Ruth Calland: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month November 2021: Ruth Calland, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

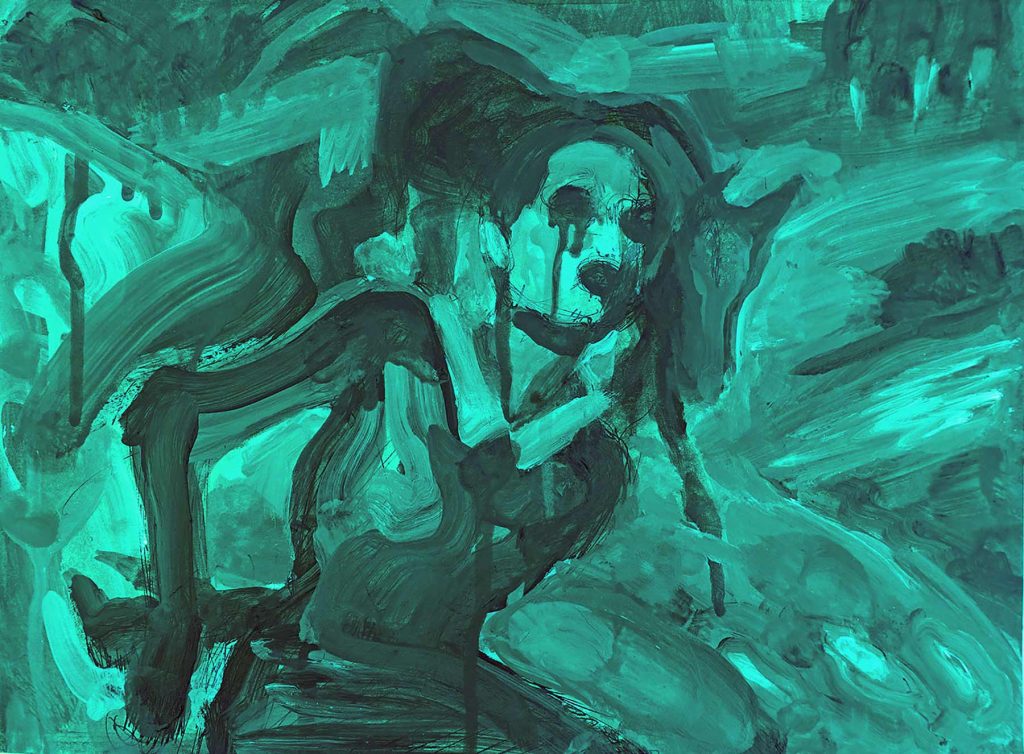

This month CBP talks with Ruth Calland on her curated group show Darkness at Noon on at the APT gallery in London and about her practice in general, its psychological charge and exploration of Jungian themes. Also presented are a new series of enigmatic green hued works, pitched somewhere between a dream story board and reimagined film stills on the cutting room floor.

Contemporary British Painting: Can you introduce ‘Darkness at Noon’, the panel discussion, exhibition, and its themes of alchemy, opposing states and transformation in connection with your own painting and research.

Ruth Calland: Yes, there is a strong connection between the Darkness at Noon project I’m curating for CBP at the APT Gallery this November, and my ongoing preoccupation with conflictual states, a divided self, and transformation. The subtitle for the project is Nigredo of a Pandemic: the dark murky phase of falling apart, paralysis, and closeness to failure/death that the alchemists called nigredo seems such an apt analogy for this strange and dislocated time that we are living through. It’s also a stage of the creative process that most painters would recognise.

James Elkins’ book What Painting Is elaborates on the relevance of alchemical transformation to painters in particular, and speaks lyrically and quite romantically on the physical properties of paint and what it can do as a medium, and the emotional investment in the medium itself by the artist. I relate to that idea, the projection of self into the process, and am also quite animistic in my approach to materials; at its best painting feels like a collaboration between me and the stuff I’m moving around: I like the feeling that I’m facilitating the paint rather than completely controlling it. And I think that’s why I have made so many paintings blind, or partially blind, it’s a way of allowing things to happen that will surprise me.

CBP: You discuss in your own statement your inspiration from the Jungian theme of Coniunctio; a union of opposites and the birth of new possibilities. You talk about it as a clash of opposites, which implies something tempestuous and in conflict. Can you talk about this in relation to the sensibilities of your own painting which can appear graceful and seductive yet volatile?

RC: There’s a distinction between the conflictual process itself, and then the truce which arrives when a painting reaches a point of completion, and this question applies particularly to the blind paintings that I’ve made over a number of years. Someone asked me how I know when a painting is finished, and I think there is an element of recognising that some new thing has arrived, that I couldn’t have anticipated. And deciding if it’s viable or is just a break between bouts. But if it is viable, there’s a small window of time to fiddle with one or two things only, as if the painting is alive and is settling into itself, needing the cord to be cut between us. But now that I’m mostly working with my eyes open, which I’ve had to train myself to do again, it’s a different matter. I have a plan of the kind of mood that I want, and the elements that will probably go into the painting, and then it’s a calmer process of experimentation with my source materials to achieve an approximation of what I was thinking of, plus at some point the arrival of something I wasn’t expecting, which enlivens everything.

CBP: You have previously talked about the notion of blind painting, not looking directly at the canvas, which indicates your strategy of liberating imagination, creating more fluid and suggestive imagery. Can you discuss this technique in relation to things on the periphery, both in the psyche and physically on the periphery of vision? Do visual elements in your studio space like other paintings and marks on the wall infiltrate a painting you are working on?

RC: I agree, it does create more fluidity and the images appear to be in a process of both assembling and dismantling. Those paintings are made in a state of heightened focus, because I’m hunting down a way of bringing divergent things into relationship. Typically I will be using two entities, often two objects I’ve chosen, that operate as identifiers for complementary states of mind, or the two ends of a binary, such as altruism/narcissism or male/female. I often place the representative objects either side of me, observing and then closing my eyes, identifying in my mind and feelings with first one, then the other, as I paint them both into a single emergent motif. Naturally there is a lot of painting over, I often lose things that I like, but I control the colour, type of brush, consistency of paint.

Your question about the periphery makes me think about what it is that acts as a catalyst to start to carry the process forward, into something that is more than itself, more than what I set out to do, more than a preconceived set of ideas, or even emotional nuance needing expression. I suppose that there is no firm boundary between what is ‘me’ and what is ‘not me’. There is a whole swathe of things that come in sideways, either in the ways you suggest, or associatively, in the mind. It might be a memory of something disturbing in the news and how I felt about it, or an experience of seeing a film, or an expression I saw on someone’s face, which would all be part of what constitutes my psychic contents, but simultaneously not me, part of the external world. Allowing space for these infiltrations is a way of keeping things from going flat, it keeps things fresh and moves things forwards.

CBP: You have previously been involved in performance and you discuss your painting process with an intensity of mindset which implies a level of performativity in the making of the work. Can you discuss the notion of performance in your painting?

RC: My actual live performance period lasted for about ten years, and I called the whole series The Epiphaninnies. I was playing with the idea of psychic connection with another person, what that could enlighten, and how it could create an energy which could focus me into a painting or drawing, which I would make blindfold. The costumes were elaborate and people were promised fabulous revelations from their ancestors, or an object speaking to them in their mind, or help from the wisdom of the sea. It was always playful, and I enjoyed involving other artists as glamorous assistants and collaborators. But at heart there was an intense connection with another person going on; some people were very moved by what happened in those situations. In my blind studio paintings I have created a process that is similarly ritualised in it’s methodology, although it’s always unpredictable in it’s end results, just as the live performances were.

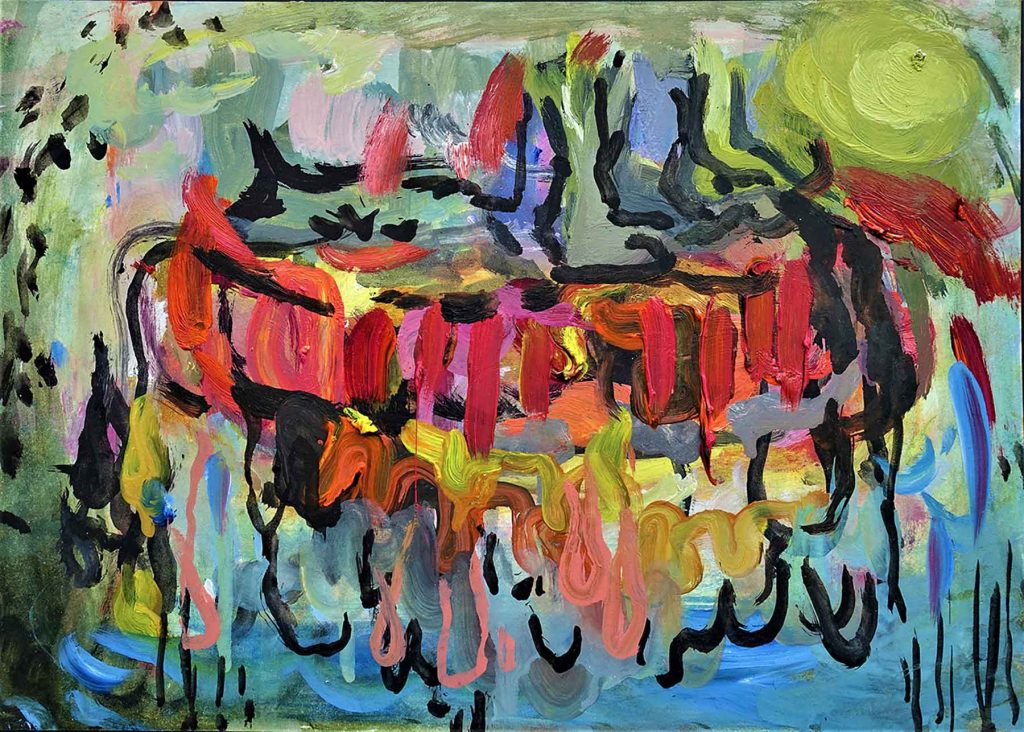

CBP: Imagery from nature and landscape often appears in your work and you curated a landscape themed show, Archipelago: Islands of the Wetlands in 2019. Nature can also imply something feral, a particular tonal sensibility of your paintings. Can you talk about the theme of ‘nature’ in your work in terms of inner and outer experiences?

RC: Yes, the Archipelago project was important to me, in finding a way to work in the landscape, and overcoming my initial feelings of being overawed. Things that feel flimsy or insignificant on site come into their own when you get back to the studio. It seems almost magical that they hold both the experience of a human looking, and some trace or impression of what you were looking at. It’s about what you select and how you see it, as much as what’s there. Projection comes into it for sure, but you’re inviting something in; you have to be receptive, but also develop a way to see which is a meeting of your projections/expression and the external world. I could say I’m seeing into scenery from different sources, and looking for the point where this meets my internal scene. Horses bucking in a field, having been bitten by a vampire, is one example of a scene from a film that appeals to me at the moment. And how that can be translated into painting – it might be through a sort of bucking movement with the brush, or the brush having the precision of teeth biting down. More likely, both combined.

CBP: In contrast to your landscape works, where are the figures in your paintings that look like demons and sometimes references from art history, conjured up from?

RC: Demonic is a good word. I think that comes from my ongoing work with traumatised people, as a Jungian analyst, and from my own experiences of course. Whether it’s the trauma of having to fit around narcissistic others, or a society that marginalises and dehumanises you because of your identity/ies, or disturbing events, we understand trauma so much better now. The typical response of dissociation, fragmenting or dismembering the self in order to fit round a situation where it’s not safe to be yourself, is fascinating to me. The ability to survive and to later come back to things and process them, or reconjure them; it’s often like the myth of Osiris, finding the buried pieces that have been scattered all over the world. In my current work, I’m exploring the psychology of generalised anxiety, a defence against knowing that we are angry about what has happened to us. So I think that might be why the paintings are calmer but still tense: I want them to feel haunted by something hidden within every mark.

CBP: Do you work from drawings or preparatory imagery? What’s the relationship between research material and improvisation in your canvases?

RC: For a long time the work has been about immediacy, so a lot of research but not much preparatory work. Now that I’m working on landscape-based ‘scenes’ there is a lot more point to that, and I am really enjoying the feeling of going into a painting with some things already worked out, or taking a break to do a study, to help with the main piece. It’s quite a novelty to be following a process which is more methodical and it takes away some of the anxiety, but not the buzz. The improvisational space still emerges from where things are being combined in the work, a seam to be mined in an area of unknown possibility. So I could be combining into one painting a scene from a film, a figure from another film, landscape studies I’ve made, a found photograph, or photos I’ve taken myself. I’m finding it intoxicating, and still full of unexpected turns.

CBP: There is a sense of urgency, sometimes desperation in the appearance of fluidity and speed to get the final act down on a finished painting. Are your paintings, or their final layer, completed in one take, or do you return to, fine tune, and sometimes fiddle with them? Do you paint at different speeds?

RC: I do work at different speeds, and also at different levels of intensity. There is the urgency and focus into the centre that I poured into the single motif blind work while painting, and then stepping back and looking at them, breathing more slowly, reflecting, and then a re-entry into that nervous energy. At the moment I am using a different kind of energy, it contains the focus of the previous work, but because I am depicting a spatial scene, a landscape, a ‘gestalt’ that is itself a container, it’s more outward looking, more expansive. So the act of painting is slower and more about a deftness of touch that I’m after, less of a whirlwind – although I will still use the fast, blind method if things seem too predictable, when I need to bring in a catalyst to open things up again.

CBP: How has the Pandemic experience affected your work and studio practice and what is your current studio routine?

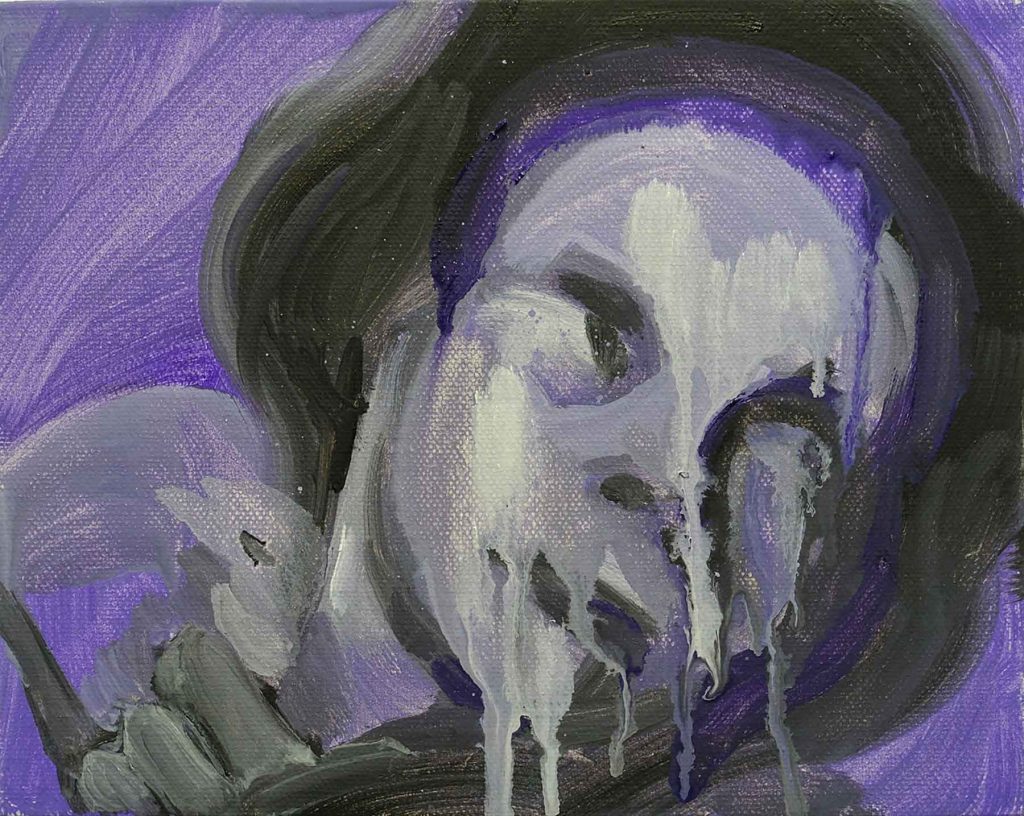

RC: I’m using my bike to get to the studio at the moment, partly due to the petrol shortage, but also because I need a way to stay fit now that I’m not rushing about on the tube so often! The pandemic came at a time when my work was already in the middle of a transition: I’d been moving away from painting with my eyes closed, and had just done a small piece with my eyes open for a show at Transition. I’d made an image of Scarlett Johansson playing an alien who hunts humans for food for her own species, in the film Under the Skin. In the scene she is in a forest, taking off her disguise, a white human skin, and her true alien nature is being revealed. I found it very beautiful. At the PV, everyone was touching elbows instead of hugging, which felt surreal, and the first lockdown started later that month. The whole sense of both alienation and union in the face of anxiety that ensued, was as uncanny as the film scene I’d painted. As time went by in lockdown I realised that I wanted to continue to explore this atmosphere using other filmic references, such as Nosferatu. It was made in 1922 just after the Spanish flu epidemic, and the way that the whole landscape is haunted by a fear of disease is really emphasised by the monochrome colour tinting, especially green, which in alchemical psychology signifies dissolution of the individual ego. I’m painting in oils directly onto unprimed paper now, and gluing it – like a skin – onto stretched canvas. A shift of surface often helps new things to emerge.

Ruth Calland lives and paints in London, completed her MA at Chelsea School of Art, and is a Jungian analyst. Selected for the New Contemporaries and twice for the Marmite Prize for Painting, she is a prize-winner of the CGP London Annual Open, and has shown widely including at Transition Gallery, Studio 1.1, Three Colts, L-13, Flowers Gallery, and in CBP shows in China, Poland, Norwich and London. Her painting and curating practice has extended into multi-media live painting performances in collaboration with other artists and musicians, in conjunction with Folkestone Triennial, Hastings Museum and Art Gallery, Vestry House Museum and others. She has been a Boise Scholar, and won a Fellowship in Painting at GLOSCAT, Cheltenham. Ruth has taught widely at British art schools including Wimbledon, Coventry and Chelsea, and at the Camden Arts Centre. She is a recipient of grants from The Arts Council, The Henry Moore Foundation, and the London Borough of Culture 2019, amongst others.

Darkness at Noon at the APT Gallery, London 4 – 14 November 2021