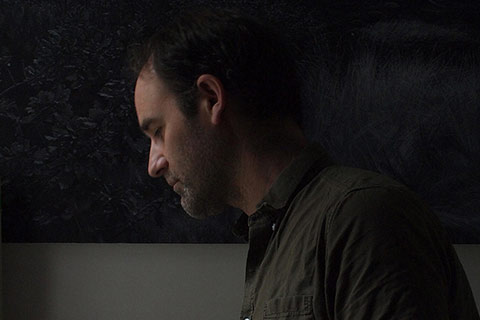

Andrew Litten: Artist of the Month

Artist of the Month August 2023:

Andrew Litten interviewed by Lucy Cox.

Andrew examines humanistic themes such as social alienation, love, sensuality, fear, anger, loss, ageing, addiction, paranoia and other identity disturbance. His gestural figurative paintings express a strong interest in the universal complexity of everyday existence.

LC: While in school, your interest in expressionist art led to life-drawing classes. However, you eventually decided against pursuing art education having found it ‘restricting’ and ‘claustrophobic’ and instead embarked on a journey across Britain, searching for diverse subjects. You observed people’s everyday lives and for several years created art at home, whether it was on the kitchen table, in the attic, or on the bedroom floor, rather than in an external studio. Although at the time you probably didn’t anticipate where these experiences would lead, looking back, what impacts do you think they had on you?

AL: Well, I think not continuing college was a mistake as I isolated myself too much. I don’t recommend it. However, I left art college early because I became tired of the ego-driven environment that made me uncomfortable. In the 1990s, art schools had an anti-painting agenda, maybe partly driven by Brit Art and Shock Art. I wanted to retreat to my life before college where I felt excited by the world around me. At that time, I liked the idea of creating a body of figurative work in an impromptu way rather than controlling my thoughts. By working on discarded objects, I connected with everyday life and, as a result, created hundreds of works a year. I’m still discovering them in my parents’ loft when I visit! Emma (my wife) and I had children young, so I gave up on the idea of exhibiting art and quietly created for about a decade.

75cm x 50cm, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

LC: Could you expand on your idea of the studio as a ‘big sketchbook’ where you surround yourself with unfinished paintings, drawings, and other artists’ work?

AL: Yes, I like the idea that my studio is a big sketchbook that I can move around in. It’s fun but serious; the idea of being consumed by creativity where I’m mentally and physically engaged. The representations are usually life-size, so it becomes behavioural, too, as I am aware of my own body in relation to the work. I want my art to be charged with a current of connectivity and feel alive, like a mass of raw nerves.

LC: How would you define your approach to representing the human body? You are very much a figurative artist.

AL: My approach to the human body is focused on creating an emotional reading of representation. Whilst descriptive information is important, it shouldn’t stop the flow of engagement or disrupt the reading experience. Although this may seem simple, it takes time to navigate through an abundance of visual information. The depth of emotion emerges through contemplation and reassessment of life experiences. To truly convey visual emotion, one must take risks and embrace change. In my work, the figure can undergo radical shifts in position or shape as the artwork evolves. I must embrace these changes and support them compositionally and anatomically. This is crucial if one wants to authentically represent something in a tangible and convincing way, going beyond mere stylistic choices. The face holds vital significance for me. We instinctively read people’s faces to understand their thoughts and emotions, primarily focusing on the eyes and mouth. I find it compelling that the human body is the most powerful and timeless model of expression and enjoy the process of finding my own path within a genre that carries historical weight.

licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Photo courtesy of the gallery.

LC: Do you think that your art mirrors yourself at times?

AL: That’s funny! To be honest that is such an annoying question! No, it’s funny, really! I’m laughing! I hate it when people assume all my work is just about me! I know you didn’t mean that though.

I’ve recently started my first large-scale self-portrait, although I don’t want to put myself at the centre of my creativity. Instead, I aim to explore outwardly for broad connections and an emotional range. The subjects of my work are mainly drawn from people I know, allowing me to develop ideas based on their experiences as well as my own perceptions. I love the tension that arises when art serves as a medium for multiple perspectives. While I’m reflected in the process, the act of reaching out is essential. I’m particularly drawn to the idea that art can signify a longing to connect.

LC: I understand why you wouldn’t want to put yourself first. Art is often perceived as a self-oriented activity, so it’s refreshing to encounter artists who decide to take a universal approach to making.

It’s difficult not to feel anxious and overwhelmed sometimes. Social media platforms are apparently designed to bring friends, family and like-minded individuals together but are we truly connected to each other at all? For me, your latest show at JDMalat Gallery, aptly titled ‘Connect’, with paintings such as ‘Disconnected’ and ‘Being Nowhere’, embodied this question.

Photo courtesy of JDMalat Gallery London.

Photo courtesy of the gallery.

LC: What are your habits? Do you have a daily routine?

AL: I don’t think so. My studio is currently at home, so I discover creativity easily. A predetermined technical approach bores me quickly; if I decide to do one thing, I usually start to see equal worth in doing the opposite. The subject becomes the driving force through this way of working. I have no habits or routines in the studio and instead prefer all-pure exploratory creativity.

I usually work quickly but there are times when it takes years to achieve the desired outcome. These extended periods often involve dramatic changes that breathe life into my practice, though. As a figurative artist, I think the aim is to trick the mind into meaningful recognition. There is a difference between merely perceiving an image and genuinely engaging with it on a deeper sensory level where the mind establishes a proper connection. My art should serve as the focal point of intensified activity, expanding fields of reference.

I continuously work with materials – paint, bronze, whatever it may be – until it feels right. Even if the results appear incorrect or unexpected, it must feel right. It’s all very precarious and mind bending at times.

LC: Who are your biggest influences?

AL: Well, life piles on experiences and influences. As a teenager, I was drawn to the gritty rigorous ethic of the School of London painters. These artists were meaningful during those early years, and I admired how dedicated they were to their life’s work. At the age of 16, I discovered London’s art galleries and regularly commuted from Aylesbury to Marylebone Station. I became a bit obsessed with the Marlborough Art Gallery in Mayfair, which at that time featured artists such as Auerbach, Rego, Bacon and Freud, all of whom I found inspiring. I guess this time was also significant because as a young person, it taught me the value of being connected intimately with art.

In my early twenties, I spent a lot of time in Leicestershire and found its county town museum’s collection of German Expressionist prints extraordinary. The emotive articulacy and directness of those expressionist prints became influential for my early work.

Today, I think it would be impossible to clearly say who my influences are since there’s so much available historically. In terms of contemporary art, I tend to gravitate towards female artists as, to me, they are typically more emotionally honest. Louise Bourgeois is particularly important to me. She reminds us that art should always be more visually interesting than anything that artists say and complex and physically diverse than any one exhibition can display. I love that feeling, that with a great artist, there is always more to be extracted and interpreted. Van Gogh is fascinating because no one can quite figure him out. I find confusion interesting. Matisse impresses me because only he could be the kind of artist to have created the work he did. I say that because I’ve been recently thinking about the purity in art, so this occurred to me with Matisse. It really moved me.

So many things can set off an idea, a film, book, or newspaper article. Sometimes, it’s a conversation. It’s bizarre how regularly the spark I need just appears in an unexpected way.

LC: You’ve depicted dogs repeatedly in your paintings that often appear calm or irate alongside male figures. When did you start using this motif?

AL: I started depicting animals very early on in my work; they become part of the domestic humble aesthetic I aimed for. In those days, I also used taxidermy animal parts, particularly birds, in assemblages, which was a lot of fun.

When I later transitioned into life size figuration around 2010, the level of engagement intensified, both physically and psychologically. To me, the animal references exist as an extension of the figurative identity, like smaller compartmentalised states that coexist with a different energy. It’s fascinating how animals utilise their senses in ways different from us. I sometimes try to creatively suggest this shift as a sort of alternative sensory stimulus to embody. It’s challenging to explain exactly what I mean now that I’m attempting to put it into words… but during the creative act, I can feel it. It makes sense why the animals need to be there.

Throughout art history, animals have often represented the complex relationship between humanity and nature. The line between humans and animals may be more blurred in our imagination than we perhaps realise. I use animal references to present broader anxieties related to the uncomfortable primitive instincts within us: group behaviour, wild freedom, our uncivilised aspects. Animals serve as valuable subjects for contemplation within art.

Photo courtesy of JDMalat Gallery London.

Photo courtesy of JDMalat Gallery London.

LC: That’s a good way of putting it: animals as an extension of the “figurative identity” and a way to engage with art. Someone – I can’t remember whom – described Francis Bacon’s dog paintings as “the anguish of contemporary life”, something which we can all relate to, perhaps now more than ever. I am reminded also of mythological hybrid creatures such as sphinxes. Half human, half feline, in Greek mythology, it’s said they symbolise mystery, enigma and brutality.

AL: Yes, brutality can be there. Lucas Cranach’s paintings of animals often have a curious blending beast and humanised qualities, particularly in his allegorical compositions. I love his painting Garden of Eden. Cranach’s paintings are oddly primitive and sophisticated, too, and I resonate with that.

LC: This is the first time I’ve seen you use sculpture. Have you experimented with it for a while? What is your approach to this medium in relationship to painting?

AL: I have always created three-dimensional work in addition to painting, although earlier on it primarily took the form of assemblage. When I shifted my focus to large-scale paintings, I started making clay models as references. I admire how sculpting engages different areas of the brain. My sculptures are standalone objects but often relate to specific paintings. Around three years ago, I realised that casting them in bronze could better reflect their intentions, and with the support of Anima Mundi [Gallery], I was able to bring this idea to life.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

LC: What inspired the exhibition and why the title ‘The Human Shadow (The Animal Smile)’? [Andrew’s latest exhibition at Anima Mundi Gallery]

AL: I wanted a title that was difficult to pin down as I enjoy the disconnect it creates in the mind, allowing space for interpretation. In the exhibition, I aimed to express emotions and instincts that are at times unexpected or defy logic.

On another note – and while I don’t want to go too far down the autobiographical route or explain everything from a personal perspective – it’s an unavoidable fact that I have been grieving a significant loss. The process of rebalancing and rewriting my cognition has had a profound impact on me and now I deeply feel the need for a meaningful connection with nature, people and creativity. Grief has opened new dimensions of vision. Although the exhibition has unavoidably become an expression of that experience, I think it carries a positive outlook. Although emotional connections can also be complex, confused or frustrated, I want my art to communicate this language of longing.

Self-taught artist Andrew Litten was born in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire in 1970. He currently works from his studio in Fowey, Cornwall. Solo exhibitions include ‘The Human Shadow (The Animal Smile)’, Anima Mundi Gallery, Cornwall, 2023, ‘Connect’, JDMalat Gallery, London, 2023, and ‘Impromptu’, Drill Hall Gallery, Canberra, Australia, 2018. Group exhibitions include Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize, De Montfort University, Leicester, 2020, and ‘Contemporary Masters from Britain: 80 British Painters of the 21st Century’, Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts Museum, Jiangsu Art Gallery, Nanjing, Jiangsu Museum of Arts and Crafts (Artall), Nanjing, and Yantai Art Museum, China, 2017/18. Andrew’s work is held in public and private collections both nationally and internationally.