Natural Abstraction

Essay by Katrina Blannin to accompany the Slippery and Amorphous Exhibition

“For the painter, the codes and languages of painting, like the paint itself, are, by their very nature, slippery and amorphous.”

If ‘all the world’s a stage’ then the stage is all the world – our world. While you are watching dancers, whether Nureyev, Astaire & Rogers or The Jackson 5, you are longing for an effortless performance: a seamless integration of impossible postures, perfect balancing acts and exquisite gesture; spot on timing. You don’t want to see the painful struggle or the hours of arduous practice in those moments: you are there to see the art not the toil – you are there to be coerced, or bewitched, through a perfect choreography of codes and signifiers into a kind of state of wonderment, horror or desire.

But there is a paradox here of course. We know that these human-being performers are fallible and not automatons. And we could also say that the dance performance is actually saturated with both the life experience of the performers as well as the creative labour or work activity of the performers (and this includes the work of the director/choreographer). So although our own previous encounters with, and knowledge and participation of the art-form is perhaps more limited and much less developed, surely, the dance in all its aspects of expression and technical dexterity, physical wit and rhythmic precision, is actually mirroring or at the very least referring to our own human experience? And is it the same with painting? You could say that painting is at the very least a somatic activity that we have all taken part in at some point in our lives – even if only in school. Through all sorts of life-work experiences we have accumulated a whole range of optical and physical taxonomies of colour, texture, shape, gesture, posture, decoration and design to one degree or another – it’s there whether we actively choose to think about it or not. The whole process is one of reflexivity. As Brian Muller wrote in the exhibition catalogue for the exhibition he curated Real Art ‘A New Modernism’: British Reflexive Painters in the 1990s, dance or painting can be sites of creation where ‘…it [reflexivity] refers to content being shifted to firmly within the viewer’s own cognitive process, in which the viewer watches himself/herself, watching himself/herself looking.’ 1 Mick Finch, writing about Torie Begg one of the artists in the exhibition, substantiates: ‘At the heart of Begg’s and Muller’s texts is a claim that her paintings shift the sense of reception of the work entirely into the field of the viewer. They describe the paintings as producing a material object with no illusionistic residues referring exclusively to the relationships of its own process. This though is done not to present the viewer with a process puzzle to solve but to construct an ‘active viewer’ who checks imaginary associations of what the painting might be against the material fact of the work’.2

We are watching the dancers: perhaps The Temptations or maybe ballerina swans spinning on the spot in unison and smiling with ease. We are now looking into the painting as if we are looking into the mirror and experiencing the haptic through materiality, the physical sensations of gesture and performance through memory and perhaps even the aesthetics of form through knowledge or education. The central relationship: the seesaw of creator and viewer is both empirical and intellectual. The invited participant will absolutely sense the pain, joy and intensity of the performance: she will observe, detect, tingle. We know that each next dance move, every brush stroke or rational calculation could lead to a mistake or a fall so empathetically we are watching ourselves on the knife edge of error and triumph – will they make it…? How can we enjoy and understand the aesthetics of good form and dramatic expression, as a viewer, when we can’t already ‘know’ ourselves something of the backdrop of ‘toil’ and trouble involved: the search to find the right ‘arrangement’ and the desire to accomplish the perfect move or gesture through endless testing and practice? The imperative is to be able to recognise some of the physiological and psychological aspects of the journey: to be able to perceive some of the fear of failure or the fragile nature of creation in order to then buy into the possibilities of success.

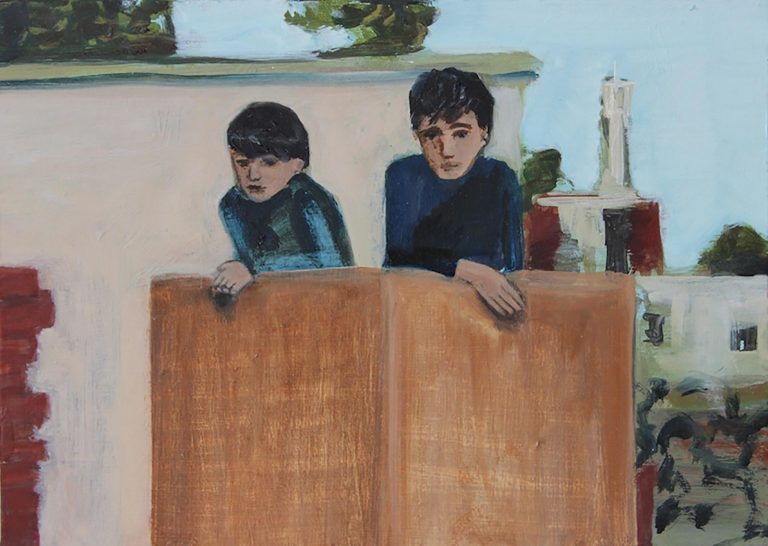

The painters in Slippery & Amorphous present a very natural, human kind of abstraction. The ‘purity’ of Greenbergian formalism and its self-defining inward looking stance seems a long time ago and now in a post-Richter, post-post-conceptual era we are looking at a hybridity of isms cherry picked with ease from the history of painting going as far back as the beginning of Modernism in the latter half of the 19th century and further.

The eclecticism of painting today means that you might see a Nabi type sketchbook drawing done in Day-Glo alongside the flourish of accents in an Auerbach, or a Max Ernst frottage in amongst some new imagined apocalyptic landscape. In non-representational work you might see the embrace of a kind of rococo excess: rolls and rolls of paint all piled up, or at the other end the minimalist’s approach of reducing it all right down – or as one painter put it ‘emptying it all out’. You will see a foray into the depiction of geometric volumetric solids, or perhaps the repetition of wallpaper design patterning, played off with gesture and freestyle graphic line. You might see the human figure distorted, reversed and recalibrated, and in reference to still- life I have seen a banana painted a hundred times or some meat created out of paint: very thick paint in the right meaty colours sculpted to physically resemble a kebab. Surface, materiality, figure-field interplay, breadth and depth, construction and space, Rymanesque object-hood, expressionism (as in auto-biographical), poetry (where someone’s poem serves to provide the idea or emotion) or socio-political investigation (current affairs or historical events), as well as different approaches to direct study-like observation and quotation (whether using photographs, famous paintings, some sort of tableau or actually going ‘plein- air’), are all possibilities in a melting pot of what painters may rather casually refer to as a ‘painterly language’.

Today, on the one hand concerns about the appropriation of styles, or even narrative content, have been put to one side; no one wants to close the floodgates. On the other hand painters are deliberately and eagerly re-visiting and re-configuring Modernist tropes, and anything before it, without the same self-conscious hang-ups and ‘death of painting’ gloom; the self- criticism and irony often found in and around the activity of painting during the 1980s and 1990s. Today painting is unashamedly about painting; it is what it is. In Slippery & Amorphous both the activity itself; what seems to be a very ‘natural abstraction’, and the imagery that ensues or the final physical material realisations of that activity, are indeed hard to pin down and put into words, and yet, paradoxically, we as either viewers or those artists wielding the brush are operating in an area that is ‘known’ to us. Just as colour cannot exist without light it is this visual engagement in the visual activity – whether dance or painting (and where the author is both absent physically but also present in the artwork) – that evokes and inspires.

Katrina Blannin, 2016

1. Real Art-A New Modernism-British Reflexive Painters in the 1990s (published by Southampton City Art Gallery/Leeds Museum) 1996 by Brian Muller

2. Apparently Real: Torie Begg’s paintings by Mick Finch 1996: http://www.mickfinch.com