A Moral Life: Place and Memory – The Work of Narbi Price

Written by Nicholas Usherwood

Narbi Price was the winner of the 2017 Contemporary British Painting Prize. This essay, by writer and critic Nicholas Usherwood, has been written to accompany his solo exhibition ‘All I start will end’ at the Herrick Gallery (26 – 30 March 2019). The essay and the exhibition form part of the prize.

“Such [transcendent] symbols are with all of us everywhere and at all times; not only in the language and imagery of our cultural making, but in every most ordinary moment, every least scrap of the world around us, in the rhythms of our own body and in the lights and airs that fill the sky…”

Theodore Roszak: Where the Wasteland Ends: Politics and Transcendence in Post-Industrial Society

Despite the all too obvious signs of its imminent breakdown, we are still living within a secularised myth of progress, one that our urban-industrial society has encouraged us to believe in ever since the Enlightenment, one where the idea that the arts, all the arts, can still reach out for symbols of the transcendent vision of our place within this world, the sacred within us if you like, has come to seem essentially fanciful and quixotic. As William Blake saw only too clearly some two centuries ago, we have, since Newton, been living within a ‘single vision’ world, a scientific ‘map’ of a materialist/theoretical reality – useful for the sake of acquiring power-knowledge – but a world that really bears no relation to the sensual reality of the world as we experience it both for ourselves and through artists and poets; those figures who, as Theodore Roszak movingly observes, “…really look at the world – and look at it, and look at until they lovingly gaze it into their art; no explaining, no theorising, no generalising, no analysing… only the pure pleasure of seeing (or hearing or smelling or feeling).”

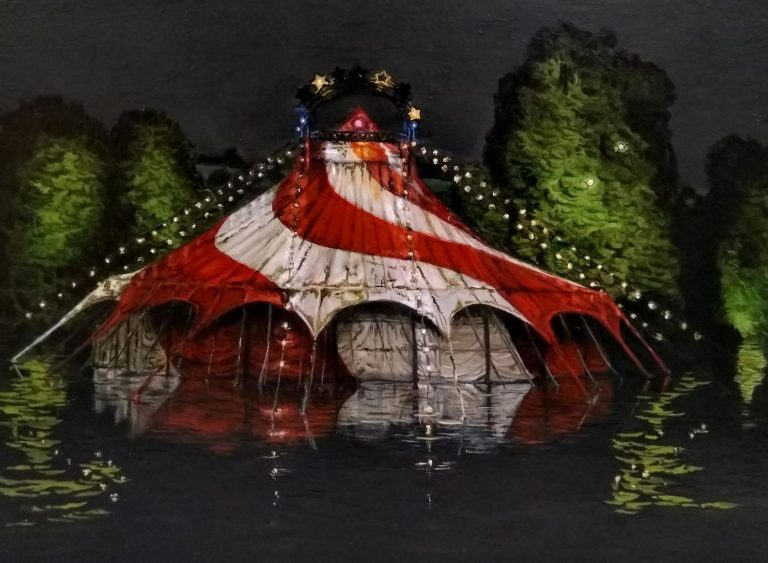

All of this seems to me very germane to the subtle, slow-burn visual worlds explored in Narbi Price’s paintings over the last five years or so, urban and landscape scenes of apparent extreme ordinariness – graffiti-ed walls and underpasses, rows of garages, disused shop fronts, stretches of nondescript roads and bus shelters, fenced in woodlands, stagnant pools and dirty rivers, random slabs of concrete, scruffy grassland – framed from the photographs that Price uses to document the places in the first instance but then all painted with such a variety and intensity of marks, such richness of colour and intentionality of structure, that you at once become alert to the fact that something else is going on here, that while he is drawing our attention to the sheer beauty of the ordinary, the urban scene has become something rather more than a fashionable pretext for a bravura display of painterly skills. They are that of course but, then again, something else is, quite unmistakably going on in them. More or less from the moment he emerged as a mature painter, some 10 years or so ago, Price has been absorbed by the idea of giving visual shape to place histories – forgotten places such as in his paintings of the nondescript sites of Jack the Ripper murders (‘Shan’t Quit’) or a stretch of pavement in Venice where public executions used to take place, places of private significance – for example, a cement path where he was once attacked – or, as in his Codeword works for PAPER in Manchester where, in his paintings of two iconic sites where the notorious 1996 IRA Manchester bomb exploded (one of them the exact spot where the van carrying the bomb had been parked), personal histories of a city he had regularly visited as a teenager to the city’s music scene coalesced with an only too well remembered event.

Now, in one of his latest series of paintings, ‘The Ashington Paintings,’ recently exhibited at the Woodhorn Museum (formerly the Woodhorn Colliery Museum in Ashington) Price comes closer to home, to his Newcastle base – Ashington is less than 20 miles north of the city – and attempts something perhaps even more complex, and perhaps even more indeterminate, again. Ashington, as recently as the 80s labelled the largest mining village in the world, now has absolutely nothing of that history left other than can be found in that complex and often troubling term ‘heritage’ – the massive collieries that studded this landscape mostly vanished beneath tarmac, concrete, water or brown/greenfield sites. But nonetheless, most certainly, not quite nothing, for Ashington had, up to 1984, also been the home of one of the most celebrated amateur/non-professional painting groups in 20thC British Art, the Ashington Group, or as they have now more popularly become known, ‘The Pitmen Painters.’ First formed by a group of miners attached to the Workers’ Educational Association (WEA) in 1934, they met every Monday evening to discuss each other’s work and choose a new subject and receive instruction from a lecturer at Armstrong College, Newcastle, Robert Lyon, they had soon attracted the attention and admiration of professional artists, poets and anthropologists of the time, most notably Mass Observation, in the pre-war period. Post-war they were largely forgotten again until the miners’ strike and pit closures of the early 80s brought their remarkable work gradually back under public scrutiny – with a book, a play and public exhibitions.

Price approaches their remarkable legacy with both subtlety and directness – the uniform size of his canvases echo those adopted by the group i.e. as large as could be comfortably tucked under the arm and taken to their meetings but the paintings themselves address a very different concern, the almost complete disappearance of the landscapes and scenes the Ashington Group painters would have known and often painted. The titles very often give the clue – Untitled Bus Stop Painting (The Hole), Untitled Slab Painting (Newbiggin), Untitled Posts Painting (QEII)or simply, Untitled Road Painting (Colliery)– while the paintings themselves put me in mind of the walker and self-styled mytho-geographer, Phil Smith’s remarkable reaction (when re-tracing writer W.G. Sebald’s troubled journey around Suffolk in ‘The Rings of Saturn’) to the landscape around Sizewell and nearby Leiston; “I walk through countryside-as-desert. I sense everywhere the erosion from the landscape of the ordinary lives of extraordinary people. The eternal present of total obliteration.” Price’s achievement, in these intensely resonant and profoundly Romantic paintings is somehow to give back to the urban landscape, however apparently bleak or blank, its sense of lives being led as well as lives that have been led. As Roszak had it in the epigraph to this introduction “Such transcendent symbols are with all of us everywhere and at all times not only in the language and imagery of our cultural making, but in every most ordinary moment, every least scrap of the world around us…”

Narbi Price’s contemporary visions stand comparison with those lines from Wordsworth’s ‘Prelude’ where he observed of himself:

To every natural form, rock, fruit or flower

Even the loose stones that cover the highway,

I gave a moral life: I saw them feel,

Or linked them to some great feeling…

Nicholas Usherwood, November 2018