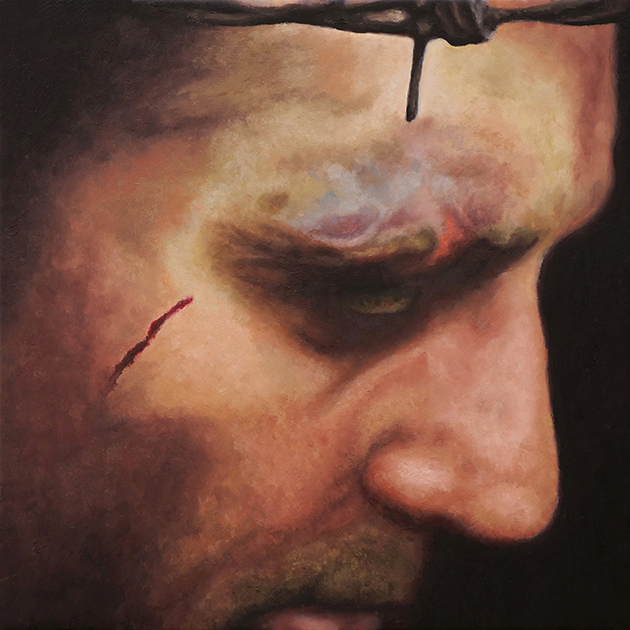

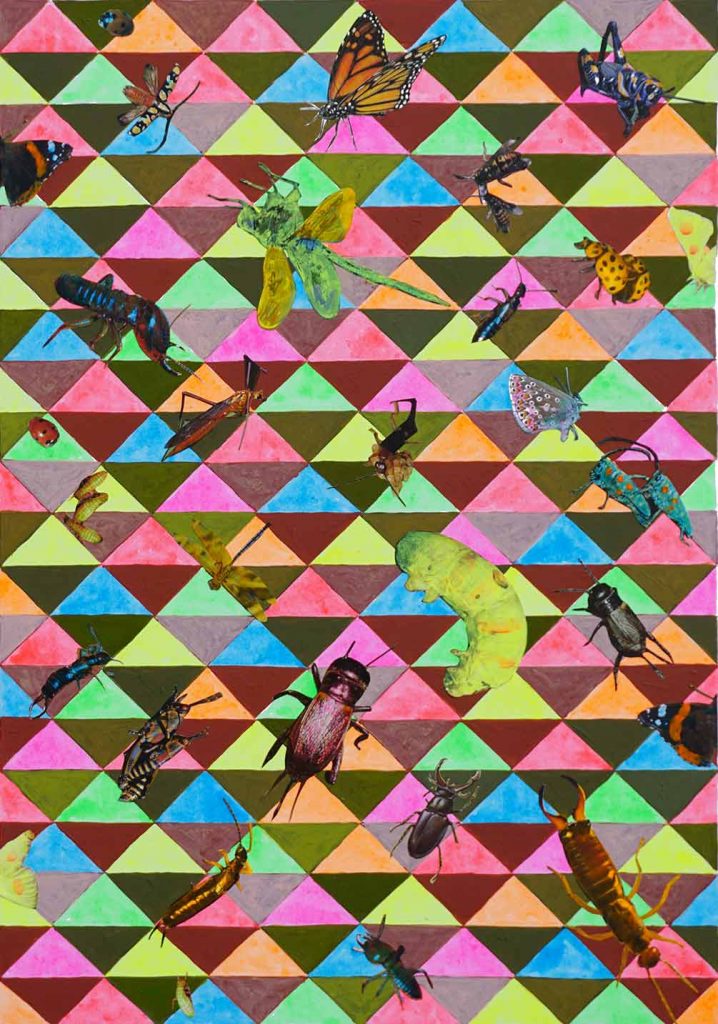

Gideon Pain: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month July 2020: Gideon Pain, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman.

CBP: Eclectic. It feels like you’ve built up a repertoire of imagery, motifs and narratives over time, a career. It’s a challenge to condense that into an artist’s statement – which yours does make sense. I look at your work and feel I understand it, but I can’t pin down a succinct question to ask about it. Could you talk about an aspect of the development of your imagery?

Gideon Pain: I’ve always loved the drama, narrative and theatre that painting lets you explore. The building of something out of nothing by gathering up many separate elements, then slapping them down in a big slam dunk. A viewer’s reaction to this action might be guided but never fully controlled and it’s this fragile, unspoken pact that interests and drives me.

For me building imagery, or populating a painting, is very much like I imagine putting on a play is. It follows a process. This process is made up of tasks which are undertaken, not necessarily in the same order but usually to the same end. They are: Picking a location. This may be a real place or an amalgamation of different locations, merged together in order to stage an event. Some places have many plays in them, others just one and occasionally none. The gut can lead you here, but the pencil lets you explore. Sometimes a place might simply be a stage, a potential filled flat ground with space to fill.

Building a set. Here you populate the space with related things to inform and enhance the main characters. This might be additional objects or simple atmospherics, anything to enrich or capture a mood.

Auditioning a cast. These are the main focus points in the picture. The hook, or more the worm on it, that draws you in until the barb takes hold. These characters appear in odd places, whilst running alone on a fen, browsing in a paper or dozing on a train. They sneak up, introduce themselves and ask for a home. Sometimes it’s in person other times a thing. The set itself might even suggest who it might want to live there, either way they are vital to each other’s being.

Writing the dialogue. This is where you decide how the cast are going to interact with each other and the set. Who is the lead and who the support and what their coming together represents or brings to the scene.

The dress rehearsal. Where you gather everything on stage to see what works and what doesn’t. There is usually a lot of re writing of the dialogue at this point but with a bit of set repainting and some hiring and firing gradually things take shape and a story evolves.

Stage management. Fine tuning all of the different elements toward the most appropriate balance. A point of clarity at best or more commonly a glimmer of comprehension.

The opening night. With hopefully everything in place you send your Frankenstein’s monster out into the world, usually with only a partial notion of who it is or where its bound. Here process and elimination give you the slight reassurance that you’ve tried and rejected many, if not all, of the other bad alternatives along the way. So, cross those fingers and eyes forward.

The reviews. Standing on the side listening out for the echo. The ping of comprehension signalling that something is received, leading to either a contented glow of connection, [a path forward, Hollywood, a seat next to Tom Hanks at the Baftas and the possibility of a billion dollar sequel] or deafening silence and a long walk back to the cold dressing room for wound licking, burning of scripts and starting again.

CBP: Can you talk about the balance between the personal and the political in your work, the interior and exterior worlds that are represented?

GP: Wow that’s a chunky question, but I suppose if I were to take sides, I’d say that it’s 90% personal 10 % political. Seems a shocking thing to write and something I might regret later but the pictures have become more about an internal dialogue and the processing of uncertainties and doubts than a desire to document, change or influence anything. Those doubts are obviously founded within a wider world, and therein have common currency, but I could never put myself forward as any sort of spokesperson or champion.

I studied during a time of miners strikes and political change when the critical realism of artists like Stephen Campbell Ken Currie, Peter Howsen, Sue Coe and Jock McFadyen were being championed as a counterpoint to free market domination and Thatcherite ideals. After college I lived and worked in Dundee where art and artistic practise were very much seen in a wider social context. There was something incredibly romantic, wholesome and invigorating about a sense of purpose and being part of this wider family. The honeymoon passed however, and I started to question my works effectiveness as a solution, and to wonder whether art was being used in these contexts to paper over cracks much better filled with proper investment and long-term vision. I have often felt a great failing in myself for pulling away and not tackling this contradiction head on. At the time however these issues seemed so much better served by more popularist mediums like music, film, TV and literature so I withdrew on a different tangent.

Painting for me is more about dialogue than facts. It’s the journey from one question to the next, rather than any answer or a solution at the start or end of the process. As a medium I find that paint is slow, clumsy, frustratingly hard to focus and direct, perversely though this is the reason I like it. It requires work, pinning down and lots of disappointment but also it gives back freedom and possibility. It’s a balancing act between the head and the gut and although mutually very co dependant, for me, the gut, or instinct, usually edges it.

CBP: You are a member of CBP, you also produce illustrations as well as sculpture and installation. Painting is presumably the core of your practice. Can you discuss how this approach filters into other mediums – if this is a correct analysis?

GP: Painting for me has always been a direct extension of drawing so this is probably the common root that runs through all the processes. It’s all about visualising thoughts or hunches and working stuff out. Some thoughts lend themselves to colour others monochrome. Some notions are flat whereas others need to come out into the world and be walked around. If you start to ride an idea it’s always fun to see where it takes you and the older I get the more I think f*** it lets see where this goes. There’s lots of wastage and doubt along the way but it’s a small price to pay.

Painting and the thought processes it induces are so beautifully adaptable that they can be applied to almost anything. The addition or removal of material, colour, surface, scale, edge, speed, and mark are as fundamental in 2 as in 3 dimensions. I’ve worked as a carpenter/ model maker for 20 years, so I see little distinction between different processes; they are all applicable to a common end and all feed into the mix. This is also true for digital imagery which I use through all stages of making.

The illustration work differs only in that it’s a collaborative process rather than a self-induced, personal one. I enjoy getting out of the studio every now and again and sharing the experience of making an image. Other people’s ideas can be so much better than you own and it’s fun to work things through as a team. Having a brief also takes much of the hair pulling out of your hands, if you excuse the pun, and you can just enjoy the craft. The money also comes in handy as it buys materials to funds other projects.

CBP: Your most recent work is acrylic, though looking on your website you’ve worked in oil. Is the medium relevant to the imagery you work with or is it more an organic, intuitive, what’s to hand approach?

GP: Medium/materials choice has a lot to do with practicality. I mainly work on paper because I like the slick surface, hardness of touch and ease to which images can be cropped and resized. Additionally, it’s incredibly easy to store, both before and after use. Although in the past I have used oil paint I find acrylic is much better suited to this ground. While being fundamentally different materials the addition of extenders, mediums and drying retarders can make them behave in similar ways and produce comparable results. This meant that the transition was not that hard. The advent of acrylic inks in recent years has also added a welcome calligraphic aspect that would have been hard to reproduce with oil paint alone.

Saying this I still use oil paint if drying times are important or if I’m working on anything of scale, just because it’s that much more manageable over large surfaces. Colour might also dictate choice, more specifically how much control is needed between wet and dry appearance. Acrylic still drives me nuts sometimes when trying to get a tight range of tones or hues so I will work on top of acrylic paintings in oil if things are not behaving themselves.

One final although increasingly important consideration in recent years has been the health implications. My studio is adjacent to and in my house so I’ve been trying to limit the amount of fumes and vapours given off when working upon and while pictures dry. Having suffered from contact dermatitis for years I’m very reliant on gloves and barrier creams for skin protection. As a whole I find water based paints much less problematic when it comes to daily usage.

CBP: Can you talk about your daily operation as an artist, balancing studio time, commissions, other commitments?

GP: Balancing is the operative word here. I’ve got a full time job, other than the painting, working as a model maker/technician in the British Museum in London. It eats up the hours but it’s also a rewarding experience, working with fantastic people and having close access to a mind bending variety of artefacts and artworks. I’m based with the exhibitions department who designs, build and install temporary displays in 6 separate galleries. Although busy and occasional fraught the work is seldom dull and can range from moving mummies in the morning to hanging Munch drawings and Manga in the afternoon.

Away from specific objects the span of the collection has also had a huge impact. Zeitgeist takes a spin when seeing 500,000 and 100 years old things side by side. Witnessing how culture is rarely localised but more evenly spread across time and space, as edges merge and ideas are taken up and travel from borders to beliefs, has been a revelation. Something that’s profoundly affected my own practice and influences.

My daily commute to London by train also gives me a couple of hours sitting time to exploit for drawing and planning pictures. I use an iPad, apple pencil and Procreate mainly and find it a really good alternative to sketchbooks. Doing this outside of the studio often helps me to put things in perspective and reinterpret ideas in a fresh light.[ something that also happens when I’m out running, funnily enough] Working in London is also great for access to other museums, galleries and shows. A big payoff with working at the BM is that I get free entry to most other national art institutions. As well as being financially great it also means I’m happy to take a punt on an outside contender. This has led to many happy surprises. Some of these visits are also out of hours, which is a double bonus on popular shows.

Studio time tends to be evenings weekends and holidays. I’m lucky enough to have a set up in my house which makes it very easy to drop in and out of projects, as time allows. I used to rent studio spaces but found the commitments of a young family and making money meant I had little real time to exploit them fully, and frustratingly they became just very expensive storage spaces.

Another plus of working at home is that my kids and their friends have seen art making as a part of normal family life, all be it a frustrating one when dad’s blocking the kitchen table or cluttering up the front room stretching canvases again. Another positive of a home studio is that it’s really easy to think of your work in a domestic rather than gallery context.

If I’m making large pieces or need to work on many things simultaneously I will beg, borrow or rent temporary space to suit. For installations and site specific pieces I’ll try and arrange to do most of the build, or at least a large part of the assembly on site. Often the amount of access available will shape the nature of the finished piece.

Commission work normally gets fitted in around the client and whatever timescale they request. I’ve always found folk very negotiable though. If you’re upfront about clashes and unforeseen delays a compromise can often be met. I also try and take work with a long a lead time as this allows some flexibility to work on different things simultaneously and not loose traction on any one project.

CBP: Is Gideon Pain your birth name, or a professional pseudonym?

GP: No one has ever asked me that before, but I see where you are coming from. No, it’s my real name with a Barnaby thrown in the middle for good measure. My parents , Ann and Michael, wanted to give us names that stood out, hence there is also an Abigail [much more popular now than back in the 60’s] and a Bathsheba in the family. If I was to pick a pseudonym, other Old Testament belters like Zebedee and Ichabod have always been favourites. [Although I wasn’t brave / cruel enough to impose them on my own offspring.]