Plausible Objects / Difficult Things

Iain Andrews • G.L. Brierley • Pen Dalton • Tim Dodds • Sam Douglas • Alex Hanna • Alison Pilkington • Joanna Whittle • Frances Woodley

Essay by Dr. Frances Woodley, author and curator

‘. . . although objects typically arrest a poet’s attention, and although the object was asked to join philosophy’s dance, things may still lurk in the shadows of the ballroom and continue to lurk there after the subject and object have done their thing, long after the party is over.’ Bill Brown.1

An arrangement of objects, nameable and useful with which, or to which, we do things, is a common enough point of departure for a painting. Some painters represented in this exhibition follow this traditional approach, that is, rematerialising objects into painted worlds of things. In the past this was often confined to the genre of still life. Other painters included here generate such worlds from materiality alone, using process to elicit ambiguous things that are nearly or barely recognisable. The only reliable objects in these painted worlds of things are the paintings themselves (albeit as mere digital reproductions in this virtual exhibition), their supports made of wood, canvas, copper or paper to which paint, mediums and varnishes are made to adhere and mix. This essay considers how things take shape in painting, how recognisable objects of our world become plausible things when transformed through paint, and how, as Martin Heidegger points out, ‘something else adheres’ to make them both difficult and affective.2

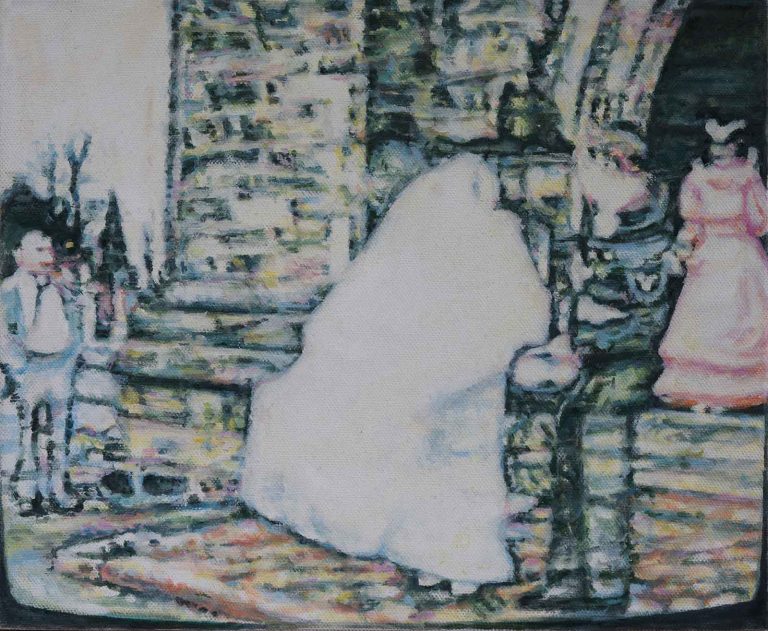

Objects challenge the painter. Tim Dodds writes: ‘I’m stubborn about working from direct observation. . . . There’s a sense of satisfaction when a painting is finished in that it articulates that encounter in some way. In this sense, the capturing of the thing in the finished painting could be seen as a return to the object.’ Immediately, and importantly for this essay, the time and space of painting can be seen to prise open the differences between objects and things. The first, nameable and recognisable, the other not so, but instead reliant entirely for its impact on the mediation of the medium and the associations brought to it by the viewer. Joanna Whittle seeks out familiar objects to paint that were once full with expectation such as tents, flagpoles and follies. Captured initially in observational studies, they are then sabotaged by imagination and temporal inconsistencies, liquidity and light, scale and space. Instead of what they were in life they become highly suggestible things in painting. In another painter’s practice, a cluster of trinkets, objects of no consequence, lead Alex Hanna on a different sort of journey – to Velasquez: ‘I felt this world emerge as I assembled the small group of porcelain characters . . . I started to imagine the assembly within Velasquez’s painting, Las Meninas.’ For Hanna, ubiquitous ornaments become stand-ins for Velasquez’s Infanta and courtiers, thereby assisting their migration from nameable objects to unnameable and unstable painted things. It is a journey from solid to viscous in which identities are liquified.

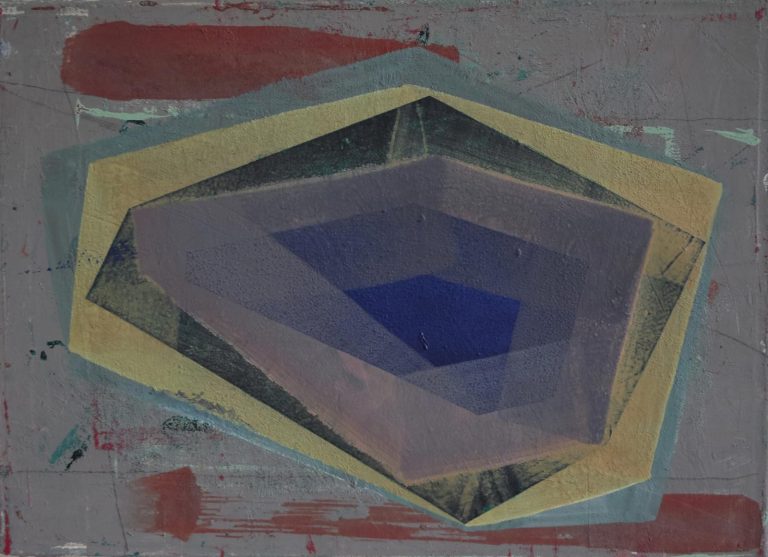

What, then, makes for a thing in painting, full with plausibility and potential, yet neither familiar nor describable in the way an object might be? A thing, writes Bill Brown, is ‘temporalised as the before and after of the object . . . thingness amounts to a latency (the not yet formed or the not yet formable) and to an excess (what remains physically or metaphorically irreducible to objects)’.3 Thingness, for Brown, is ‘something not quite apprehended’. It is this that characterises the paintings of G.L. Brierley. ‘When I pour the paint onto the surface I work until a feeling of light, shadow and pattern come together to (usually accidently) make a space.’ Here, then, space itself emerges as a thing. ‘The process involves balancing margins, organic and mechanical, recognisable and unrecognisable, animate and inanimate, skill and dumbness.’ Things in painting, we are reminded, also embrace the overlooked – the cavities, creases, gaps, in-between bits, the obscured and partially revealed. We see this in Alison Pilkington’s painted ‘hollows, dark spaces in which indistinct and ambiguous things lurk, partially visible or invisible.

Plausibility, of course, goes beyond the immediate believability of objective representation. Plausibility is secured by a thing attaching itself to slippery memory, past sensations, yearning and desire. We want to believe in things. This has some credence in psychology’s Rorschach blot and Roger Caillois’ reverie on the markings in stones.4 Plausibility in painting is earned not by attempting to name or categorise things but by the visceral, phenomenological and psychological responses they elicit, and our succumbing to their agency and affectiveness. This can be seen in the paintings of Whittle and Sam Douglas who stretch plausibility in their play with unstable temporal contexts. Whittle writes: ‘Each painting has a basis in reality but it is built up from many sources containing elements which contradict each other and ultimately undermine the reality of the scenes.’ In similar vein, Douglas writes about disrupting ‘faithfulness’ with, what he refers to as, ‘disruptive scratches, grittiness, wrinkles and other elements’ that play against the initial motif to remind the viewer of the objectness of the painting’.

The thing is, painting is difficult, as is looking at paintings. The things in a painting can be difficult too. Take Pen Dalton’s Egregious Painting for example. To her surprise, I have taken her ‘recursive’ motifs (a term adopted by her from Rosalind Krauss’ understanding of medium specificity), to be things in painting. They are a mixture of neatly cut shapes, sugar-sweet impasto blobs and inky drips. Reminiscent of both barricade tape and sweet wrappers, her paper cutouts assume a plausible volume due to the illusion created by their attached shadows and vibrating colours. However, the coexistence of actual volume (the impasto blobs) with the illusion of depth means that while Dalton is able to bolster their plausibility with shadow, she is also able to undermine the illusion with materiality. Though plausible within the logic of her paintings, her painted things are intentionally indefinable so as to evade meaning. Iain Andrews also writes of the ‘object-ness of the marks’, in this case where the addition of an applied shadow can make a mark operate independently of its representational function.

Andrews, a therapist as well as a painter, writes: ‘I don’t know to what extent the forms prove difficult for the viewer. If painting does its job, then I think the trauma of the source material in some way becomes transformed or adjusted through the process of making a work’. For this painter, difficulty is both embraced and displaced by attaching his primary sources to art historical images. His The Eat Me, for instance, is based on a previous painting of his, The Giant Sigismund, itself based on a study by Titian.

Another feature of the paintings here are the compositional devices employed: the suggestion of precarity or gravity, opacity or translucence, entropy or fluidity, as well as the formal arrangement of elements such as discreteness or clustering and the ambiguous treatment of distance and depth. These devices serve to create visual and visceral entrapment for the viewer. They pose an intentional difficulty in settling the subject of a painting, keeping it in play. Ewa Lajer-Burcharth, in her inspired critique of Fragonard’s The Island of Love (1768-70), explores this in terms of equivalence: ‘”foliage” of hair’, ‘dark-green spongy-form molds limned by light’ and ‘foaming vegetation’. In a passage that speaks to the pareidolia of Brierley’s Katabasis series, Lajer-Burcharth writes of ‘a jet of water that is a silver-white mound of nothing that marks the liquified centre of this composition . . . The whole space buckles under the weight of the bizarre, cavernous mass of the hedges, so suggestive that they, rather than anything else, seem to constitute the very subject of its representation’.5 Yet there are no actual hedges here, nor waterfalls. It is only the materiality of paint that suggests such things. In the paintings of things, rather than the representation of objects, formlessness (material, compositional and contextual as explored together by Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss) suspends artist and viewer alike in a state of uncertainty.6 Given time however, aporia clears and things come into view. Intended and unintended pareidolia takes hold though we remain uncertain of what exactly it is that we see. Brierley, Whittle and Douglas use such ploys to keep ambiguity in play. In Brierley’s paintings it is their unknowability, in Whittle’s, their impassability and in Douglas’, their confusion brought on by crepuscular light.

What emerges in this exhibition is that the plausibility of things in painting requires the mediation of ‘deep materiality’, the artist’s inventiveness in harnessing it and the viewer’s willingness to believe in it.7 Lajer-Burcharth explains this deep materiality in lucid terms when discussing Chardin’s painting as ‘the simultaneous reward and revenge deposited on the canvas, a texture of ambivalence’, a deep materiality that, she argues, ‘produces its own discourse in terms of reciprocity between the subject of a painting and the paint itself’.8 She writes of it ‘as a material register that must be examined as a domain of meaning’.9 James Elkins, on the other hand, describes materiality in painting as a process of ‘coagulating, cohabiting, macerating and reverberating’, evoking it in alchemical terms as a ‘sludge’ that becomes ‘a hard scab clinging to the canvas’.10 Working like the proverbial alchemist, Brierley transmutes pigment and medium into unknown and unknowable manifestations and habitats. Such a practice emerges out of play and process and the artist’s intimate experience of the consistency, shrinkage, texture and translucence of her materials. Pen Dalton refers to materiality too, albeit in more objective terms, when she writes: ‘My job as a painter is to attend to what I am doing now . . . and allow [paint] to do what paint wants to do: drip, spill or congeal – dribble, wrinkle, flow, splat.’ In contrast, in the hands of Whittle, deep materiality has the potential not only to evoke stuff and matter but also speculative narrative as can be seen in her painting Memorial Postcard. ‘Paint mimics mud, sticky and motile, whilst canvas hangs in stillness under skeins of white paint, mud splattered with washy dishwater turps.’ There is, I suggest, a magical abjection at work here, the simultaneous transformation of before and after. In Dodds’ recent paintings this material equivalence goes so far as to blur the boundary between his abject constructions – made of ubiquitous, broken and recycled materials – and their representation in painting where model and painting have become one and the same thing.

There isn’t a painter here for whom viscosity and liquidity isn’t key to the representation or manifestation of things in painting. The leaking, draining and weeping of paint inhibits illusion and makes things difficult. Physical wrinkling, welling and sagging, wring out every association with aging skin and the skin of things leading, perhaps, to feelings of melancholy. However, it is worth pointing out that the paintings in this exhibition tend to keep outright abjection at bay, the drips and dregs being otherwise too readily associated with tears, collapse, rot and ruin. Instead, viscosity, that balance between solidity and liquidity, form and formlessness, is tended to by the painter so that the ‘liveliness’ so valued by Isabelle Graw is retained.11 It is ‘control versus accident’ as Brierley asserts. Stiffness, viscosity and fluidity thus emerge as requiring more than the mixing, manipulation and masceration of paint and medium to be affective. In this regard, Hanna writes about the importance of brushes, how their shape, size and capacity play a part in the volume and consistency, resistance and flow of paint on support. In his Infanta and Dwarfs 1 the final ‘marks’ applied are hair-like tendrils that, having hung in the balance as the paintbrush was lifted, were then deftly flopped to entangle the thing entropically in its own background. But a mark can just as easily create a visual impediment as happens in Alison Pilkington’s use of black strokes to create a ‘space or state that is just out of reach’.

Many of the paintings included here rely on the creation of a theatrical space whether a serendipitous clearing in the paint itself, the suggestion of a studio tabletop or even a model theatre for their performance of things. Andrews affirms this when he writes: ‘The idea of creating a stage or space within which to improvise and play is particularly important to me.’ Brierley takes this notion of theatre even further so that ‘the ‘things’ exist in a contained environment, a scene that plays as much a part pictorially as the objects within’. Hanna writes of the performative nature of paint, how it is able to ‘throw up light catching touches . . . creating some of its own tones and colours’. Douglas points out that a painting’s materiality, its palimpsestic qualities and surface reflection, implicate the viewer in its performance as it reveals itself from different angles. Andrews also understands materiality itself as a sort of viscous performance, full of potential: the ‘messiness and physicality of the incarnation’ and ‘participation in sloppy, physical events, the birth of my children for example, that straddle both the spiritual and physical [are] redolent of the ‘gloopiness’ of paint”, not to be avoided, but holding within it ‘that physical mess that teeters on the brink of becoming, without having fully become.’ It is in these ‘theatres’ of becoming that painted things come into their own in painting.

In all these paintings, time and temporality are of the essence. Time, a measurable dimension, accounts for time taken on microscopic technique or the time of day depicted in a painting that contributes to its plausibility. Time is also time taken. Douglas revisits his paintings over lengthy periods of time during which their atmosphere is coaxed from ‘an accretion of mistakes, [and] alterations’. Temporality, on the other hand, is time experienced subjectively and phenomenologically as conflated, stretched, still, incongruous or ambiguous. We see temporality at work in Whittle’s paintings: ‘Time moves through paintings at different rates . . . yet there is evidence of current or recent activity with lights lit or tent openings pulled tight.’ Light can thus be seen here as the inseparable partner of temporality in painting. Whether fictional or observed, eked out or leaked out, suffused or effused, caught or suppressed, painted light creates contexts for the apprehension of things. And, with light comes shadow. Pilkington’s glowing sunsets often cast no shadows at all making her painted things feel curiously weightless and her ‘hollows’ depthless while Dodds’ recent sulphurous palette elicits association with the exaggerated lighting effects of horror films. All plausible. All difficult things in their own way.

Afterword

Now here’s the thing. How far might I be allowed to stretch the notion of the painting of things? Is paint even necessary or can things and their materialities be coaxed from a screen? To many, digital painting’s origins and deference to traditional painting render it abject (in the sense of inferior to, or lower than). Yet Photoshop is now commonly used by contemporary painters, whether as preparation or in combination, though it is still often dismissed in terms of what Heidegger refers to as a ‘mere tool’.12 But should it be considered more than this? Digital materiality is illusory rather than tactile, its virtual textures fashioned in light and pixels, its medium odourless, sterile and stable. Furthermore, digital painting is not applied directly to a physical support, this only coming into play when the image is printed. But the question I pose here is whether these characteristics are sufficient reason to disqualify it from belonging to what Isabelle Graw refers to as painting’s already ‘highly differentiated language’.13 Should painting aim to become a more interconnective practice, as Carl Robinson suggests, embracing the digital as it has done with photography and various forms of collage?14 It is in the spirit of this enquiry that I conclude by offering my own paintings of things. In doing so I am making the point that it is useful to remind ourselves that paint is only one of the definitions of a medium. As Carol Armstrong argues in her essay ‘Painting Photography Painting’, ‘no medium is singular or autonomous’ and that ‘by definition mediums are go-betweens’.15

The sources for artists’ quotations can be found in the texts on the individual artist’s pages which are made up of edited extracts from the correspondence I had with the artists in preparation for this essay.

1. Brown, Bill, ‘Thing Theory’ in Things, Brown, Bill, (ed.), Chicago UP, 2004. p.3.

2. Heidegger, Martin, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’ in Basic Writings, Heidegger, Martin, Harper. 2008. p.146.

3. Bill Brown, ‘Thing Theory’ in Things. p.5.

4. Caillois, Roger, Barbara Bray (trans.), The Writing of Stones, Virginia UP, 1970.

5. Lajer-Burcharth, The Painter’s Touch, Princeton UP, 2018. pp.191 & 199.

6. Bois, Yve-Alain and Krauss, Rosalind E., Formless: A User’s Guide, MIT, 1999.

7. Lajer-Burcharth, Ewa, ‘Materiality and Subjectivity: Response to Isabelle Graw’ in Lajer-Burcharth, Ewa, Chardin Material, Sternberg, 2011. pp.59-60.

8. Ibid. pp.32-33

9. Ibid. p.90

10. Elkins, James, What Painting Is, Routledge 1999. p.45.

11. Graw, Isabelle, ‘The Value of Liveliness’ in Graw, Isabelle and Ewa Lajer Burcharth (eds.), Painting Beyond Itself: The Medium in the Post-modern Condition, Sternberg, 2016. pp.79-101.

12. Heidegger, Martin, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’. p.146.

13. Graw Isabelle, ‘The Value of Liveliness’ in Painting Beyond Itself: The Medium in the Post-Medium Condition. pp.93-4.

14. Robinson, Carl (ed.), PhotographyDigitalPhotography: Expanding Medium Interconnectivity in Contemporary Visual Arts Practices, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2020. pp.167-188.

15. Armstrong, Carol, ‘Painting, Photography Painting: Timelines and Medium Specificities’ in Painting Beyond Itself: The Medium in the Post-Medium Condition. pp.123-124.