Abstractions of experience

A essay by Terry Greene to accompany exhibition A Road Not Taken.

Painting and the metaphor of the journey.

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth; (Robert Frost)

Robert Frost’s poem ‘The Road Not Taken’ begins with a dilemma. Out walking, the speaker comes to a fork in the road and has to decide which path to follow. The two roads are a symbolic reference to two diverging choices, posed in front of an individual. Forks and woods are used as metaphorical devices relating to decisions and crisis. Here we find the poet drawing upon universal experiences, such as human travel, to make a complex thought easier to understand. When we define events such as death as a passing and the structure of life as a journey we are using the familiar to grasp the less familiar. But while the commonality and familiarity of travel may be seen by the fact that travel is one of the most common source of metaphors used, the very experience of travel remains subjective. We all experience the world from a perspective. The contents of an individual’s experiences vary greatly with the individual’s perspective, which is affected by his or her personal situation, language and culture and physical conditions. Two people may experience the same event at the same place and time – their perceptions, however, are unlikely to be the same (a room might feel hot or cold depending on the climate one is used to). Nevertheless, and with that in mind, considering actions and events in relation to travel – practically or imaginatively – still offers us a productive means to explore the elusive subject.

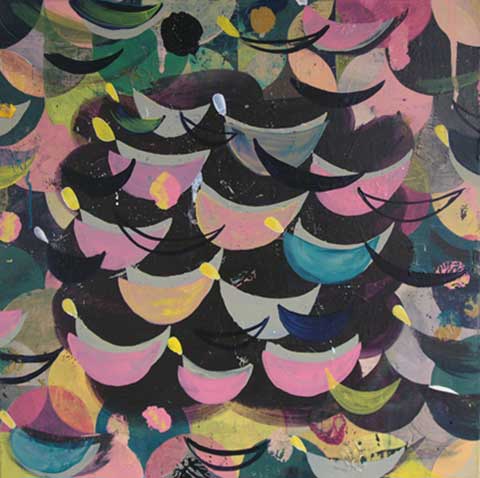

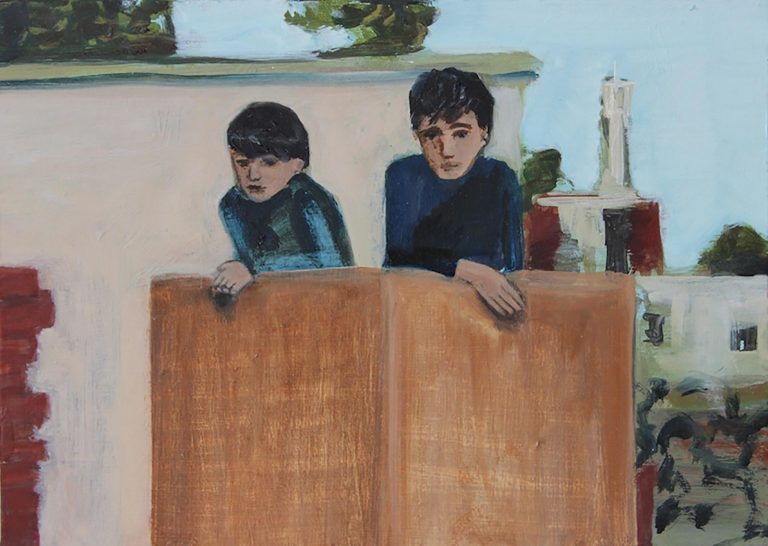

Travel is thought to be a great change-inducing experience because it can provide an ongoing supply of new and novel experiences. We are often more aware of ourselves when travelling and through consciously noticing: being receptive and aware (the necessary steps to rendering our experiences lastingly meaningful). This is the art of travel and, surely, no different from the art of art. When we experience variations in lighting, colours on the walls, different smells, and different types of sounds, they evoke different feelings within us and in turn these sensory experiences influence our responses. We are all highly susceptible to environmental triggers and these triggers can powerfully seed responses in us. The environment the artist experiences influences his or her creative process. Where the artist receives his or her sensations from the world, the viewer of the art object receives his or her sensation from the painting itself. Artists offer us abstractions of experience. If we consider for a moment the physical act of painting in terms of a journey then the art object (in this instance a painting) might be said to describe or embody the territory the artist has been navigating. The art object, a little like a souvenir picture postcard, functions as evidence for a ‘place’ visited, seen and experienced. ‘What is seen and called a picture is what remains – an evidence.’ 1

According to one interpretation of Robert Frost’s ‘The Road Not Taken’ “the title hovers over it like a ghost…[and]…implies that poem is about absence. It is about what the poem never mentions:

the choice the speaker did not make.” 2 In essence, there’s no definitive true path. The other path, and what’s irrevocably lost in not choosing it, reminds us of the important role chance and risk play – both important properties within abstraction – we are free to choose, but we do not really know beforehand what we are choosing between. For the artists and their works in this show the route is similarly determined by a cumulation of choice and chance, and it is impossible to separate the two. Picasso described this process as: “What comes out in the end is the result of discarded finds.” 3 The artists constantly give us cause for thought. Their paintings forcing us to confront the random nature of our lives which is not always a comfortable position.

When confronted by a series of surfaces—the paintings hung upon the walls around the gallery – we attempt to interpret them. These exteriors are the material we are given and they can provide us with perhaps a profound source of knowledge. Like each of us a painting contains its own autobiography; when we stand in front of one we experience it in a moment of stasis, its current iteration. By looking at its surface we may be able to discern its journey, its progress, via a series of corrections where the transformative processes are often perceptible through its pentimenti and trails. They remind us, like an affirmation of the crucial nature of the choices we must all make, of the finality of those decisions and their irreversible effects. At the same time we are viewing the ‘evidence’ of some mysterious process that takes place in the studio. Setting off for new and unknown destinations, the artist’s journey ends with the opposite of what it begins with, reality, and abandoning the fugitive and intangible. We perhaps sense that internal journey unfolding upon the very surface of the painting – the voyage may be a circuitous one, but there are interesting sights along the way. Lines of force and blends of colours clearly show that logic is at work as well as the operation of chance. And as we continue to experience the art object in front of us we might discover that we are allowed glimpses of some occasional moments of hesitation, the odd false start – imbuing the pictures surface with some greater sense of the human presence behind them. The paintings in this show, like postcards, are human, intimate. You know the artist has physically touched them. They are sending you something of themselves.

Terry Greene, 2018

1. Philip Guston, 12 Americans, by Dorothy C.Miller, New York, 1956. p. 36

2. Katherine Robinson, Our choices are made clear in hindsight, Originally Published: May 27th, 2016, www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/89511/robert-frost-the-road-not-taken

3. Picasso, Picasso: Genius of the century, by Ingo F Walther, Taschen, 1986. p. 81