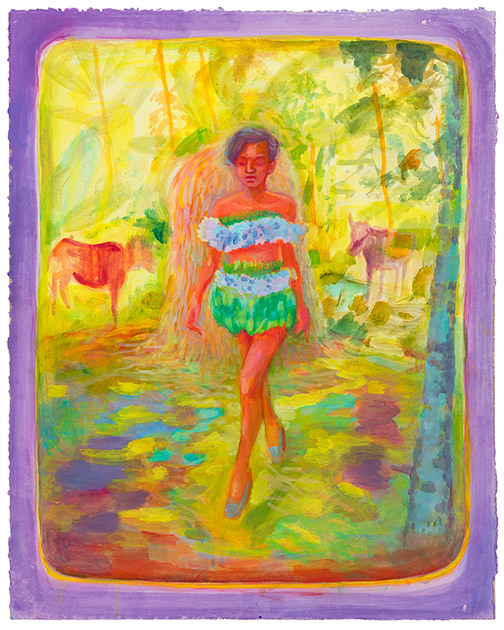

Catwalk with Cows (#neelranaut), oil on paper on board, 76 x 61cm, 2024

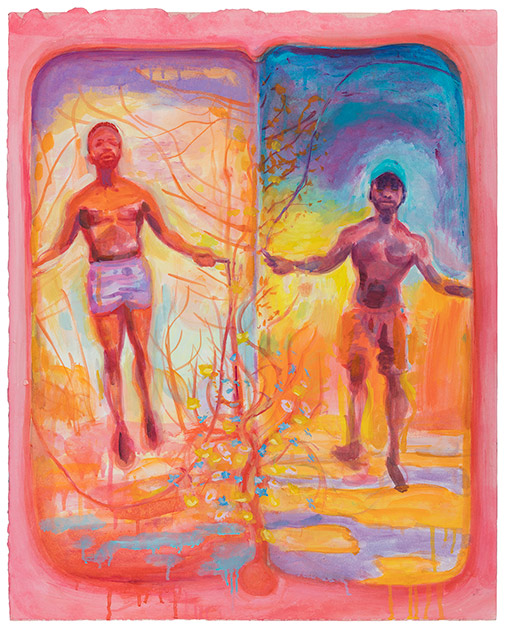

Day 1 and Day 5 (#transcending_d), oil on paper on board, 76 x 61cm, 2025

CBP: Is this the first time you have used social media imagery from TikTok as a basis for your painting? The treatment of the imagery doesn’t make it so apparent and there is a timelessness and Romantic quality that threads together with your other works based on historical film stills.

RC: I started looking at TikTok during lockdown. The immediacy of the form and the vulnerability often shared make it quite raw at times, and relatable. It seemed natural for me to use the videos of gender diverse people I related to as references for my own work. I like to choose a single moment in a video which expresses a combination of vulnerability and strength, and then modify it or add other elements. I think that making work about trans joy – a feeling of being affirmed in one’s gender – has allowed me to think about beauty and harmony in a way that I haven’t before.

I’m hopeful for a kinder future. Tech doesn’t have to be a tool of exploitation, but currently all phone use is contingent on the human rights abuses in Congo and elsewhere, where the minerals inside our phones come from, which makes us complicit. Yet learning to have a voice and use it has been a huge leap for me, and using social media has helped me develop that.

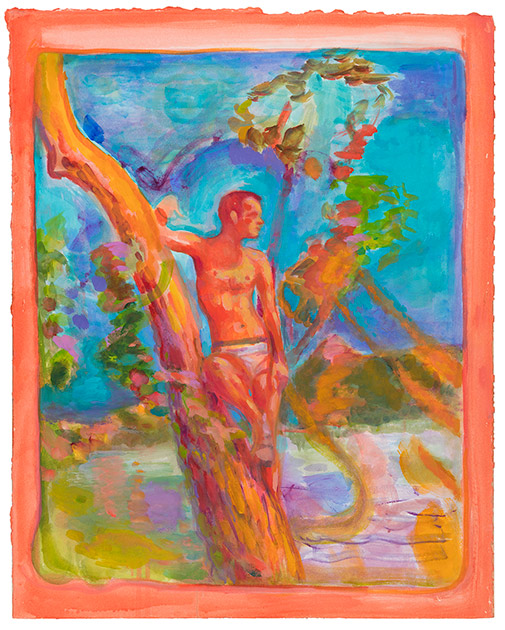

Look After Your Trans Friends at the Beach (#teddytinnell), oil on paper on board, 76 x 61cm, 2024

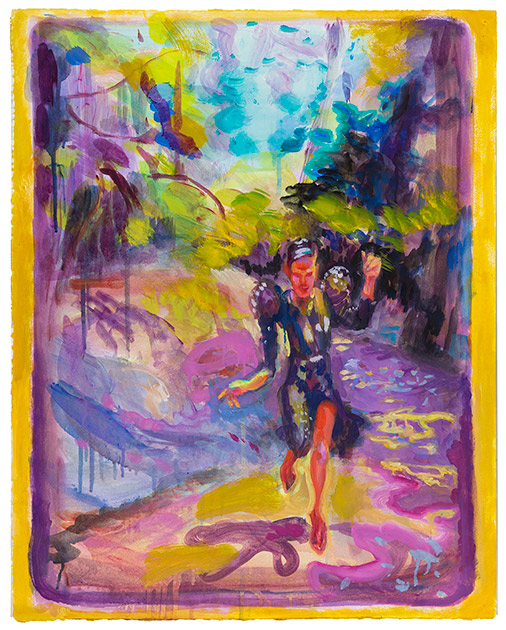

Jeffrey Dancing Outside (#thejeffreymarsh), oil on paper on board, 76 x 61cm, 2023

CBP: Your colour schemes have transformed from the brooding greens of the ‘Vampyre Country’ series to more technicolour and luminous hues, perhaps retaining a sense of something nostalgic. As well as painterly intuition, is the exploration of colour in your work a direct response to the reference sources and evolution of your themes?

RC: As a child I was taken to Australia and lived there from age five to seven. The time I spent there was full of light and colour, gorgeous plants, trees, flowers, birds and insects. I feel that my transition from the darker work, into paintings exploding with light and colour, might have something to do with a return to this time. I spoke about this in a podcast for Geography of Colour with Ruth Philo, and I’m so grateful that she prompted me to explore my relationship with colour. And it was Ruth’s question, ‘what does colour mean to you’, that pushed me to explore colour with greater intensity. My love of Fauvism and expressionists like Kirchner and Schmidt-Rotluff was reignited and I discovered the little known Orthon Friesz.

I recall being enthralled by the bright thermal-imaging colour in the film project Radiant-Fields by Anne Bean at Matt’s Gallery in 2000. Highly saturated and high key colour illuminated beneath or beyond the physical world, and the way the eye perceives it. Another high colour early influence was the films of Fassbinder, particularly Querelle of Brest (1982).

So yes, I feel that the exuberance of authentic expression I’m focussing on, is well served by bright colour but also harmonies of colour, and I’ve really enjoyed developing that sensibility.

CBP: The core themes of identity, gender and subjectivity are encapsulated eloquently in the catalogue essay by Dr Stephanie Cussans Moran. Can you talk about ‘gender expansiveness’ in your work? Has this evolved from aspects previously explored in your painting and your practice as a Jungian analyst, exploring persona and individual and collective unconsciousness? Within the Transecological themes and notions of subjectivity and independent spirit, how do you see yourself in the work?

RC: Whilst I do specialise in working as a Jungian analyst with gender identity, amongst other things, in my art practice I’ve had many phases of making work about gender. In 1986 I made a piece called ‘Nude Self Portrait As A Boy’ which was I think the first thing I made as soon as I got a studio away from college, and the constant presence of tutors (mostly cis men) looking at what I was doing.

One of the films that I’m exhibiting, Loom (Calland and Allen, 2012), poetically documents a series of live events in which I worked with 78 participants, who were each able to identify, name and dramatise both a male and a female side of themselves. It was great fun too.

Then there is the mostly pink painting that I showed with CBP in 2018, Marriage Proposal, which combined characteristics of both male and female dolls into one image, which ended up being a very muscular figure with a head made entirely from breasts. I’m sure that I will continue to explore this subject.

I’m very comfortable with being both non-binary and a woman (my pronouns are she/they). It’s a very personal journey. It’s been important for me to get to know other nonbinary, trans and exploratory people, and making this work has given me a reason to do that, to seek collaboration, and to enjoy mutually affirming collaborations. Did you know chickens can be transgender? I learnt this from one of the people I painted for my show, Max, who cares for chickens on a community farm. I was honoured to meet a chicken who had survived a fox attack that killed the rest of the hens, and has now developed spurs, a male characteristic used for fighting and protecting the flock. It’s well documented that hens can turn into roosters in this way.

CBP: Can you talk about your painting process, the transformation of your source imagery. I wondered if there is still a connection to your earlier series of ‘blind’ paintings where you don’t directly look at what you are painting in order to pull out something other from your inner psyche?

RC: I usually still use blindness, or not looking at the painting, when I feel that the image has become not surprising enough. But I was doing some landscape painting in Sweden last week and I noticed that I was instinctively not looking at the painting at all, just at the tree in front of me. So that’s not really about my inner psyche. It was more a sense of being at one with my surroundings, and my physical movements embodying a process that’s partly projecting and partly introjecting. The painting is the document of that process, rather than a picture of a tree.

With the Pin Ups, the transformation came from the way I was building up the surface with light layers of colour. I was using oil paint onto unprimed paper, which suits me very well, as it’s sucked straight in and I can immediately paint over it. And as the surface builds up I’m making choices about what to emphasise, summarise, make recede, I’m trying to choreograph it as I go, usually without much idea of what’s going to happen next. I really like to be surprised, especially through unexpected colour resonances. I want to be open to rash decisions and seemingly unwise avenues of enquiry, because it’s more interesting to me. And I think that comes back round to a sensibility that encompasses the queer in the sense that bell hooks described in 2014: ‘…the self that is at odds with everything around it and that has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live’. In his great paper Can The Monster Speak, Paul Preciado talks about the sense of being monstrous, of not being definable, of being constantly evolving, unfixed, liminal, not under control. I relate to this sense of the infinite possibilities of becoming rather than arriving; transcending or crossing boundaries, and feeling the thrill of the unknown coming into view.

CBP: The two films in the exhibition ‘Spells of Resistance’ and ‘Lair on the Foreshore’ have a mise-en-scene and patina that links coherently with the paintings. The editing echoes some of your paintings compositions and the soundtrack fits with them also. And you work with freestyle performer Francesca Alaimo. Are they a new development in your practice? How did they evolve from the themes you are exploring?

RC: I’ve always made short films, either exploratory visual collages, or documenting performances, or a combination of both.

I realised that I wanted to work collaboratively with other gender expansive people to make films. So I went with the artist Francesca Alaimo to Epping Forest and she chose a gorgeous ancient tree to move around. I invited her to choose some music and she chose Leonard Cohen’s Everybody Knows, which is full of disillusionment and frustration but also resilience, and she was amazing, she choreographed it all on the spot. It felt like an elaborate ritual and I called it Spells of Resistance.

Then with Robin Stones, I got to know him as he was working at the gallery, and he chose to take me to the foreshore at South Ferriby, on the Humber Estuary. We did a lot of wandering about and slowly he pieced together the actions that were important to him in that place.It was a totally different experience and yet the emotional charge that fed into the film was similarly intense. I felt very honoured to have been allowed into his world, it was a special day.

Working with others, I like to make suggestions and see what happens, not knowing where things will go. Because the Pin Ups are so much about colour, I asked my editor to heighten the colour of Robin’s film, Lair on the Foreshore, and he did a beautiful job. I also took a still of Francesca’s film, and heightened the colour; it is very pumped and yet still has a lot of subtleties. These kind of digital experiments definitely feed back into my painting. I’ve just moved into a new studio so I’m very excited to see what I will take forward, and how a change of scene will affect my practice.

This Is All The Treasure We Can Have and Hold, 20 21 Visual Arts Centre, Scunthorpe, 2025

Installing the show

‘This is All the Treasure We Can Have and Hold’ is on until 20th September and is touring to Hastings Museum & Art Gallery, from 1st April – 1st July in 2026.

Ruth Calland lives and paints in London. They have been a finalist in the 2024 Exeter Open, the 2023 Barbican Arts Group Open, the New Contemporaries and the Marmite Prize for Painting. They are a prize-winner of the CGP London Annual Open, and have shown widely including at Transition Gallery, Studio 1.1, Folkestone Triennial, Vestry House Museum and Flowers Gallery, and curated shows at APT, Walthamstow Wetlands, and Kings Lynn Arts Centre. They were included in Made In Britain, 80 Painters of the 1st Century, at Yantai Museum and touring to Nanjing and Tianjin in China in 2017, and Gdansk, Poland in 2019.

They have been a Boise Scholar, a Rome Scholar runner up, and won a Fellowship in Painting at GLOSCAT, Cheltenham. They are a recipient of grants from The Arts Council, The Henry Moore Foundation, and the London Borough of Culture 2019, amongst others.

Instagram: @ruthcalland

https://www.ruthcalland.com/