David Lock: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month August 2020: David Lock, selected and interviewed by Paul Newman.

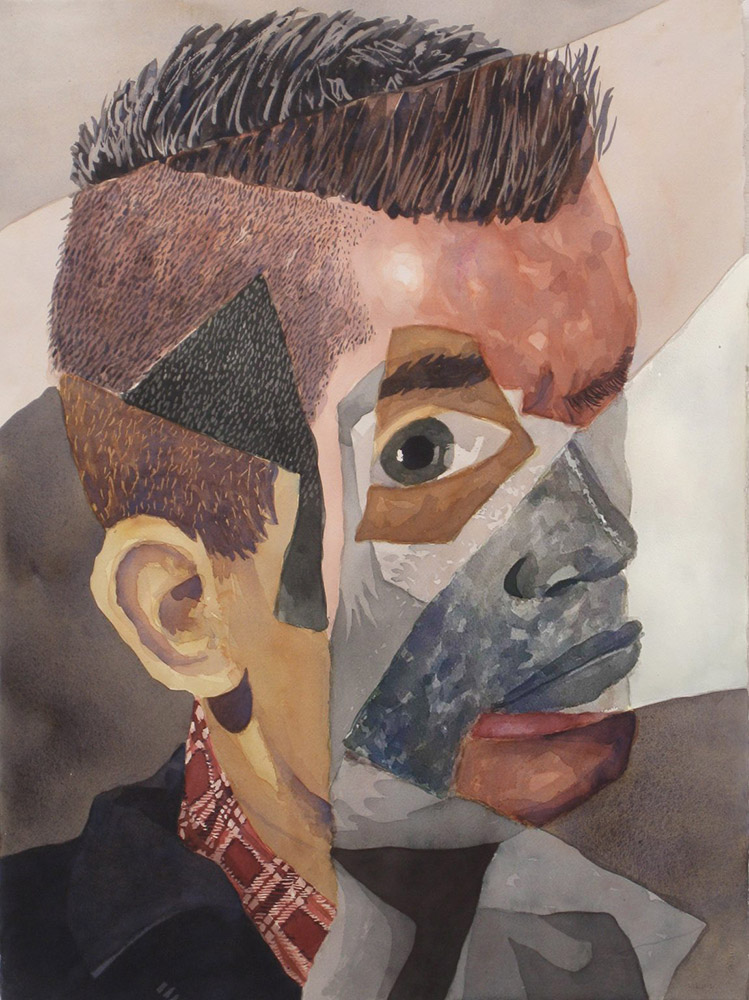

CBP: Collage is key to the construction and narrative of your painting. Your collages and paintings of men have kept the evidence of this construction depicting sliced and patchwork figures. There is a vulnerability and tenderness, even pathos, for example with an ongoing series called the Misfits. You even refer to Frankenstein’s monster in discussion. Can you talk about how the transformative effect of painting helps form the tone and sensibility of the work, compared to the collage, and the difference between the watercolors and the oil & acrylic paintings?

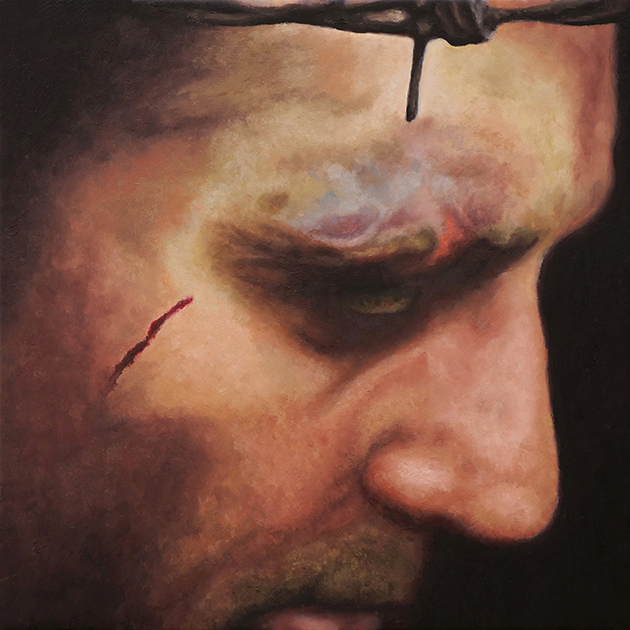

Misfits (interior), oil on linen, 160 x 110 cm, 2020. In ‘between parts undone’ three person show, 2020.

Misfits (Landscape), oil on linen, 160 x 110 cm, 2018. In Telescope, curated by Nigel Cooke, Jerwood Gallery, Hastings, 2019.

David Lock: I guess in answer to that, I came about the collages as a more active way to engage with the images I saw in the magazines and mass media. I used to make a wider body of work encompassing different subjects but I came to just focusing on the collage portraits – the ‘Misfits’. As a stand alone, my collages, to me they feel inert, other people might disagree but I see them as just a means to an end.

To really own it, I need to translate it into painting, slow it right down and rework it. It pulls them away from the magazine aesthetic into another place, the language of painting.

In ‘between parts undone’ three person show, 2020.

I refer to Frankenstein because it’s about construction, reassembling these different body parts, so they are asking questions about what it means to be a man today. Of course the men’s style mags, 10 Men (who I’ve published with), and GQ etc, they are always asking that, but only on a surface level based around consumption and lack, it’s designed to turn the page. You hope with painting to create subjects which work on more levels. That tactileness of painting, it’s sense of touch no other medium can compete. The watercolour’s came about as I wanted to use a medium I could take anywhere. I also like its unforgiving nature. You cannot hide with it. I like making the larger watercolour Misfit portraits as I think the scale and the medium increases their vulnerability somehow. I think that also extends to my large oil paintings but the scale of them is more about the human body. In that way they’re more physically demanding for me to make.

As a gay, disabled man, hegemonic masculinity, i.e. the idealised, heterosexual masculinity is something that i’ve always had to fight against and define myself in relation to. That’s why my misfits are pluralistic and constantly shifting. As fragmented agents of discourse, they are rejecting any idea of a singular ‘ideal’ man.

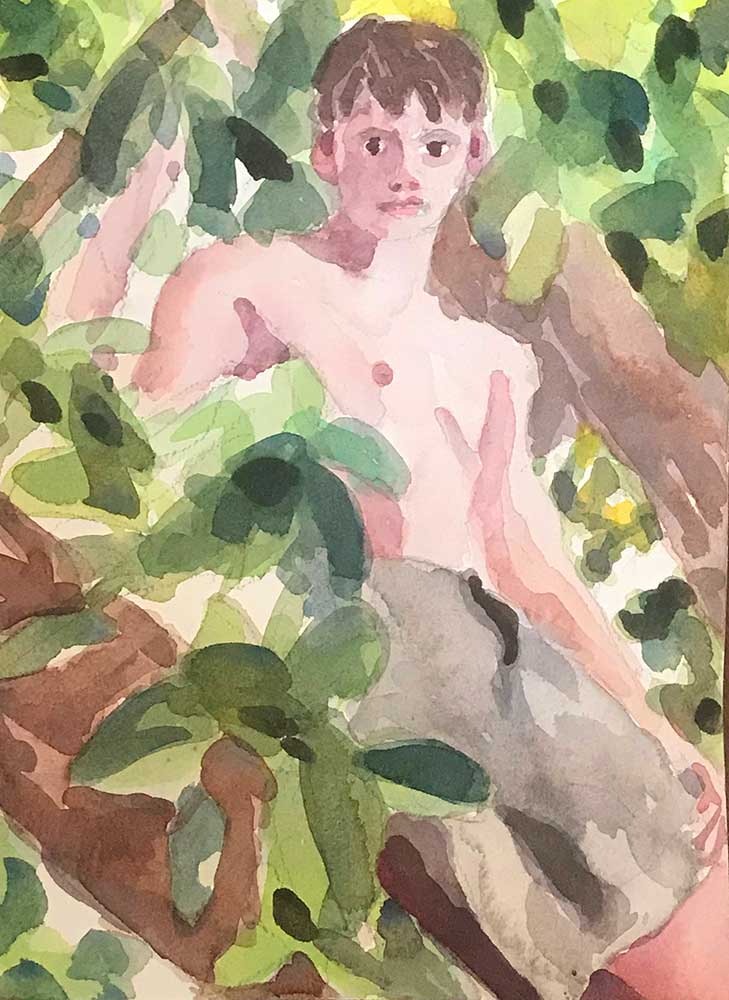

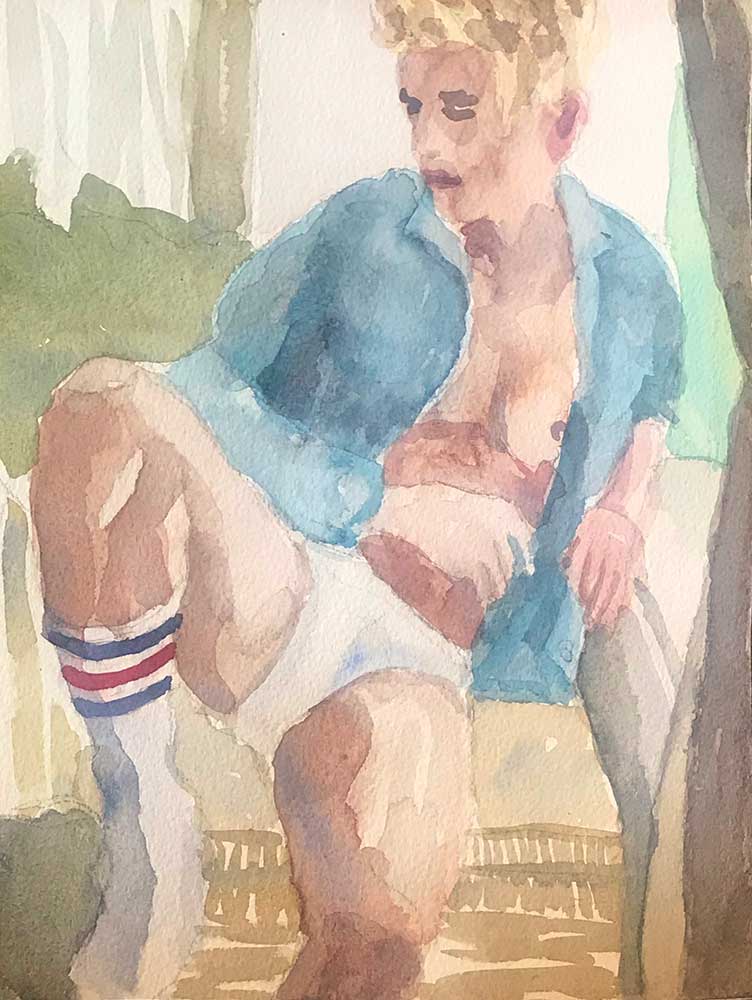

CBP: New studies ‘Lounging’ and ‘Boy in tree’ don’t appear to use and present your signature collaging technique. Are they part of your other series of work that are more singular studies?

DL: Yes they are very much a continuation of those singular studies. These paintings which address portraiture first came about through an exhibition I was in at MOCA, London in 2017 that celebrated the 50th anniversary of the death of my uncle the playwright Joe Orton. For this exhibition I made a painting called ‘Blue Boxers’ which paid homage to the portrait of Joe by Patrick Procktor that hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. In the show, I made three paintings to hang on a wall based collage. Since that show, I have continued making these paintings. With all my work, both the ‘misfits’ and these singular ‘other’ paintings I’m considering how masculinity is socially constructed and culturally configured. Going back to the misfits, the way they aim to destabilise contemporary cultural narratives, I suppose my singular portraits complicate that reading, but life is complicated, and full of contradictions.

With the singular paintings, they are also ciphers for a certain ideological idea of presence, which carry notions of idealism and promise. I’m playing with the partially clothed male body as a locus of homoerotic desire, so they are also about the state of becoming, they are active. If I was only making the singular portraits it wouldn’t sustain me. I like the contradiction it presents with my fragmented misfit paintings. I think it makes my practice broader and richer than just having one or the other.

CBP: ‘Boy in Tree’ utilises the motif of the figure merging into the ground – a garden? You often depict urban garden settings and domestic plants in your painting, that could be a nod to Hockney and sometimes allude to a narrative of a stage set or play. Can you talk about this element in your work?

DL: The images I choose to paint are already out there circulating in contemporary culture as I’m interested in their currency as to what constitutes as sexy or desirable in terms of contemporary masculinities. As all the images I use are appropriated from magazines or the internet I actually find it hard to find the right subject I want to use. It’s an intuitive thing, the image will just pop out at me when with most photos of men in the mass-media i’m not interested, desire works like that. So the ‘Boy in a Tree’, that image was in my studio for a long time, I cannot even remember tearing it from a magazine. Sometimes I crop the image before painting it but usually I leave it as it is. It’s hard to put my finger on it. I do find though, when I choose something to work with every element needs to be right, both the attitude, and the composition.

CBP: You’ve discussed before that the subjects are sourced from magazines and part of a critique of male objectification. Do you ever paint sitters or include fragments of people you know or are close to you in your collages and constructed men?

DL: I’m not averse to using my own photos. I’ve often wanted to bring in some of the people around me. It’s just finding the right moment. In that regard, I love that series Procktor made of his then partner Gervase for his first show in New York in the late 60’s. He was ahead of his time and the show itself was not a success. In addition to that, I also really admire many of Chantal Joffe and Elizabeth Peyton’s paintings of the subjects that are close to them.

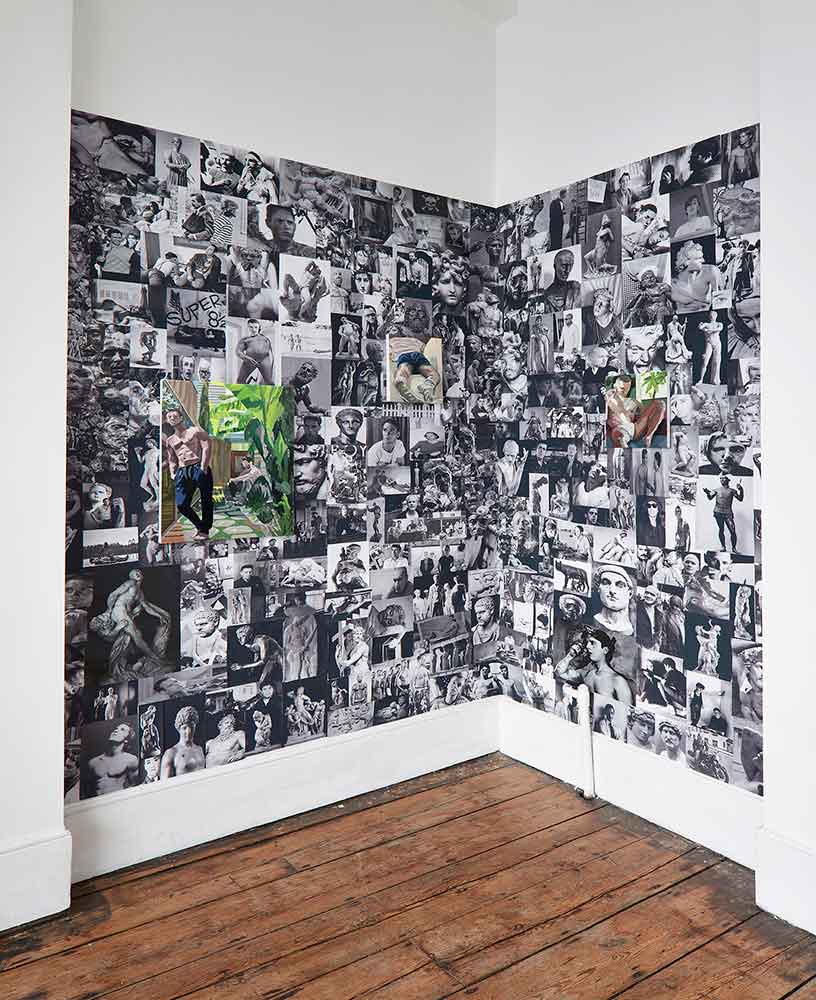

CBP: ‘Heads In Bloom’ and ‘Looted’ present collage in the form of installation with paintings placed onto a photomontage backdrop. They feel like a rich, darkly romantic homage to gay icons and evoke something of a luxury domestic interior or even a salon. How did this approach to installation come about? Was it an intended statement piece, or a result of intuitive experimentation and problem solving in the studio?

DL: That’s right, the ‘Looted’ collage was a way of paying homage to my gay heroes. They were about celebrating queerness and its contribution to art and culture in the 20th century. For me the collage reflected how contemporary gay lives grow out of a shared gay history. Yes, it was very much an intended statement piece. It came about for the Joe Orton exhibition I mentioned briefly before. I made the ‘Blue Boxers’ painting and two other paintings to place upon the collage and it was to form part of a three person show. The paintings were not large and I felt they needed something else rather than just a white wall. That’s how the collage came about. I also wanted to pay homage to the wall based collage that Orton and his partner Kenneth Halliwell created from stolen library books in their Islington Noel Road flat in the 1960’s. I wanted it to function like a ghost version of their collage. Also their collage had lots of reproductions of paintings, and I didn’t want that to compete with my real paintings so I filled it with portraits of queer icons such as Francis Bacon and movie stills such as Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising and Jean Genet’s ‘Un chant d’amour’.

Installed ‘What the Artist Saw: Art inspired by the Life and Work of Joe Orton’,

curated by Michael Petry and Dr Emma Parker at MOCA, London 2017

To me, it felt free and easy to be able to acknowledge my queer heroes and I celebrate the liberation of that, but who knows in our current epoch, our hard-won freedoms could change at any moment, so there is a darkness there too, it’s fragile.

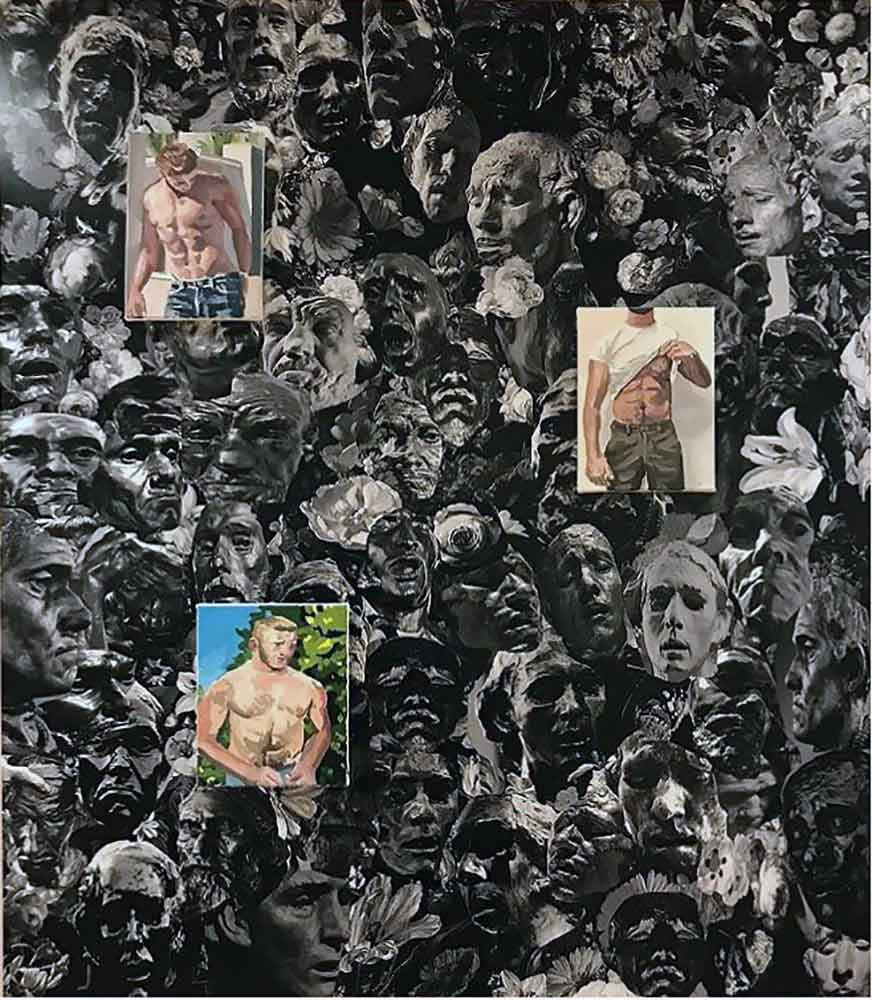

The ‘Heads in Bloom’ which is a large digital wall vinyl followed on from this. I was invited by the artist and curator Rosalind Davies to participate in a group show ‘Rules of Freedom’ at Collyer Bristow Gallery. For this show I took the one decorative element of the Looted collage, some heads taken from Rodin’s ‘Burghers of Calais’ and I multiplied them. For me, the Burghers represented freedom from oppression.

Installed in Rules of Freedom, curated by Rosalind Davis,

Collyer Bristow Gallery, London, 2018-19

CBP: Can you talk about your daily / weekly routine as an artist? Has Lockdown changed your approach and perspective to making work? You mentioned you a still on a protected list and still need to self-isolate.

DL: Yes usually I get to spend more hours in my Mile End studio but the lockdown has changed that. From March 2020 I could not get to the studio so I was at home. So whilst at home I continued making these watercolours (of which, ‘Boy in a Tree’ and ‘Lounging’ were a part) on my dining table and they’ve really sustained me. Also, because of the pandemic a commission I was working on was paused, so making these paintings and participating in the Artist Support Pledge on Instagram was and still is so valuable. It’s been a really vital network for me during this period.

The pandemic hasn’t really changed my perspective as such, if anything it’s underlined how vulnerable we are, not just myself but everybody. I do dislike that phrase I’m hearing a lot now ‘the new normal’. It’s so annoying, as normal’s really problematic, and it’s what got us into this. As you mentioned, I am on the shielding list. I have been going into the studio recently, but still only about once a week. I’ve also started to go to exhibitions again. Tomorrow I’m finally going to see the ‘Masculinities. Liberation through photography’ show at the Barbican. It’s a show that’s been extended and I’m so pleased about that. I originally was meant to go back in March, I bought tickets for the show and a panel discussion but in the end because of the virus I couldn’t go. Then they closed, so I thought I’d missed it. It’s such a timely show.