Artist of the Month May 2024:

Angelina May Davis, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

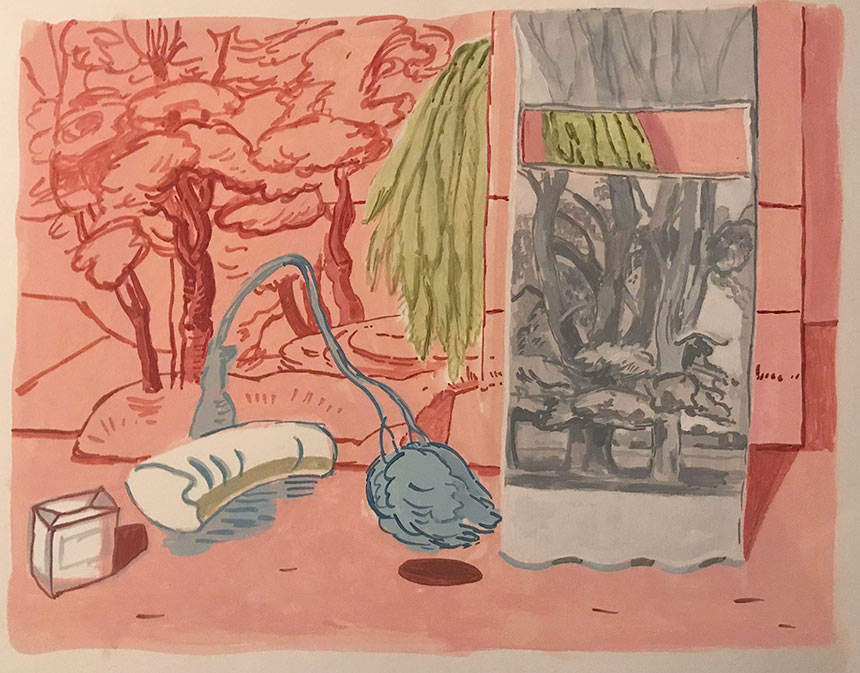

Studio 2024

Studio detail 2024

Angelina May Davis’s paintings are fabrications, plundering imagery from childhood TV and art his-tory. She is interested in thinking about the past and what shapes us, using the transformative act of painting to reflect on history and culture as well as her own sense of belonging.

Davis revists the rural English landscape of the 1970s, restoring the English elm as depicted in re-membered films, archival footage and English landscape painting, as metaphor for loss and long-ing, recalling a nostalgic and insincere past. Her paintings are claustrophobic worlds in which there is ambiguity, artifice and the possibility of things just out of view…

At odds with the political unrest of the 1970s Davis’ landscapes are seemingly benign, perhaps de-picturing an idea of Englishness, that can have uncomfortable associations within contemporary British life. Real, remembered or imagined, a closer look at Davis’ landscapes reveals nods to a burgeoning class consciousness and the collapse of modernity.

CBP: Your main body of work in recent years is the Restoration series, depictions of pieced together landscapes, like stage sets, with a distorted sense of dreamy nostalgia. Can you introduce this series?

AD: Around 2016 I was beginning to think about landscape, firstly in relation to my Swiss heritage and the Alpine landscapes that my grandmother grew up in. I was fascinated by mountains (I have a fear of heights) and was exploring a relationship between archival images of the place that she lived in Switzerland sourced from 2nd hand bookshops, and objects that I had collected over a number of years that all related to the act of looking, recording and capturing memory. I was also thinking about belonging and identity and realised that my own sense of belonging was tied to growing up in a rural village and the surrounding landscape. So there was a kind of seamless transition between looking at Alpine landscapes and returning to the village where I grew up to begin to draw and record a sense of place that I felt intimately familiar with. I quickly realised however that the landscape surrounding my childhood village was and still is fairly inaccessible. A backdrop or mis en scene. A place belonging to someone else. Which led me to consider land ownership and English history. Staging the landscapes, bringing them back into my studio and fabricating them from multiple sources provided the settings in which to ruminate about my relationship with Englishness and with the past.

CBP: You talk about memory and loss, symbolised by the depiction of the English Elm in your work, and the contradictory complexities of heritage. Were your ideas for the series in place before you started the body of work, or did they evolve on the journey of making them, alongside cultural developments, like rethinking museum histories?

AD: The English Elm and its associations for me really developed as the body of work grew. I was collecting images of English rural landscapes in old books, from archive film footage and the paintings of Gainsborough, Constable, Stubbs amongst others, and the shape of the elm was particularly distinctive. I remembered it vaguely in the landscape when I was a child before it was completely devastated by Dutch elm disease and disappeared from the English hedgerow. Its figure of 8 silhouette was something I recalled from illustrations in books about trees when I was growing up. I felt there was a certain irony post-Brexit, in restoring the shape to the landscapes in my paintings, borrowing from different sources, from art history as well as popular culture, at a time when there was a kind of rallying call by politicians to make Britain great again, tapping into a collective nostalgia. It seemed insincere and manipulative. And it felt as though we were being asked to un-remember some of the shameful aspects of our history. I thought this diseased tree (which I sometimes painted blue) was a motif that could represent loss as well as a constructed and insincere view of the past. And the nostalgia generated through colour was a facade that could reveal that insincerity. As I made the work I also thought about class, the tension between the attitudes of conservative middle England and the working life of a village; the idyl that we are pedaled and my own experience of living on a 1970’s housing estate at the edge of a village. I use paintings to think about my values and how these were formed. I didn’t set out with research in place, I used the process of making paintings to research and the series evolved. I have become absorbed by the idea of the English village, my ambivalence towards it and a feeling of longing that I still have in relation to my rural upbringing. This is the subject of the work I am currently making and has involved visiting selected locations, identified from the old travel books, funded in part by a grant from AN that I was awarded last year.

CBP: You love collecting I think, tactile archival memorabilia. Can you talk about how this source material influences your work?

AD: I have been collecting things since I was about 8. My studio is full of stuff, and I enjoy finding multiples of a specific object, so I have loads of old slide viewers and picture viewers, flashbulbs, tape recorders and reel to reels as well as piles of books. I love obsolete technology and its packaging. I enjoy going to the science museum and finding some of the things that they have in their displays that I also have! I like painting objects and often they bring a certain whimsical or comic book humour to the paintings, as they stand in for figures and relationships form. They allow for a certain playfulness through anthropomorphism which taps into my love of cartoons. Objects have been the focus of my attention and my paintings for many years, so it feels quite natural to me that they should litter the landscapes that I am painting as they litter my studio floor. They bring the landscape back into the studio.

CBP: Is the book series a direct reference to the archive source material inspiring your painting? The idea of museum displays feels like a narrative within your work. Can you discuss this aspect, in relation to the book series and in your work more broadly?

AD: I began the books almost by accident. I was wondering if there was a book on a shelf in one of the cottages that I was painting that somehow represented an idea of history what it might look like, and I painted a green book with a small castle on the cover. A simple motif like a cartoon book. Books are a symbol of academia, education and knowledge, but they also represent a particular viewpoint. I had some textbooks that my dad had in school and their representation of Empire was quite shocking. It made me think about how much those schoolbooks had formed his generation and their sense of national identity. My parents had a very modest bookshelf that was aspirational, mainly filled with local history, books about the Royal family, Shakespeare and cookery books. But the books that I paint are vague, enigmatic, the covers often empty or suggestive, props that have left the world that I am painting and materialized in the studio. Fake. Once I began the series, they each became an archetype, and I kept finding new ‘types’ to add to the collection; diaries, dictionaries, prayer books, binders to collect hobbyist magazines into. They were also a simple and self-contained image, not complex like the large works, satisfying abstract blocks of colour to work certain things out formally, that could then inform the larger work and at times find their way back into those paintings. It is also an autobiographical collection and references that modest bookshelf at my parents’ house presented as an archive or set of relics.

CBP: Can you talk about developing dioramas for your paintings? Its like the artist studio itself and creative props are also an interwoven subtext of the work. If models were not created for this current series, I understand they have been made for previous bodies of work, and this in turn has influenced the style of your recent painting?

AD: As a child I made model villages. I have carried on making models of things, cardboard objects, painted decoys and props that make their way in and out of paintings. I don’t tend to work from dioramas although I do sometimes make arrangements of objects to paint from, if I need to see how something sits in a space or how light falls. I love the theatre of dramatic lighting, shadows cast, and the sense of anticipation or apprehension that can be created. But mainly I feel that as a painter, much of what I do happens in my studio through the transformative act of painting and I want that to be referenced in the claustrophobic world that I create, with things just out of view and backdrops that conceal and reveal simultaneously. The studio is often the setting for the landscapes. So you see the gaps and edges, the way they are staged; I am interested in edges, in the locations that I visit, and within the sets of my paintings. They suggest otherness, being on the outside. There is often another shallow space just behind the image, or a sense of something lurking in the wings. I wonder what is just out of view and paint things that I can’t really identify, loitering in the folds of curtains or glimpsed through the gaps.

CBP: When I came to your studio last year, I remember looking at your mixing palette, alongside the distinctive colour schemes of your painting, which are almost purely chromatic, using harmonious and contrasting combinations. I commented on the fact that your paintings feel sculptural, solid and fluid, yet resist using tonal contrast, blacks and whites to achieve this. I thought it was a conscious decision and you said it’s just how you’ve always worked with colour instinctively. Can you talk about this a little more?

AD: I used to be a bit scared of colour and worked in monochrome when I first began to paint. But I have been painting for a long time now and I have learned to trust my instinct and use all of my experience. That said it is often a very painful process at the start. I don’t begin each work in the same way. Every painting is different and sometimes when I look at work that feels resolved I have no idea how it happened and so I can’t recreate things easily. I have synesthesia which means that for as long as I can remember I have seen words, numbers, days of the week, decades as colours. I have a very strong reaction to colours and colour relationships. So when I am painting it is the first thing that needs to fall into place, for me to get a strong feeling from the painting and the place that I am imagining. I am fascinated with how colours can locate things at a point in time and how something can feel very contemporary and then slip into the past. I recognise colours from the past. I was aware from a very young age of the subtle differences in the colour palettes of the cartoons that I watched, and I could tell instantly if I was going to enjoy the programme from the colour palette. I used colour to identify preferences and make choices, I still do. Those colour memories are strong and make their way into my work. In the landscapes that I am painting, increasingly I want colour to sit at a point between lush, seductive and nauseating. To emphasise a tension between nostalgic memory and insincerity, a pantomime version of the landscape.

CBP: You do a lot of plein air drawing in your sketchbook, the style of your drawing sometimes evokes that of early to mid 20th c English landscape drawing like Edward Bauden and Paul Nash. Are you conscious of your reference points and influences whilst you’re drawing from nature?

AD: When I draw it is a very instinctive activity. I am often irritated by the way everything that I do looks like my own work, and I can’t seem to get away from it. I look at other people’s drawings that I admire, and they do things that I can’t. I make very deliberate marks. I work at a certain pace, I see things in a very particular way. And no matter how much I try to disrupt that, in the end I can’t get away from myself. Of course there are people whose work I look at, Graham Sutherland, Samuel Palmer, artists whose work is a lens through which you see familiar places. I love Paul Nash and am aware of Edward Bawden and there is an unmistakable Englishness in their work that if you go into an English country lane and draw the trees carefully you can’t help that there will be a similarity. But it’s not a deliberate reference. I also love Hockney’s lanes and feel incredibly connected to the places that he depicts as though I am remembering them. But I find that the process of drawing is so integral to looking and feeling that the drawings that I make in situ are a way of recalling being there. Not just the appearance of the place. That is why they are so essential to painting. Photographic references only really capture the appearance for me. I need more than that.

Folded final demand, oil on board, 35cm x 28cm, 2022

Green book, oil on board, 29cm x 42cm, 2022

CBP: Can you discuss about the relationship between the sketch book, the gouache works on paper and the canvas paintings as an extension of the drawing process?

AD: If I didn’t draw I couldn’t paint. Drawing is my way into painting. I generate something in drawings that opens up a space to paint. The gestures and marks and the slow looking that takes place all help something to form that I can work with. I often feel that by drawing I can see the paintings. They begin to appear in my mind’s eye. Sometimes they form a structure into which other things can be placed. The small gouache paintings are a more intimate way to generate images and often follow a period of drawing. They can also be a catalyst for larger works. I enjoy changes in scale. Making large paintings is inconvenient. They stack up in your studio and take a lot of time to complete. But in the end, I am always seduced by the experience of having my whole field of vision filled with an image as I paint, and the challenge of trying to get a complex and disparate set of elements to work at that scale. When I stand in front of an image and walk up and down, painting it, I feel as though I am in the space, and I suppose that’s what I want the viewer to feel.

CBP: Are you ok to talk about the personal fight in your paintings, the make or break, trying to create the alchemy?

AD: I hate the start of a large painting! And if I love what I have done initially I know it’s probably going nowhere. I rarely make something that isn’t a reaction to a disastrous start! I don’t make ‘cool’ paintings, I struggle and get frustrated and then suddenly something will happen (usually to do with colour as I have said previously) and it’s as though the painting has materialised and come to life in front of me. I am probably describing what many painters go through but it’s a mysterious, precarious, exhilarating and addictive process. I often say that I have a terrible anxiety that my current painting is the last good thing I will ever produce. I genuinely feel like I have no idea if I can pull it off again! I have never watched myself painting. I don’t really know how I do it. So it feels risky, stepping into the unknown.

CBP: Finally, going back to childhood; you talk about your early memories like watching tv as being part of the influence on your work. Do you drift and transport back to this place whilst painting?

AD: I think it has more to do with the relationship I had with the TV when I was young. A feeling that a whole world was contained inside a box, a black and white or Technicolor or cartoon world (my family TV was a big old Granada rental). Painting feels similar in the way that the images are just the bit that you can see. There is a whole world in painting, off the edges, in the distance, behind every object. And you can easily switch between those different colour states in a painting and conjure up things that can only exist within the painted world. You are looking in on something and that feels very similar to how I felt about TV. When I am painting, I am definitely transported somewhere. I stop thinking in words and just think through the act of painting. But I don’t consciously find myself thinking about that childhood place. When I stop painting, I am back in the room.

Angelina May Davis is a painter currently working in Birmingham Artspace, in an industrial build-ing in Aston. After graduating with a degree in Fine Art Painting in 1988 from Coventry Lanchester Polytechnic she exhibited at Ikon Gallery, Lanchester Gallery, Leicester City Gallery and MAC amongst other spaces before completing an MFA at UCE in 1998 Throughout those years she was involved in setting up and running various collaborative artist studios in Birmingham. Raising a fami-ly from 1997 she moved her practice to the dining table for 10 years before beginning to make large paintings again in a studio from 2007. In 2020 she began the Turps Banana Correspondance Course, completing 2 years. She had 2 large paintings included in Bloomberg New Contemporaries 2021 and Blue Elms was acquired by the Government Art Collection. She reached the 2nd round of John Moores in 2020, was shortlisted for the Jacksons Painting Prize in 2020 and 2021, and her large scale water colour ‘Pond’ was selected by Juliette Losq for the Outstanding Water Colour Prize in 2021. She is represented by Division of Labour.

https://www.angelinamaydavis.co.uk

Interview with Faye Nicholson: https://www.salomesalmacis.com/angelina-may-davis.html