A personal reflection on Threads:

Two Generations of Painters through Time

Written by Robert Fitzmaurice

I very nearly missed Threads: Two Generations of Painters through Time. I’m so glad I didn’t. The exhibition took place at OpenHand OpenSpace, Reading Sept 01-07, 2020 and featured 27 works by four painters who share connections to the town and each other. I visited on the last day and was pleased to learn it had been well attended despite the impact of the pandemic. Just as all exhibitions, however great or small, first take shape in the mind and after their allotted span return there, this narrative arc is eventually ours too. In this memorial spirit my review aims to provide an account of the exhibition for those who couldn’t visit, and for those who did a chance for further reflection.

Transience is an important theme to articulate and the exhibition venue has a tale to tell too. OpenHand OpenSpace is located within Brock Keep, a Grade II listed building that previously served as barracks and depot to the Royal Berkshire Regiment, and later as a shelter for the homeless. Since the 80s it has provided artists with studios, exhibition space and an education and exhibition programme that is open to all.

The story of Threads started last year with a chance encounter between two of the artists, Caroline Streatfield and Joe Packer. Thirty-three years earlier they had studied together at Berkshire College of Art and Design and both had one parent who painted. As they talked they discovered each had thought about having a joint show with their parent and agreed it would be great to do so together. One benefit of this double-pairing was the extra comparisons it introduced. Not only could visitors reflect on links between parent and offspring, they would be able to compare the different ways personal histories can serve historical and contemporary painting trends.

Joe Packer was born in Battle Hospital which, until it was demolished in 2005, stood on a site close to Brock Keep. After studying Fine Art at Norwich School of Art and the Royal College of Art he has gone on to exhibit widely, including shows with Charlie Smith, London, John Moores 23 at Walker Gallery, Liverpool and most recently Aleph Contemporary, London. In 2018 he was awarded the Contemporary British Painting Prize. His mother, Jennifer Maskell-Packer (1944-2016) was born in Knowl Hill, Berkshire and studied painting at the Berkshire College of Art (1960-64). During a lifetime dedicated to the visual arts and poetry she exhibited widely with notable London venues including Flowers Gallery and Barbican Centre. In 1992 she appeared in the Arts Council film Behind the Eye which was broadcast on Channel 4.

Caroline Streatfield has lived in Reading since she was eleven years old. Shortlisted for the National Open Art Prize in 2018 and a finalist in the Ingram Purchase Prize in 2019 she was awarded an MA in Painting from the University of Arts, London and became a studio member of OpenHand OpenSpace. Her father, David Streatfield was born in 1943. He was active on the London art scene in the 60s and 70s and continued making art in a variety of media until 1983. Prompted by this exhibition he is painting again after four decades given over to business, international travel, research and consultancy.

As I move around the exhibition I met with numerous faces looking out, gazes from another time and place, yet in the majority of Caroline Streatfield’s paintings figures are viewed from the back or have their faces hidden behind their hands. Only in one painting Souvenir for Millais does the subject meet the viewer’s gaze. Souvenir, from the original French, means an act of remembering and this is undoubtedly a central concern for Streatfield, though fittingly nothing can be taken at face value. Streatfield employs the folk costume as the critic Paul Carey-Kent pointed out “as a metaphor for the communist ideal of utopia” which, given her Slovak heritage, must be recognised as bitterly ironic.

Engaging with her larger-than-life figures I sensed some interesting tensions at play: these strong, assertive women have a monumental presence that made me think of Michelangelo’s sibyls yet they have been realised in a brisk painterly style that is a more akin to Manet and recent portraits by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. A visitor could easily read these figures as portraits of specific ‘real-life’ individuals, yet taken together they reveal themselves as archetypes, personifications of central European narratives wrapped up folk costume to question notions of nostalgia and longing. Streatfield confirms this in a recent statement: “Drawing on themes from the former Czechoslovakia and surrounding countries, my work is an exploration of narratives – whether truthfully told or embellished – [that are] handed down from generation to generation.” It was in identifying and reflecting on these tensions, specifically between pictorial expression and meaning, that I found the most rewarding aspect of her work.

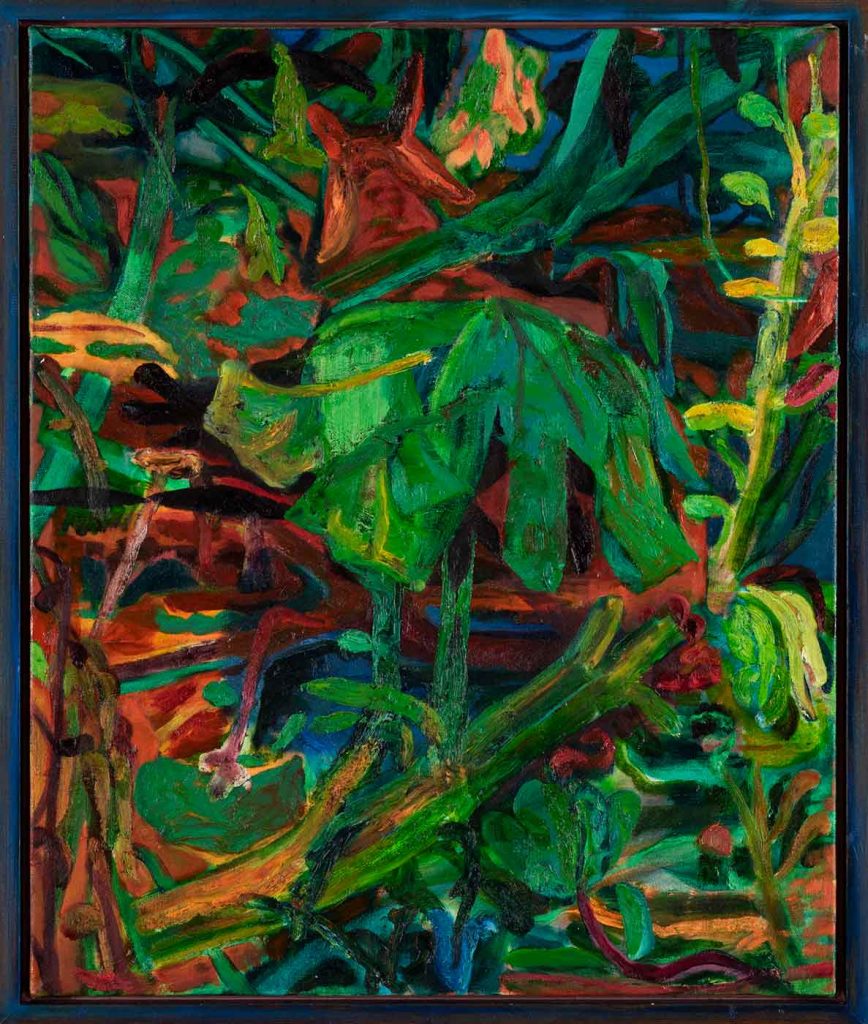

Memory and identity are clearly important to both Joe Packer and Caroline Streatfield but each artist works with them quite differently. Packer’s dense and richly coloured canvases contain motifs that suggest plant forms, especially those that jostle for light in hothouses and informal gardens. Like Streatfield his sources can also be traced back to the natural world, but he recalls and adapts them to serve pictorial rather than symbolic ends. Talking to me about a painting in his studio recently he explained how his paintings develop organically from smaller studies, and how he sometimes has to modify canvas stretchers to accommodate an evolving composition. It struck me this approach, where structure, colour and surface are subject to change over time is well suited to the sense of unruly nature he invokes. Certainly, as with any good painting, to properly experience his work you must draw close and linger. You might find that a typical painting such Duskcluster I might trigger memories, might make you feel like you are a child again peering into foliage. On the other hand you might prefer to connect directly with the painterly qualities, especially the heightened sense of colour and rhythm arrived at through multiple layers of stains, glazes and impasto. Whatever your way in your patience will be rewarded.

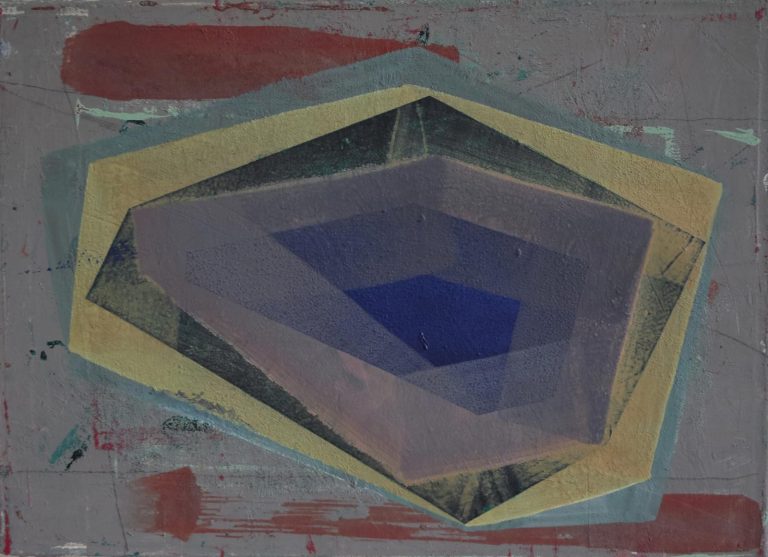

The largest painting in the exhibition at 122 x 183cm is Batavia Harbour 1: Boundaries by David Streatfield. Finished this year the composition is dominated by a striking mix of intersecting rectangles and bold colour that depict two open air stalls in what since 1949 has been called Jakarta. At the right-hand stall three versions of a seated man appear. Lost in thought he is about to open a box of cigarettes. Do the instances suggest he is a regular customer? In front of the other stall a man in a white shirt stands with his back to us and I took this to be a self-portrait. The vendor selling hot drinks meets his gaze. Does the title refer to the customs boundary at the port, or are other boundaries, cultural or personal the subject here? I don’t really mind. Of course one can deepen one’s appreciation of a painting if one understands why it got made but this is an enigmatic work and I’m happy for it to stay that way.

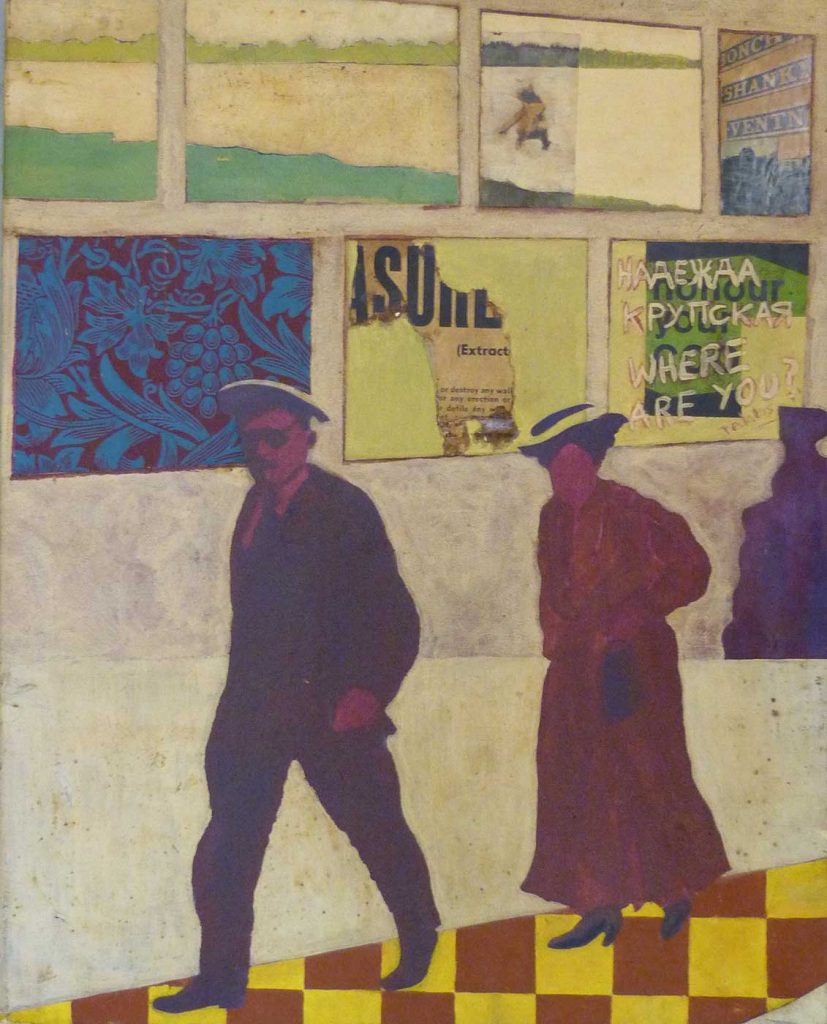

Another much smaller but equally enigmatic painting from 1976 Nadesda Krupskaya: Whereare You? stood out for me as another strong pictorial statement, but again I had no idea about its subject. I later found out Nadesda Krupskaya was a Russian Bolshevik with a passionate belief in education and libraries whose husband was Lenin. Interesting material for sure, but when I visited I was in the dark about that so it could not be the subject that caught my attention. It was the man, staring out at me as as he strides ahead of a featureless woman. To her right another shape that could just be a shadow or a patch on the wall echoes her contours and so seems like a third character in the procession. Further plays between irregularities and straight lines are reinforced by collaged elements. I did wonder whether the wallpaper with grapevine motif was a reference to bourgeois values to contrast with the soviet lifestyle suggested by the other posters. Yet it was an image at the top of the composition I found most powerful. A series of three rectangles (are they posters or windows?) depict a bleak lakeside scene where a solitary youth leaping towards the water is frozen in mid-air. I was intrigued by just how much the composition would be diminished without it. Later, while researching for this review, I found out that Lenin and Krupskaya regretted never having a child. I do not know whether the leaping bather was an intentional reference to what might have been I can’t help but read it as such.

A short distance from Caroline Streatfield’s women stands another. Wearing a wedding dress she faces the viewer but her eyes are closed. From her head a simple but very long veil leads back to a casket containing a doll-like version of her. In the lock of the casket is a key labelled with the words Virginia Clemm. The title of this remarkable painting by Jennifer Maskell-Packer is The bride of Edgar Allen Poe and the clear sense of foreboding it evokes was confirmed through later research. The bride, Virginia Clemm, was only 13 when she married the famous author and was to die of tuberculosis eleven years later. The crisp, delineated forms and raking light reminded me of works by the Quattrocento painter Masaccio but transferred to a psychic realm, some hinterland of dreams. The elegiac tone continues elsewhere. In Oblivious of the yews sad sighing a bride stands alone surrounded by greenery and crows, and in Who will call the swifts now she lies under the hill? A few strokes of white and red paint describe a (deceased) figure dwarfed by an ominous dark mound.

To engage with these sensitive paintings by Maskell-Packer one must enter a realm where transience and loss prevails and the tales are not always of other people. In the The five young people of Napier Road a single lamp illuminates the faces of five children around a dinner table. All wear paper party hats and as one child reaches out to a plate of fish the boys look out with a range of cheeky expressions. There is tenderness and warmth in the scene, but two of the boys are holding poppies and their older sister looks rather preoccupied. Joe has since explained the older sister is his grandmother and the boys with the poppies her brothers who both died in WW1. Knowing this explains the visual impact I had originally felt, and on looking at the painting again, the solemn metaphor of the moths flitting around the light.

These threads I’ve discussed fall into three main groups: those that suggest the influence of the parent, those that depend upon an understanding of art history and those made by the carefully considered way the exhibition was hung. In the first group both Streatfields combine personal memories with historical narratives in compositions where the gaze between viewer and subject is frequently denied. In contrast I sensed Joe Packer has responded to his mother’s poetic and often tragic vision of the figure in landscape by choosing to going ‘inside nature’ in order to celebrate all it has to offer the painter in terms of colour, form and interval. This decision has the effect of shifting the viewer away from empathetic engagement with narrative towards active looking, with the viewer relating to the artwork on their own terms. As an example of the second group I know Caroline Streatfield visited the Prado last year and came back fired-up by 17th century Spanish painting, especially Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez. His portraits of the Infantas, many of whom died as children, were later to prove an inspiration to Millais who also created child portraits as symbols of transience. Likewise one his paintings Souvenir to Velázquez was the basis for Caroline Streatfield’s painting Souvenir for Millais. Joe Packer knows his painting history too, with a modernist sensibility clearly evident in his densely faceted spaces, intense colour and attention to surface. The third group relating to connections made by the hang. It’s is difficult to summarise the experience of moving around the show as the relationships made between colour, imagery and scale acted in concert, however suffice to say I thought the pairing of The Bride of Edgar Allen Poe by Maskell-Packer with The Lament by Caroline Streatfield worked really well, and the placing of Joe Packer’s paintings to counter to the human narratives, in particular his Nashgumbrooke III, very effective.

I’d like to conclude by underlining the aim of this review has been to share my impressions of the show as I experienced it, yet wherever I felt it was of benefit I have included background info uncovered by later research or conversations. All the paintings discussed are my personal selection, nevertheless it was necessary to leave out many other paintings of great interest. If you would like to go deeper please consider connecting with them via one of the links below.

I will remember Threads as an exhibition of relationships between family, friendship and art that together speak of the human condition – or, dare I say it – life’s rich tapestry.

© Robert Fitzmaurice, September 2020

Links:

Caroline Streatfield

Joe Packer

OpenHand OpenSpace

Robert Fitzmaurice