Natalie Dowse: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month February 2021: Natalie Dowse, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

Natalie Dowse works from the close examination of the photographic image or extracted film still, derived from the surveillance, documentation and scrutiny of various locations. Carefully selected resource material is either used in isolation, in sequence or spliced together to make fictional scenarios, which form the basis of her paintings.

Contemporary British Painting: For me as a viewer your painting has a sense of silence or muted quality. This could be partly a result of the type of photographic images you paint from and the effect of your painterly process. From your perspective as the painter, can you discuss the shift in tone or meaning from a photographic source image into painting?

Natalie Dowse: There is certainly a ‘feeling’ that seems to be prevalent and threads itself through much of my work. It may be hard to pinpoint, but I like your observation of silence. I think this comes from both a combination of the chosen image and the painting process. Some of the photographic sources I use are my own (usually taken on a mobile phone), some are ‘appropriated’ and some are taken directly from the television screen or my own phone videos. I collect my images this way because it degrades them – they are invariably low quality, flawed or grainy. It exaggerates and mutes the image in a way which intrigues me. It also makes for technical challenges which I enjoy. The paintings always retain a firm ‘nod’ to the original source material, in fact, I sometimes record the resulting glitches or photographic anomalies into my paintings. I also exaggerate or mute the colour further, and adjust and crop the images as necessary to make the image work for me, and sometimes I ‘invent’ for the same reasons.

I am a very slow painter due to the techniques I use, building the image in many thin layers. The polar opposite to the quick speed of a camera and instant image capture. The paintings have a time of their own, in both the making, and hopefully the viewing. I use layering, over-painting and glazing to bring depth.

I’m not trying to reproduce the photographic image: there’s something contemplative about scrutinising an instantaneously captured image combined with the slow process of painting. A unique relationship is formed – something gets added. For me this can manifest itself in a number of ways. Through the making process I often feel that I am somehow taking a past experience as my own, taking ownership of that moment (for example, painting 1970s gymnasts at the Olympic Games), vicariously playing a part. Something different occurs when I use my own images, in this case you have the personal experience and memory of a scene, but then the added ability to observe the photograph so intensely that you can access details you couldn’t otherwise recall. Sometimes, it is the concept behind a series that becomes my most important concern, but there is a common ground whereby the transition from photographic image to painting produces a significant shift.

CBP: A painting or series of paintings taken from stills can present a different kind of narrative to a film or moving image footage they are based on, some of your series are taken from screen captures of films, like ‘Crocodile Tears’ and ‘Cuts’ and ‘Little Girls in Pretty boxes’ based on video footage of gymnastic competitions. Could you discuss how the notion of narrative has developed in your painting? And with your multiple series of works, do you exhibit them as separate entities or have you combined works from different series together to create new potential narratives?

ND: Each frame of a film is seen in very quick succession and in sequence, with the order of events fixed by the story and orchestrated by the director. By distilling these images you pull them out of context, and in a sense slow them right down. Of course, when presenting paintings in series, even if displayed from left to right, you cannot guarantee a sequential reading of them in a gallery space. This is not necessarily my intention, but I do like to play around with this idea when thinking about display. Sometimes series are hung in rows and sometimes scattered in a grid (although carefully planned). In this sense you could argue that any number of multiple narratives and readings could be interpreted depending on the intended order, but also allowing for whichever sequence that each viewer chooses to view them. It becomes a kind of ‘random’ visual story telling that doesn’t have a beginning, middle or end. I know that in a lot of cases this has offered the viewer an opportunity to interpret a narrative personal to them. I have certainly experienced this when speaking with people about my work. I think this may come from common and shared experiences, and the fact that people like to tell their story too – something I find interesting and which I encourage.

You ask if I ever combine paintings from different series: so far this is something I haven’t done. The ‘Cut’ and ‘Crocodile Tears’ paintings are two separate series, but they are very closely linked, both in subject and concept, so perhaps I could consider combining these in the future. I have always felt that these series should be shown together, along with some of my others. Going back to sequence and narrative, the fact that the source materials for the ‘cut’ and ‘crocodile tears’ are taken from numerous films throws up another set of conditions or alternative readings that take them away from their original incarnation. Grouping each moment in time, framed together for their connection but in another context, distances each of them once again from their initial meaning.

As an aside, working in series throws up a recurring dilemma for me, and how the works should be seen (i.e. in their entirety) and whether they need to remain together forever! On occasion I do make stand alone paintings, but I often feel I have more to say – I get obsessed by a certain subject or concept and it is my way of exploring it. This doesn’t mean the paintings can’t stand alone, and for practical reasons they have been exhibited alone or in part many times. However, whether I want them to be seen like this is another issue. Maybe each new combination does create a new potential narrative.

Cut 7, oil on canvas, 46cm x 46cm, 2015

Crocodile Tears 3, oil on canvas, 46cm x 46cm, 2016

CBP: The Cut series, are based on film stills, I think I recognise Bruce Willis. They have a sense of before and after; they are little cuts, but how did they appear? And do the wounds get worse? There is a notion of before and after in the potential next frame / painting. It’s like a dam about to burst. Could you discuss the concept behind this series?

ND: I’m pleased that you have picked up that they have a ‘sense of before and after’, but of course I don’t reveal the before and after in the sequence. Each image is isolated from the context of the narrative that came before and from what follows. In these paintings I have taken the notion of a cut to the cheek as a cinematic cliché. The source material, collected over a long period of time, involved many evenings of disrupted film viewing where I would pause the film and then inch back and forth until I found the exact frame I wanted. I’m fortunate that my partner is also an artist – I doubt anyone else would be quite so understanding!

The paintings parody the visual shorthand used to portray an injury in film and TV. The selected image is carefully cropped and recomposed to focus on the protagonist’s face – often more of an extreme close-up than the original frame. The circumstances surrounding each injury may vary, a cut from an accident or perhaps from a violent act – but of course this is only a cinematic illusion created with make-up, and is merely a painted mark in itself.

These ‘cuts’ are also an unexpected imperfection to the painted surface – I render the cut simply, both referencing the brush stroke and highlighting the violence implicit in the mark.

CBP: The subsequent series, ‘Crocodile Tears’ are black and white paintings. Were the source images/ screen captures they are based on also black and white or did you make a decision to paint them this way?

ND: Similar to the ‘Cut’ paintings, the focus in the ‘Crocodile Tears’ series is on the protagonists’ tears. I deliberately decided to paint them in black and white (the original film stills were in colour) and I also went for a much tighter crop. By stripping out the colour and zooming in even tighter (the ultimate close-up) I was aiming to take the image further out of context whilst also rendering the ‘actor’ anonymous in order to focus more on the concept. I wanted it to be less about recognition and more about the action.

As with the ‘Cut’ series the circumstances surrounding the cause of the tears may vary, but are also merely an illusion. This time it’s down to the actor’s skill to convince us of the emotion, fake as it is.

CBP: You explore a range of view points, from close ups of subjects from film stills, candid views of other people like the ‘Park life’ series to point of view scenes of an observer looking out onto a landscape / seascapes. Do you consciously consider the relationship of your painting to film making and photography in terms of shot making; long or establishing shot to medium to close up and extreme close up? And do you format your paintings in relation to their source material for example a 4:3 ratio from a video screen capture?

ND: Yes, the ‘filmic’ is something I embrace. Maybe not so intentionally at first, but definitely something that has emerged as a strong element. I feel that some paintings like the ‘Between Dog and Wolf’ series are somehow setting a scene, in readiness for something about to happen. The candid shots of people in the ‘Park Life’ paintings become the characters in my own imaginary ‘film’ and the road paintings and seascapes put the viewer firmly in the centre of the action by virtue of their viewpoint. I use both the whole ‘scene’ or crop heavily depending on what I want to achieve and what grabs my attention about a certain image. Some paintings remain faithful to the 4:3 or widescreen formats, some I intentionally compose to replicate that. I like to mix it up a little. For example, I love to paint on a square format. I remember a tutor telling me at art college (whilst I was working on a square painting) that, ‘They had never seen a successful square painting, ever!’. Well, whoopeedoo. I was intimidated by that for some time, because they were a tutor. Now I know it’s prejudicial nonsense.

CBP: Can you discuss your technical process; how you build your paintings, your colour and paint application and approaching the finishing line. Do you ‘edit’ your painting?

ND: I have touched on this, in part, in the first question. As I say I build the image up in layers. I put a lot of emphasis and importance on the drawing from the outset. However, I will edit, wipe back and adjust as I go where necessary. Regarding colour I like to switch from using heightened and exaggerated colour to monochrome, then from high contrast to barely there and faded.

As for the finishing line – I still feel that knowing when a painting is finished is one of the most challenging aspects. There’s a fine line between pushing further to improve something or pushing further and losing it. I know this is something that will strike a chord with most who read this.

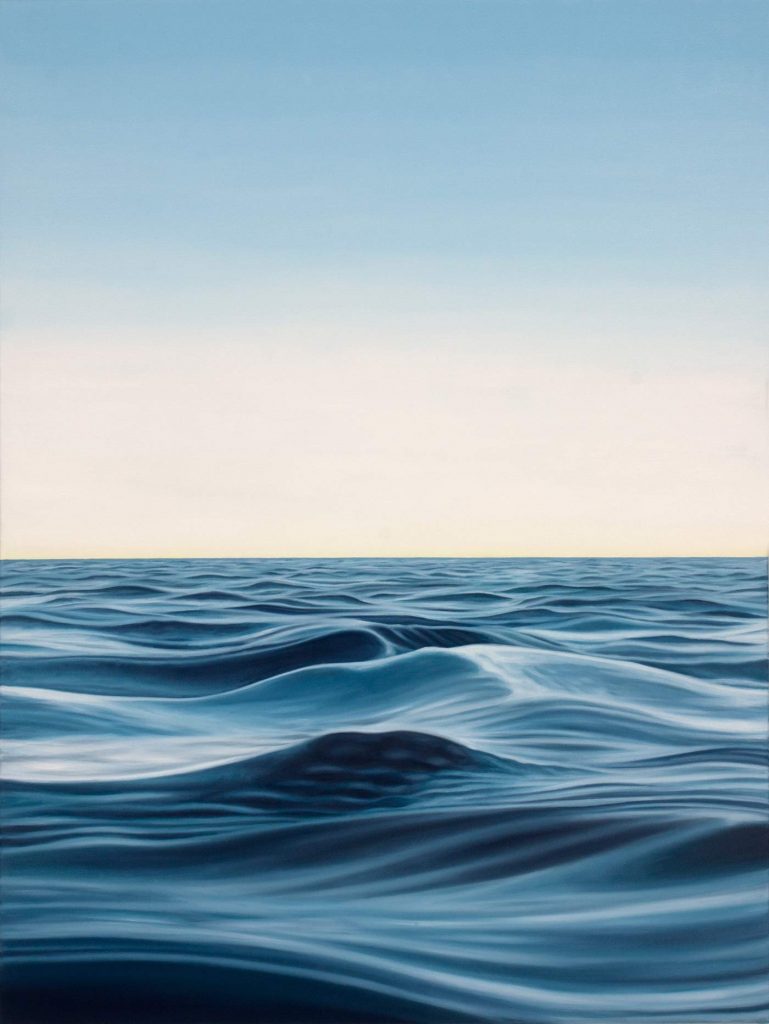

CBP: Your new paintings of the open water ‘Song of the Siren’ and of a fishing nets under the sea ‘Ghost Nets’ create both a feeling of transient calm and ominous sense of threat. The light in particular feels like it could either illuminate further or fade into darkness. Could you discuss these works?

ND: The sea paintings ‘Song of the Siren’ are based in part, on the notion of the Siren from Ancient Greek mythology. The Sirens use their exquisite song to lure sailors to wreck their ships on the rocks after falling in love with their beauty and song, and consequently taken to their death.

Painted from the viewpoint of someone immersed in the sea rather than from the safety of the shore, the subject is both enticing and beautiful, yet hints, I hope, of a latent menace that reminds us of the unpredictability and force of nature. This uncertainty, as you say, could transform the scene in a heartbeat. As someone who has (almost) always lived by the sea and found it both a comfort and a terrifying force, I am also, as a very weak swimmer, very cautious and fearful at the same time.

The ‘Ghost Nets’ paintings take on a different perspective, submerged in underwater worlds.

Ghost nets are fishing nets that have been discarded or lost in the ocean. These nets are almost invisible to sea life, and as they drift around the open seas they entangle marine creatures such as dolphins, turtles and sharks, entrapping them and ultimately causing lacerations, starvation, suffocation, and death: thus becoming a metaphor for the Siren.

I think your question and observation, ‘create(s) both a feeling of transient calm and ominous sense of threat’ sums this up perfectly.

This also leads me directly back to the ‘Between Dog and Wolf’ paintings. ‘Between Dog and Wolf’ is from the French saying, ‘Entre chien et loup’ that refers to dusk, just before nightfall, when the light is so low that it would be difficult to distinguish between dog and a wolf. I find it a very lyrical description of the limit between the familiar and the unfamiliar, and for when for no obvious reason the dark suddenly becomes scary.

CBP: You have an up and coming portrait commission for Fenella Fielding a 60’s / 70’s cult actress of comedy / horror film roles and stage works, who then went into obscurity. It feels like a romantic Thespian story. Can you give any insight about the commission and will it relate to your existing portrait series based on film stills?

ND: Yes, I am currently working on three portraits of the late Fenella Fielding as part of an exhibition that celebrates her life and career. The exhibition is curated and organised by Fionn Wilson, with the assistance of Simon McKay, a close friend of Fenella’s and the co-writer of her autobiography ‘Do you mind if I smoke’. My own three paintings are not yet ready to show – but as you might expect they do have a strong connection to film.

Fenella recorded an audio version of her autobiography, and I have been listening to it while working on her paintings. Listening to her speak (and she had an amazing voice) makes for a really interesting dynamic and an interesting relationship with my paintings of her.

Fenella was both a comedy and serious actor who played most of her roles in the theatre. She was less known for her film roles, which were fewer in comparison. In the wider public consciousness Fenella is probably best remembered for her role as Valeria in ‘Carry on Screaming’ where she had the lead role and double billing with the late Kenneth Williams.

Covid restrictions permitting, the exhibition is due to open in Newcastle in the spring before travelling to three other cities important to Fenella’s career.

Lastly, thank you for your insightful questions and inviting me to be artist of the month.

Simon McKay has also established the Fenella Fielding Foundation and is currently in the process of cataloguing her archive and personal effects. You can read more here: www.fenellafielding.com

Natalie Dowse lives and works in Portsmouth on the south coast of England and has exhibited her work nationally and internationally. Her work is in public and private collections, including the Jonathan Vickers Collection, the Robert Priseman Collection at Falmouth Art Gallery and the Priseman-Seabrook Collection. Her work is also featured on the Art UK website of the UK National Collection.