Simon Carter: The Shapes of Light

Andrew Lambirth considers a recent series of paintings by Simon Carter.

‘Subjects are only starting points. The further I get from the point of departure, the more I can see the painting…’

The theme and viewpoint of this new body of work by Simon Carter, made over the last 16 months, is that of a spectator standing on a beach and looking out to sea. It is a very particular beach and a very particular stretch of sea, because Carter paints the coast he has known all his life, that he has grown up with and loves. Effectively, this comprises seven or so miles of Essex coastline centred on his home town of Frinton-on-Sea. This is his landscape and his mindset, the crucible of his painterly thought and activity. All his new paintings derive from drawings made at different sites around the town: on the marshes, by the beach huts, along the sea wall. But the focus is not on incidental details but on the elements: earth, sea and sky. As he says: ‘In a sense there’s nothing there – but there’s also everything there.’

A single figure features in many of these new paintings, a solitary outline in a depopulated landscape. In fact, the figure is often a silhouette and is based upon the shadow that Carter himself throws on the ground, and it has the same foreshortening of a shadow at certain times of day – rendering Carter’s tall body stockier in shape. Another source for this figure is van Gogh’s On the Road to Tarascon, famously used by Francis Bacon in his van Gogh paintings, and already used by Carter in a painting entitled Van Gogh in Essex. In his life and his paintings, Carter stresses his closeness with his surroundings: ‘myself and the landscape, there’s no separation between us’. The artist paints himself into the landscape, but his figure also stands for the spectator. We are thus encouraged to share the unique role of artist as observer, and to enter the painting. In fact, there are two main groups of pictures here: those in which a figure appears, and those in which the light is the principal presence. But whatever the subject, these paintings, focusing on the threshold of sea and rock where the elements are in flux, are mostly about how sunlight falls on land or water, and the shapes it makes.

The process by which Carter arrives at these paintings is an interesting and complex one. To begin with he makes any number of drawings in front of the motif, in often quite small sketchbooks. He might be drawing with grey oil pastel, pencil or charcoal and perhaps a couple of coloured crayons (blue and yellow). These are tonal studies done very quickly, made instinctively and without too much conscious control, perhaps six or eight in a morning. Each drawing records about 10 minutes of concentrated looking, and each painting may use 40 or 50 of these drawings. Back in the studio, Carter makes other, more schematic drawings on a light-box, tracing over the original studies, formalizing them. The information in the first observational drawings is filtered and simplified in the studio drawings, and the ideas for a painting begin to emerge. As Carter has said: ‘Subjects are only starting points. The further I get from the point of departure, the more I can see the painting.’

There is a crucial gap between the experience of looking at the sea and the making of the painting. Into that gap comes drawing. It is, in effect, a strategy for distancing the two activities – looking at nature and painting – in order that the painted image is not simply a record of things seen, but a statement about the nature of painting and a more general (and distinctly uncalculated) comment about the glories of existence. Yet the essential mystery of the painting act remains: ‘I don’t know exactly what it is that I do in the studio’, he admits frankly.

Once at work on the canvas, the process is one of endless re-working as Carter explores the dialogue between the ostensible subject and the means of expression. As can be seen from even a cursory glance, Carter employs a purposeful and determined painterly attack, but he is also prepared to revise constantly, to change and re-engage. He comments: ‘I think everything in the studio is provisional.’

As he works on a painting, Carter will refer constantly to his drawings, which might include large charcoal studies, pastels and watercolours. The process of transforming the raw material of observation into the gold of the finished painting is the essential business of the studio. ‘I’m not sure I really get to grips with the location drawings’, he writes, ‘unless I have drawn from them in the studio. If I paint too directly from location drawings I think I tend towards too much of an “impression” rather than inventing structures and possibilities.’

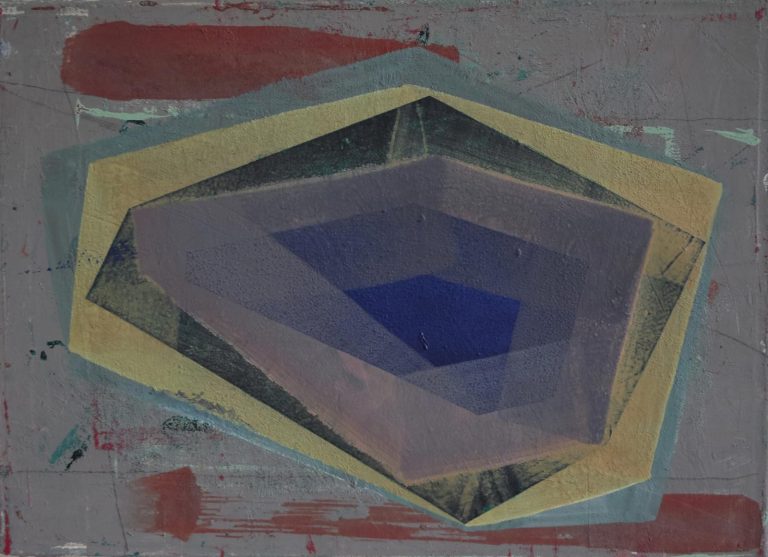

Although not abstract, these are pictures about paint and its formal disposition, the ways in which the orchestration of colour and line can be made to resonate in the human mind and heart. The (still) recognizable subjects give us an entrée into the more mysterious activity of paint and what Carter is doing with it. He does not pursue an obvious realism in his work, but seeks the reality behind appearances – a deeper truth we normally apprehend but dimly, the ‘strange and numinous’, as he says, beyond ‘the familiar assumptions’.

In the finished painting, there are occasionally visible marks of squaring up. Carter does not begin a painting by squaring up a drawing to transfer to the canvas (such a procedure would be far too constraining for him – his activity on the canvas is essentially paint-led), but occasionally he does apply a scaffolding later in the evolution of the image in order to re-locate his subject in the cut-and-thrust of painting and altering. Vestiges of this geometric underpinning may or may not be noticeable in the finished picture, but if present are there because they form an integral part of the image, not because Carter didn’t bother to remove them. For him, the final version of the image which constitutes the painting should include traces of the history of its making, rather as a charcoal drawing retains the ghosts of those sections erased.

Although this may initially appear to be beside the point, Carter is an enthusiastic and skilful gardener, a passion he shares with the celebrated East Anglian artist-plantsmen, John Nash and Cedric Morris. As it was for them, his love of plants and their formal arrangement are activities which feed back into Carter’s painting, both in an understanding of natural processes and in the meaningful disposition of line and colour. Painting and gardening are mutually supportive.

For Carter, colour is remembered but also arbitrary and invented. Quite often the colour verges on the artificial rather than the naturalistic, a painted equivalent to the experience of looking at landscape, with one continuous plane of colour unifying the picture. Pink is a favourite, to complement an atmospheric and varied use of blue. Vibrant orange/red charges across the winter sea or establishes the dynamics of falling rain. Turner lends inspiration to Looking out to Sea, after a visit Carter made to Margate. Previously, he tended to shunt the horizon line out of his paintings, fearing its domination, but now, working with increasing assurance, he is re-introducing it, even in the traditional position on the canvas. His paintings, like all good art, are a mixture of tradition and experiment.

However, the aim is not to be predictable. Carter wants to feel surprise at the painting when he comes into the studio in the morning, and so taking risks is an important aspect of what he does. ‘You learn not to rely on the things that you know’, he says. Much of the thinking occurs in the act of drawing or painting. Carter is not rehearsing preconceptions, but discovering new networks of form and colour to express a view of the world as a whole.

The dynamic movement in these paintings is an exciting part of their appeal, particularly in the two versions of Light on the Sea, Light Breaking and the two versions of Light on the Sea (Easter). The distinctive softly jagged vectors and zigzag lines create space and vitality even though the palette is predominantly mixed greys – made from yellow ochre and ultramarine, for instance. Light Breaking is the exception here, employing a heightened use of colour and a superabundantly charged swirl of line to lasso the viewer’s attention. It is one of the finest paintings in a strong show.

These paintings are all about shapes. In Figure and Yacht II, the yacht’s sail appears above the man’s head, offering an unmistakeable emphasis or accent that has something of the halo about it; also something of the vertical with crossbar which suggests the Crucifixion. Notice also the triangle of absence signifying the sail in Yacht and Rain. The yacht becomes interference in a sea of lines, negative space. The impressive structural logic of Carter’s paintings sometimes seems to lean towards sculpture, and for this body of work one sculpture in particular has been a lasting inspiration. This is David Smith’s Hudson River Landscape (1951), a welded painted steel planar sculpture of great linear inventiveness and elegance in the Whitney Museum, New York.

There’s also a series of 12 smaller square paintings, titled simply with the date of the last drawing from which the painting was made. Carter usually prefers an off-square format, but has settled nicely to the challenge of this more perfect shape. The square presents something to work against when painting landscape (traditionally depicted on a horizontal rectangle), and one characteristic solution sees Carter pinching in the sides of the image, so that it actually isn’t square even if the canvas is. His habit of constantly altering the image and scraping the paint back has resulted in some cases in a build-up of pigment at the right-hand edge of the canvas, but this becomes a valued part of the history (or archaeology) of the painting.

Carter is sometimes called an Expressionist, and his work does in a sense fit within the tradition of German Expressionism exemplified by such artists as Kirchner and Nolde, as well non-Germans such as Soutine and Bomberg. But there is no element in Carter’s work of Expressionist angst: he aims for a distinctly lighter and brighter touch. And his range of reference is far wider than this line of descent might suggest, drawing also upon de Kooning, the Pier + Ocean paintings of Mondrian, and the irreverent celebration of being alive to be found in the work of Roy Oxlade. (He refers to looking at de Kooning’s work as being ‘like opening an encyclopedia – everything you can do is there and you just have to look it up.’) Carter also finds much stimulation in the late pared-down figuration of Peter Kinley, in the long fluid abstract traceries of Brice Marden and the immense seascapes of Alex Katz. An influence closer to home is Paul Nash, and especially the great Dymchurch paintings, lightly referenced in Carter’s Promenade images.

In recent years Carter has worked in close relationship with Constable, East Anglian forbear and master painter of weather and place. He has had two exhibitions in Suffolk of paintings and drawings which explore the older painter’s relevance to his own work (Get Constable at Ipswich Town Hall Galleries in 2008, and Now and Then: Flatford Paintings, at Flatford Mill in 2012), and Constable remains an important presence in his artistic life. But whereas before Constable gave Carter a structure to improvise around, now the inspiration is more to do with atmospheres. Perhaps more important at the moment is a particular painting by Jacob van Ruisdael: An Extensive Landscape with Ruins (probably 1665-75) in the National Gallery. Carter has a photograph of this pinned up in his studio and constantly refers to it.

Also in the studio are orderly shelves of dated sketchbooks, a copy of The Bible, a poetry anthology, a book on Gainsborough, and Seamus Heaney’s The Haw Lantern. A shelf of large art books includes monographs on Braque, Valasquez, Frans Hals, Augustus John, Diebenkorn, Manet, Sisley, Picasso, Delacroix and Vincent by Himself. Carter is eclectic in his tastes and interests, and this represents only a fraction of the art and literature he consults. (Mondrian, Matisse and Patrick Heron, for example, are among the other artists he admires, while an enthusiasm for Munch was rather dampened by the recent Tate exhibition.) He is also deeply interested in that maverick master of English mid-20th century abstraction, Roger Hilton. There is no obvious Hilton influence to be discerned in his work, yet there is a similar nervy sensitivity to Carter’s drawings – a line that stutters enquiringly rather than flows dictatorially. Both are artists who seek to unlock the visual mysteries of the world, rather than impose a vision upon it.

Haiku is another interest, the Japanese lyric verse form of sublime minimalism. The haiku is a three line poem consisting of only 17 syllables, in a strict pattern of 5, 7, 5 syllables per line. The form emerged in the 16th century, reached its peak between the 17th and 19th centuries, and has been much imitated since in the West. Carter is clearly influenced by the succinctness of the haiku and seeks to emulate its precision and compression in his own work. If not quite managing to reduce a drawing to three lines, it’s nevertheless amazing what he can say with a series of more or less freely painted parallel lines over a scumbled ground. In effect what he aims for is a simple set of marks that encompasses everything you see. Small task – vaulting ambition. In these new paintings, Simon Carter has made great progress towards achieving that very laudable aim.

Copyright © Andrew Lambirth November 2012