Emotional Spectres: Lesley Bunch’s Abstracted Objects

An essay by Hettie Judah (writer and art critic) about the work of Lesley Bunch the winner of the CBP Prize 2022

This essay was published in the CBP Prize 2022 exhibition catalogue. The essay forms part of the prize.

“…it is usually not an object’s presence but far more often its absence that clears the way for social intercourse.”

from Jean Baudrillard, ‘A Marginal System: Collecting’ (1968)1

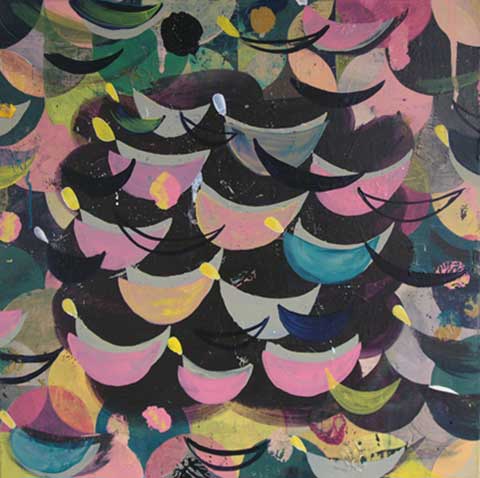

Lesley Bunch’s paintings have an uncanny vibrancy and dimensionality. The colours shimmer, apparently alive with light. They are, superficially, abstract – there is no easy to discern ‘thing’ here, nothing evidently represented. Yet the language of light Bunch employs, with its glimmers, reflections, and shadows, gives the impression of a physical object – something nebulous, translucent, globular, perhaps even iridescent, but a thing, nevertheless. And indeed, there are physical objects linked to each of Bunch’s paintings, but they have endured multiple levels of translation and transformation. What we encounter on the canvas is something like an emotional spectre.

In 2014, during a year-long residency at Wimbledon College of Arts, Bunch put a call out for what she describes as “persistent” objects – things the owners had “invested emotion in”. After a long conversation with each lender, she composed a shadow thrown by the object that in some way interpreted its emotional resonance: images resulting from human encounters, made from the interplay of object and light. Transparent or translucent objects were favoured, particularly those that carried colour, allowing the light to penetrate and dapple, and for the artist to play with colour and pattern. Each shadow was photographed separately from the object that cast it, becoming an abstracted composition in colour, light and shade.

Fascination with sheen and translucency have a long art history. The Dutch Golden Age brought luscious studies of liquid in glass vessels by Pieter Claesz and Clara Peeters: these paintings were a show of dazzling skill, demonstrating the artists’ ability to capture the insubstantial interplay of reflections, light and shade. In 1844 William Henry Fox Talbot photographed three shelves of crystal goblets and decanters against a dark background. With Articles of Glass the pioneering photographer demonstrated the ease with which this emerging medium communicated the form of these transparent objects through the reflected light on their cut surfaces.

The seductive power of patterned shadow was harnessed in a rather literal way in the homoerotic photography of Bob Mizer, many of whose post-war ‘physique’ photos of bodybuilders were composed against light patterns achieved by shining spots through pieces of cut crystal collected by his mother. Mizer’s work in turn influenced artists including Robert Mapplethorpe.

In Through a Glass Darkly (2019) Cornelia Parker used ultra-violet light to cast shadows onto chemically coated plates, turning them into photographic positives, a photogravure process developed by two early pioneers of photography: Fox Talbot and Nicéphore Niépce. Although Parker’s series records only their angled shadows, the nature of the casting objects – glasses, plants and vessels – remain evident. Bunch’s vocabulary of shadow images, by contrast, leaves the nature of the source object obscure.

Over the last eight years Bunch has worked with this shadow archive in various ways, using it as a vocabulary of abstract forms that have come unmoored from their specific meaning to all but her. In the Shadow Language photo series, Bunch Photoshopped the forms into blank spaces in ancient manuscripts photographed at a library in Rome. These were esoteric tomes, some in scripts and languages for which no readers remained alive, but with blanks left by each author in the hope that some future reader might build on their work or solve a perplexing problem. Among the texts is an opera by Aristotle, open at a page of diagrams in which the philosopher is attempting to concoct mathematical formulae for emotions. Bunch’s Shadow Language looks quite at home on these pages, but as with the lines and loops and marginalia that surround them, the significance of the shadow objects is, to us, obscure.

Bunch’s subsequent numbered Shadow Sculpture works are constructed using source imagery that is photographic and Photoshop-manipulated, but come into being during the long process of painting. Bunch describes the joy of moment when she “lets-go” of the source material: “there are many, many layers. How do you know when it’s right? It is to do with the observation of how light works and the way things reflect off each other: making the elements relate and interact.”

Studying at Goldsmiths in the 1990s, Bunch was discouraged from painting (the medium was out of vogue). She spent three years instead in the photographic darkroom and immersed herself in theoretical texts. As a painter, she is still informed by a conceptual methodology: there is philosophical as well as emotional foundation to her work. In 2008 she made an early (monochrome, 2D) series of shadow paintings after a close reading of Jean Baudrillard’s essay ‘A Marginal System: Collecting’ (1968). “It was in that bubble when everyone was obsessed with collecting things,” she says. “I was interested in presenting something as a collection that wasn’t collectible.”

The interest in shadows, the language of codes, engineering, and the digital realm all date back to Bunch’s student work. Her subsequent evolution as an artist has been the slow and thoughtful journey back to painting. The residency at Wimbledon in 2014 was transformative. In that same period, as she worked on Shadow Language, Bunch continued her experimentation with the placement of painted bodies in pictorial space. In the Part series, unspecific fleshy portions of a human body are painted at scale, crammed tightly into the confines of each large painting to the point where they become abstracted. Is this skin or rock? Glorious or gross? Unlike Bill Brandt’s abstracted photographs of nudes and rocks from the 1960s, Bunch’s abstracted bodies are not sexy, nor are they necessarily feminine.

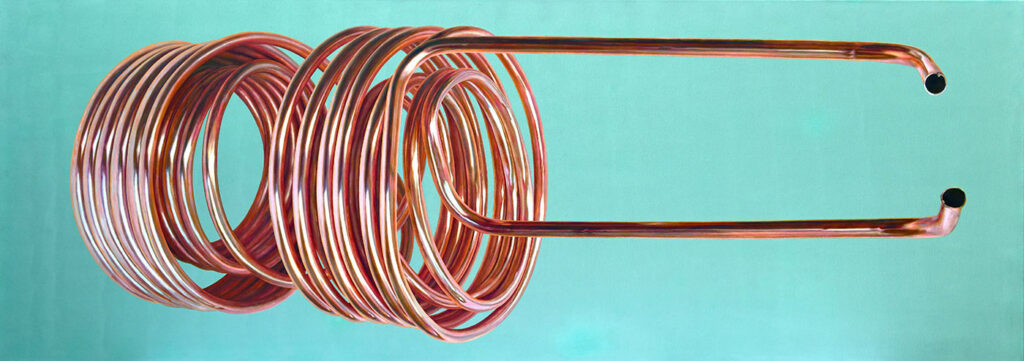

The Exchange paintings likewise play with scale and the sense of weight. Here, otherwise hidden engineering components – coiled heat exchangers – float in coloured space, like sci fi props. Studies in reflective light and intricate curved surfaces, Bunch chases their looped coils of copper and ceramic, building up the surface in thin layers until the tubes seem to glow. As with the Exchange paintings, the Shadow, Other paintings – notably Shadow, Other 1 (2014) and Shadow, Other 3 (2016) – see the painted form float freely in space, like ectoplasm, or life forms of the deep sea caught in the light of a submarine photographer.

In the subsequent Shadow Sculpture series, the forms are grounded, painted by Bunch as three-dimensional forms that themselves cast shadows on the supporting surface. There is an electrical light and heat to these painted objects. They appear to radiate energy from within, obscure forms animated with internal light. The cool precision of Bunch’s brushwork, and the carefully evoked suggestion of directional (as well as internal) light impresses us with the idea that she is indeed painting a physical object from life, but she offers us nothing that we can easily grasp onto or recognise: her paintings are confounding, unmooring.

Bunch is one of a generation of painters who use digital tools in playful ways. Speaking of a recent series in which he combined painting with 3D computer software, the New York-based artist Seth Price described the difficulty of making good art with computer graphics packages: “The machine can produce anything you can imagine, but this just restates the problem of contemporary art. It’s even harder if you want to take it off the screen, because materializing it usually drains the energy. What makes it worthwhile to turn an image into an object?”2 This question of energy is central, too, to Bunch’s paintings – and one of the pressing issues for artists to engage with in our contemporary visual culture. Images viewed on screens have the innate radiance of a backlit display. They can seem to die when printed (or painted) as was all too evident in the exhibition of David Hockney’s 2020 iPad paintings The Arrival of Spring.

Bunch uses Photoshop to play with her shadow archive. For some of her Shadow Sculpture series she digitally laid the images over physical objects, giving them a fiery gem-like quality. Most important of the receiving forms are rounded concretions found on the shores of Lake Superior. Formed millions of years ago within sedimentary rock formations, these concretions are revealed as the softer surrounding stone eroded away. Fitting snuggly into the palm of a hand, they can be carried as good luck totems (indeed Bunch herself often travels with stones from her collection, and has taken a series of photographs in which they appear nestled into the foreign rock of carved monuments in Rome.) To the Ojibwe and other First Nations people, these sculptural concretions are considered manitou – they are thought of as ‘spirit stones’ – objects possessed of a potent animating force within a landscape that is itself sacred. We might thus see Bunch’s Shadow Sculpture paintings as engaging both with an ancient animist tradition, and the complementary philosophical worldview described by Jane Bennet in Vibrant Matter (2009) according to which all objects, even stones, are considered to have active qualities.

Bunch describes the painterly process of departure from the source objects as one of “giving it back to the viewer, presenting it as meticulously as I can as an object in itself.” Rather than bringing together symbols or elements that might point to a narrative or deeper meaning, she likens her paintings to Haiku poems or Buddhist koans – paradoxical statements or questions posed to perplex and encourage thought. This is not painting that delivers an easy punchline, but art that might invoke a certain feeling, or provoke contemplation.

Hettie Judah

1. Jean Baudrillard, The System of Objects (first published as Le système des objets, 1968) Translated by James Benedict ©Verso, London, 1996.

2. Seth Price in conversation with Mark Godfrey during the exhibition ‘Art Is Not Human’ at Sadie Coles, Kingly Street London, May 2022.

Purchase the catalogue that includes all 17 shortlisted artists and the essay by Hettie Judah.