Phil Illingworth: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month May 2021: Phil Illingworth, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

CBP: To cover the big broad question first; what is the relationship in your practice between painting, sculpture and installation? Did you come from a conventional painting and drawing background and expand into three-dimensional form, like the tradition of synthetic cubism, or is it I imagine a more complex and nuanced relationship with the medium?

Phil Illingworth: In trying to answer how this came about I had to go right back in time. As a child I thought nothing of moving from drawing, say, to experimenting with objects. They were just different means of expressing myself, whatever was in my imagination. I suppose that means it would have been seamless, I would never have felt that I was changing discipline. Any notion of discrete disciplines will have been something I was taught, as an adult. I’m sure most of us can relate to this.

For a long time my work was almost exclusively figurative, more conventional painting and drawing if you like. Then, a sudden confluence of events and circumstances, along with a reappraisal of what I wanted to achieve with my work, and I radically changed my practice almost overnight. I found myself making work that really excited me – that adrenalin rush, butterflies-pit-of-the-stomach excitement.

My practice does cover many disciplines, but it has a great deal in common with that earlier, boundary-less time. The only rule I have is that there are no rules. However, I do have two what I might call guiding principles. The first is that I make work to satisfy me and me alone. The second concerns painting, but is more difficult to express: the works that I call paintings I determine as such by how I approach them; if there is anything about the concept, or if there is a ‘feeling’ that a work might be more to do with sculpture (say), I no longer treat it as a painting. It is a painting if, and only if, I say it is, but since it relies very much on instinct as well as approach, I have to be confident in my own judgement for it to have integrity. Given the origins of the seed of the idea, that is the most honest the work can be.

CBP: I remember nervously having lunch with the course leader when I started my first teaching job at Uni and he compared himself with me as artists and our interests – he as a conceptual sculptor and me a mixed media painter. The conversation went along the lines of his interest in the form and function compared with my interest in surfaces, which was broadly true. Your works are constructed conceptual objects made with precision, but what significance do you place on your surfaces? And is this an aspect that you can identify as holding onto the concept of painting in your work?

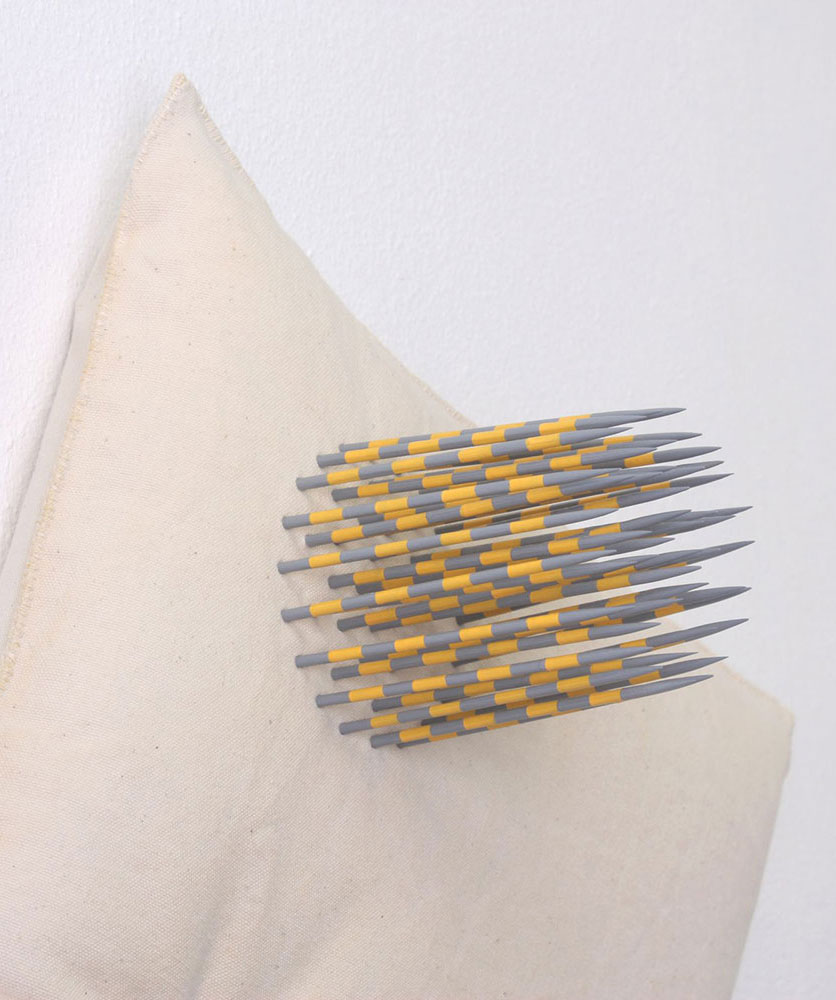

PI: When you break the works down into their component parts, many of them show the same materials and processes as ‘conventional’ painting (by which I mean the entire gamut of liquid paint on a flat surface). The supports I use, the pigments and their carriers, the processes and the finished, painted surface, are all in recognition of the traditions and history of painting.

I don’t particularly eschew the idea of paint on a flat rectangle, but that the works tend to be three-dimensional is more to do with an individual concept than a principle. At the same time I’m thinking of how heavy impasto is paint escaping from a flat plane, for example, and how, historically, sculpture was painted as a matter of course. There is a direct line between the materials and processes in some of my work and polychrome religious carvings – encarnación; literally ‘bringing to life’.

Extra Heavy, Enamel paints, beechwood, canvas, linen thread, wadding, 60cm x 70cm x 17cm, 2017

Extra Heavy detail

CBP: Your works are very individual, each with their own autonomy and identity. Is this a result of them being the result of an initial concept, an independent project and line of inquiry that leads down a specific path determining form and choice of materials?

PI: There are threads or recurring themes which weave through my practice, but I don’t consider works which incorporate these ideas to be of a series. Generally I’d say I tend not to work in series, although the ‘Psychophant’ series is one of those exceptions. To give an example of a recurring theme, once an artist has decided that a painting is finished, and the paint dries, that’s it; short of revisiting and repainting, the process is over. I’m interested in the idea of a painting which is perpetually alterable; I like the idea that a painting can be changed after the event, so to speak. I have made a number of works where I introduced articulations. These can be moved so that the work never appears exactly the same twice. I took this idea further with a piece that moves independently, according to variations in temperature and humidity. These explorations aren’t over.

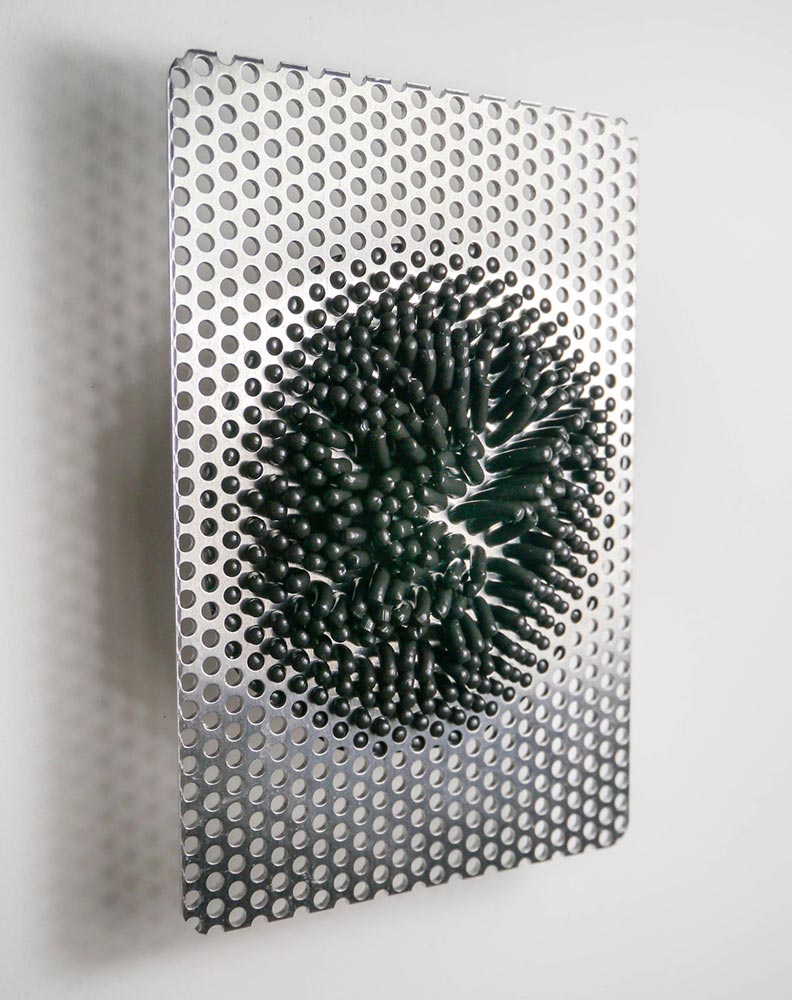

CBP: Could you discuss the background concept and construction of the Psychophant series?

PI: These came about in parallel with my usual way of working. I keep a small sketchbook where I record all my ideas. I sort of ‘zone out’ – when I’m on a train for example – and let random thoughts pop into my head. I scribble these thoughts down in sketch form as a sort of visual shorthand, good and bad, to appraise later. I go back through these visual notes my sketchbook many times, usually when I’m ready to start a new piece.

A number of these sketches had a few things in common; spheres and hemispheres, textures, a sense of pareidolia. I also had a new material I had been experimenting with, a form of PVA used in industrial flooring among other things, and I brought them all together. I have completed four so far, three wall-mounted pieces, and a fourth which is floor standing. The latter is an example of another idea I work with; painting which shares the viewer’s space. There’s something about this notion which is variously invasive and endearing, and everything inbetween.

CBP: ‘A drawing of a room’ 2010 is an earlier work of a cube made from flies and in the notes you discuss the random and perceivably insignificant journey of a fly around a room. Yet to a fly and your initial hypothesis the journey is highly significant and monumental. We know that every small thing is significant in the universe. Could you discuss the notion of scrutiny in your work and in relation to the articulation of the small gesture?

PI: I love the scope of this topic. The fly drawing is one of my favourites, and represents something of a watershed. The pure, small gesture is not quite the Holy Grail, but something like it. I have made a number of very small works, and there are several personally important aspects to them. One of those is the challenge of finding a simple gesture which describes something infinitely larger than itself. Another is to do with the intimacy of the relationship between a small work and the viewer; it has to be close; you can’t stand back and ‘take it all in’. For a moment it is just the viewer, and the work, nothing else.

Ten years ago I invited a number of blind and visually impaired people to come and engage with my work in a solo exhibition. This was a wonderful shared occasion and led to several positive outcomes. One of the things I particularly recall is walking round the exhibition with a man who had lost his sight as an adult. There was a small work called The Martyrdom of St Agatha, a 10cm x 3mm diameter steel rod, mounted perpendicular to the wall, and painted with coloured bands of gloss enamel paint. On touching the work, the man explained how he believed it would be multicoloured because he could feel minute changes in the painted surface. Prior to this I would have said there was little or no difference, but this man’s experience, his perception of this work, proved to me otherwise.

CBP: If we put aside specific backstory to these works and focus on the encounter, they are strange and exotic objects. Yet there is something tangible that feels familiar at the same time as unfamiliar. I could relate some of them to an artist like Helen Marten who transforms familiar, domestic and industrial objects and materials into the new and unfamiliar. There’s also an analogy that could perhaps be connected to the famous Science Fiction novel The Sound of Thunder by Ray Bradbury and the concept of the butterfly effect which explores the hypothesis of alternate realities where things we know are taken apart and put back together differently. Can you identify with this and do you strive to create something unique and unusual from familiar materials?

PI: I’m very aware that my work can have quite an unsettling effect, that there’s a disquieting quality alongside what at first may appear quite cheerful and approachable. The idea of alternate realities underpins my entire practice, in particular ideas concerning conditioned response and how truth can be a matter of point of view. I don’t set out to make work which is unnerving by intent – this is something that occurs as a function of how the work comes about.

I mentioned earlier that I use a sketchbook to note down my ideas. I aim to make the work as close to that spontaneous thought as possible. In the case of ‘Apocalypso’ for example, I scanned the 4cm high sketch and scaled it up to reproduce the shape as accurately as possible. Many of my works are made up of several different components which I make using a wide variety of processes. Although components may be tried for fit, say, the finished articles don’t come together until right at the end. This is the point that I get to see the finished article for the first time, exactly as the viewer would, and often I get quite a shock. “What have I made??” The first few times this happened I was bothered by it, but then I realised that that was sort of the point. I have since learnt to embrace the shock, but it still happens.

CBP: Could you comment on these words in relation to your work; handmade, manufactured and mimetic.

PI: The word ‘handmade’ is quite significant in my work, partly because I’m very fussy, partly because there is a contemplative aspect to the process of making. This is linked at an emotional level to the act of painting in its traditional sense, and it might surprise people how often I use these same skills. The ‘crafting’ of things is very important to me, but I do sometimes wonder whether or not I could hand anything over to a fabricator.

‘Manufacture’ itself comes from the latin for ‘made by hand’, but of course has the more familiar meaning of made by machine or mass production – the opposite of hand made. I often set up mini production lines for multiple components, and I regularly make jigs for repetition, such as the articulated joints, and for accuracy. The high finish I often strive for is intended to look as though it could be machine-made, or manufactured.

‘Mimetic’ I’m less sure about. If any of my work has the look of something else it’s more by accident than design. Sometimes though, once a work is created I can see things – Psychophant II reminds me of a spider’s eyes. One thing I do often aim for though is how the paint transforms a surface – I want it to look like something other than paint. ‘Apocalypso’ is a good case in point, I wanted it to look as if it is made of paint.

CBP: Your work and processes often appear highly technical. Could you discuss some of the workshop equipment, process and materials that you work with?

PI: I use a lot of equipment – a table saw, band saw, several routers, a bench sander, hand-held sanders, lathes, numerous hand tools, metal-working tools, all sorts. In addition to the jigs I mentioned earlier I sometimes need to make maquettes to trial a process or construction (only rarely for aesthetic reasons), and in some instances I have learnt an entirely new skill in order to achieve a particular result. I use a lot of wood, but it’s not unusual for me to research and source a new material for a particular piece.

CBP: What are you working on currently? Do you obsessively work on one project at a time, or do you have a stop start relationship with several projects on the go?

PI: The gestation period for a work can be months, years sometimes, so there is a lot of concurrent thinking and research taking place on several ideas at once. I usually go from the sketchbook to making without intermediate sketches, so the thinking takes place of that. I also tackle a lot of the technical questions in my head, too. When it come to the making, I usually work on one piece at a time.

The piece I’m working on currently is a kinetic piece which involves sound! There are hand-cranked cogs and things, a bit of a departure from the usual but I’m excited about it – assuming it works, of course…

Phil Illingworth has exhibited in the UK, the USA, China, and in Europe including the 53rd Venice Biennale. His works have been selected for the John Moores Painting Prize, the Marmite Prize IV, and the Jerwood Drawing Prize. In addition to private collections, works are in public collections in the UK and China and, in 2019, the collection of the Yale Center for British Art.