Phil Illingworth: Artist of the Month, August 2025

Phil Illingworth selected and interviewed by Paul Newman for CBP.

This month’s interview discusses Phil Illingworth’s solo exhibition Juggernaut: ‘Bringing together works spanning more than fifteen years alongside new, never-before-seen work, Juggernaut presents a potent and timely exhibition by Phil Illingworth. Featuring drawing, drawing and painting in the expanded field, sculpture, and film, this body of work marks a compelling evolution in Illingworth’s practice – yet retains a clear and urgent thread that runs through it all: a profound unease with the social and political forces shaping our lives.’

CBP: Can you introduce the broad themes presented in your solo exhibition Juggernaut on show at Platform Gallery, Middlesborough Railway Station until the 7th August?

PI: It’s difficult to know quite where to start to be honest. I realised there was a lot I wanted to get off my chest so to speak, so it’s an intensely personal show. On the other hand – and this is the reason I wanted to show these works together – it addresses issues that affect everyone.

The exhibition somehow has its roots during the Covid pandemic. Like everyone else I was suddenly behind closed doors, isolated from the outside world. It should have been an ideal opportunity for me to concentrate on my practice, but instead I found myself going down a different path. Very early on there was speculation about the astonishing sums assigned to Track and Trace, and the whiff of corruption. I researched what that amount of money could buy, and it didn’t make sense. Early on I heard whispers about suspect PPE contracts and began digging around in Companies House and so on. Odd little businesses that were one day dormant with no money, the next with contracts worth £millions. All of this, along with stories of parties in Downing Street, Cummings’ eye-test trip to Barnard Castle, and etcetera, etcetera, etcetera. All the while people were dying. I became incredibly angry, amplified by the frustration of a terrible sense of helplessness. It was overwhelming, and I pretty much stopped making work.

I eventually had to find ways to force myself back into my practice, trying to channel my anger and frustration into something creative. Some of the works in Juggernaut are the result.

When the invitation for a solo show came through, I looked at my recent work, and work I knew I would want to make for this show. I also began to look at my older work. I became aware that there were threads running through that I hadn’t quite connected as consciously as others – followed by the realisation that I had been angry all along. Platform-A Gallery knew me best through my work with painting in the expanded field, so I was a little trepidatious when I approached them with the work I had in mind. Happily they were completely supportive.

CBP: Talk about the venue on the platform at Middlesborough train station and any considerations, challenges it presented?

PI: It’s a venue I know well, and I’m very fond of it. The gallery was created in 2011 as an adjunct to Platform Art Studios, and is a purpose built space created within Victorian former railway buildings. My first experience of it was in 2013 with North South Divine, a group show with Alison Wilding, Kate Davis, Annie O’Donnell, Deb Covell, Tony Charles, Boa Swindler, Chiara Williams, and me. North South Divine was co-curated by Wilson Williams Gallery and Platform-A Gallery, exhibited first in London, followed by Middlesbrough. I have subsequently taken part in other Platform-A group shows and an earlier solo show Apocalypso in 2016.

I worked closely with the curator, remotely at first, then in person at the venue for the installation days. There were a few minor technical considerations for Juggernaut, such as routing electricity to some of the works (there are two video monitors and two works which are powered), then curatorial considerations of course. It’s a large space, and there’s a responsibility to get the number and balance of works right.

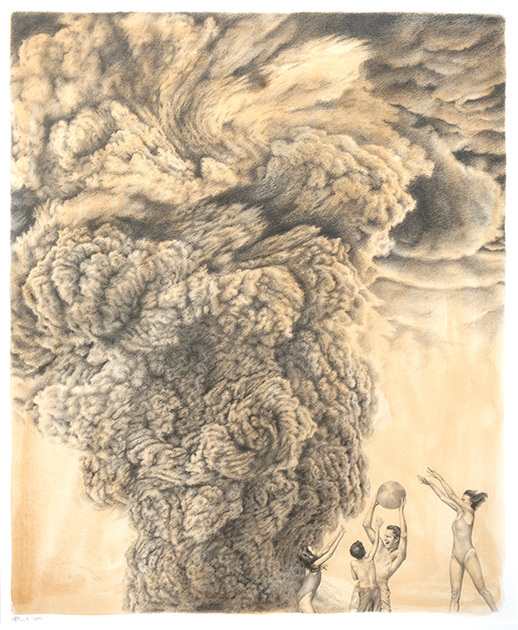

CBP: The title of the show is taken from the vintage styled pencil drawing Jugger Jugger Juggernaut, depicting a family ‘playing’ on the periphery of what seems to be an atomic mushroom cloud.

20 years ago I visited the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History in Albuquerque, New Mexico, near the atomic bomb test site. Presented in a case was a long panoramic cartoon depicting the everyday lives of factory workers constructing the bomb. Like a modern-day Bayeaux Tapestry, there was a calm passive style to the tone of the illustrations, like a pictorial instruction manual. The incongruous figures in your drawing reminded me of my memory of this artifact.

Can you talk about this work, (the frame seems conceptually considered), and the significance of its title?

PI: Jugger Jugger Juggernaut is onomatopoeic, intended to suggest the rumble of the enormous deity-bearing chariot ‘Juggernaut’, under the wheels of which devotees are said to have thrown themselves in ritual self-sacrifice.

It is the oldest work in the exhibition (2009), made before I began to move away from figuration. It probably encompasses everything in the show. I wanted the smoke cloud to be ambiguous – is it a nuclear explosion? A sandstorm? A tornado? There had recently been a huge fire on an industrial estate which lasted for days, and the enormous plume of smoke resulting from the fire could be seen from miles around. The cloud is a composite I made from stills I took from news footage, and the ‘nuclear family’ is a stock photo.

The hand-tinted paper is a nod to renaissance drawings in silver point and chalk on hand-coloured paper. The framed work sits on the floor, leaning against the gallery wall.

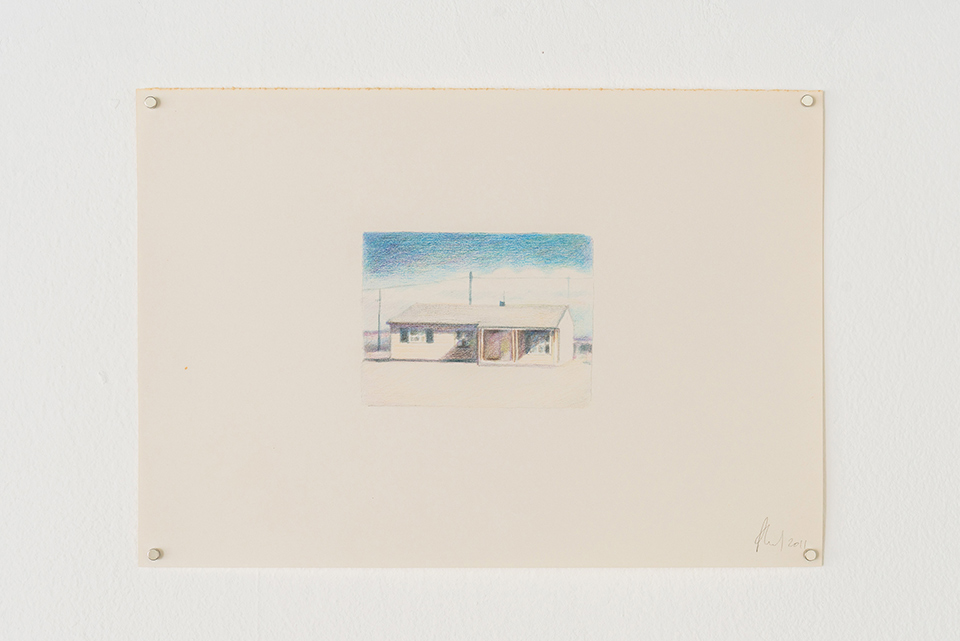

CBP: Connected to this work, I’m happy just to dance with you presents a different style of colour pencil drawings evoking the soft colour and grainy patina of 1955 film footage of nuclear tests on fabricated buildings. The choice of medium and its gesture feels integral to the translation of this type of remote footage. Your medium choices and execution often feel conceptually rigorous, would you agree?

PI: It interested me that you made the connection with the work you saw in Albuquerque and Jugger Jugger Juggernaut. This (from 2011) follows in its footsteps. Many of us were brought up with the threat of imminent nuclear war. It was a part of our lives: government issued ‘Protect and Survive’ leaflets, public information films on TV, Raymond Briggs’ When the wind blows.

The threat seemed to have almost gone away for a while.

I’d seen the footage of the nuclear tests from where these drawings originate many times. There’s an uncomfortable incongruity between the carefully chosen range of typical domestic buildings constructed as exact replicas – right down to soft furnishings and real refrigerators – solely for the purpose of destroying them to assess the impact of a nuclear blast on infrastructure. I wanted to reflect that, including the era-specific colour of the film.

Yes, you’re absolutely right: the medium choices and execution are part and parcel of one another.

CBP: As a historical shift Il voce (The voice) ‘uses the same processes and techniques used in religious sculpture, particularly Spanish, dating from the 16th century and still practiced today. The figures are hand carved from solid lime wood and painted (‘encarnaciones’) on a gesso ground.’

Are you self-taught in hand carving techniques? Can you discuss the meaning and ritual of choosing this technically challenging route of craftsmanship rather than 3D printing or presenting a ready-made assemblage?

I’m reminded of Mark Wallinger’s State Britain which presented the protest camp of the late Brian Haw an anti-Afghanistan War activist, inside the hall of Tate Britain. The original camp was sited for five years outside the Houses of Parliament, before the courts ordered forced eviction. Except Wallinger’s work was a meticulous, hand-crafted studio fabrication, not the actual camp. It ignited a number of ideas about the notion of time, solitude and dedication to an idea. Can you identify with this in the production of your work?

PI: Absolutely. You asked about choices of medium and execution in the previous question, and to expand on this it is essential, to me at least, that the concept, the medium and the process are fully integrated. However this often means I put myself in a position where I need to learn new skills in order to execute an idea, and this is one of those occasions. Prior to this I had only done small-scale carving – no more than whittling really, so this was admittedly ambitious.

I really got my teeth into it – I made detailed 1:1 scale drawings of elevations and sculpted actual-size maquettes from plasticine of key elements such as the head and the hands; I researched techniques as thoroughly as I could. Serendipitously, as I started my research, an exhibition at the National Gallery The Sacred Made Real provided an unexpected opportunity to study a collection of 17th-century Spanish religious polychrome sculptures.

Sometimes I’m fine with using the ‘ready made’ or what might be perceived to be a ‘short cut’, but it has to be with conviction. More often, hands-on engagement with the process, whatever that might be, is fundamental, and during that time also reflecting on the traditions, history and contexts that accompany.

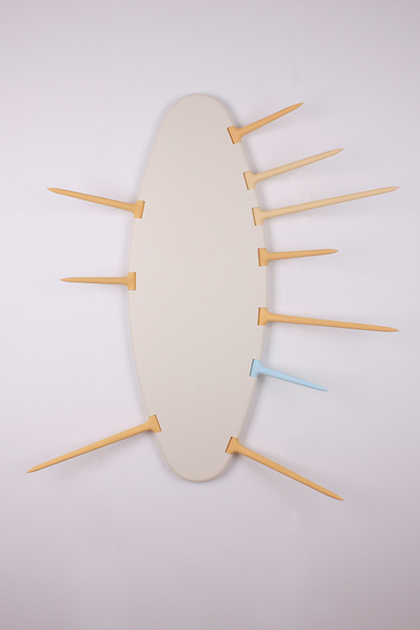

CBP: Where Shadows Are Cast feels like a more improvised piece juxtaposing church architectural facades with the distinctive coloured spikes that is a reoccurring motif throughout your work. Can you talk about the lineage of this piece with previous works and the thinking and making process behind it?

PI: Concurrent with considering the history of the church as a patron of the arts, a recurring theme in my work is the church, in all its forms, as an institution. I don’t have a particular issue with faith as such, it is the power of institutionalised religion and the alignment of church and state that I want to cast a light on. I came across the quatrefoil panels (which are from a rood screen) at a vide grenier in France fifteen or twenty years ago. It was inevitable that I would use them in a work, it was a question of what. The ‘when’ turned out to be very much later.

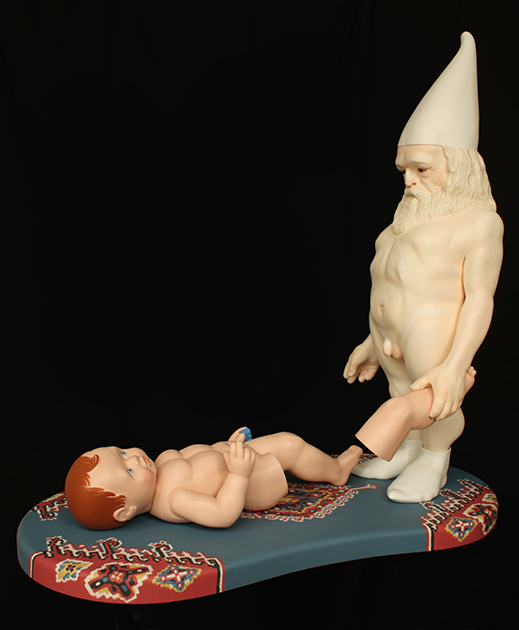

The blinding of Polyphemus, MDF, primer, enamel paint, acrylic paint, wood, acryl rod, 122 x 122 x 25cm (variable), 2013

The blinding of Polyphemus (detail), MDF, primer, enamel paint, acrylic paint, wood, acryl rod, 122 x 122 x 25cm (variable), 2013

One day, some years ago, I suddenly realised that I had used spikes a lot. It wasn’t exactly something I’d planned, it may have been more subconscious. There had been earlier hints of possible incubation of them as an idea, but the first use in a conscious way was in The blinding of Polyphemus (2013). It has articulated spikes which can be moved, and there’s a tacit threat to the viewer which interested me greatly.

Bringing the quatrefoil panels and spikes together came about after countless abandoned ideas and trials, and studio play. This, as opposed to the development and refinement of spontaneous ideas, is another side to my practice.

CBP: As this is Contemporary British Painting, of which you are a member, let’s discuss the work most identifiable as a painting, Confluence I which takes the form of a minimalist / modernist abstract painting as object, exploring mimetic fabrication of form and surface. Can you talk about this work as part of its series?

PI: I’m probably best known for painting and drawing in the expanded field. I’d wanted an earlier work to look as though it was made of paint – the Confluence series came about as an extension to this. I wanted to explore paint as object and notions of representation. Of course a painting is often something it’s not – it’s a manifestation of an idea, not the thing.

Confluence I is in the show because it is something pretending to be something it is not.

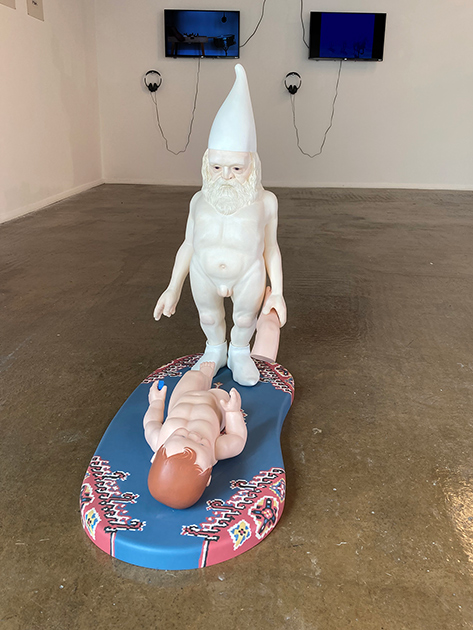

CBP: Carapace presents an immaculate material veneer, like a facsimile of a porcelain human turtle; odd, supersmooth, naturalistic and uncanny. It feels loaded with ideas of contemporary technologies, post human and timeless notions of subservient humanity from the building of the Pyramids in Ancient Egypt. Do you consider this a central piece in this body of work, like an iconic effigy?

PI: It is a central piece, yes. It’s inspired by an ancient Aztec figure of a turtle ‘Macuilxochitl (Xochipilli)’. According to a book I have, to the Aztecs, the turtle is “a symbol of lubricious, bragging cowardice: hard on the outside, soft and slimy within”. My interpretation is this human figure, entirely naked apart from an inadequately small shell. It represents every single one of us, whatever our situation or circumstances.

Carapace, polymer clay, approx 38 x 25 x 18cm, 2025. Image courtesy of Platform-A gallery, photograph Rachel Deakin.

Carapace, polymer clay, approx 38 x 25 x 18cm, 2025. Image courtesy of Platform-A gallery, photograph Rachel Deakin.

It’s made from polymer clay which must be baked to harden it. The baking was carried out multiple times, and the spectacle of this naked man in the oven, especially when it was on its back with its legs in the air, was the cause of much hilarity in our house.

Embracing technology further, I had the figure laser-scanned, and have had a limited edition of 25 quarter-scale versions 3D printed. Called Carapace 2, the bare backside of one of these greets visitors as they enter the gallery, setting the pace of what is to come. The curator Olivia and I took great delight in that.

CBP: Are there any other specific works from the exhibition you would like to talk about?

Most of the works in the exhibition are the result of a slow burn – in many cases, literally years of contemplation. There’s one in particular though, that is very much more spontaneous. Two years ago I was filming around The Isle of Portland off the Dorset coast. I had nothing specific in mind – it was a beautiful, warm sunny day and I was filming the sea crashing onto the rocks. I could hear children’s shrill voices and the deeper drone of adults in the background. It suddenly struck me that right now there are refugees risking their lives taking to these same seas. The thought sent me reeling, and the outcome is Sanctuary.

CBP: There’s an intentionally disparate set of styles and approaches on display. It’s like you are a curator of a museum of ideas and concepts, careful not to cultivate an identifiable artistic style that clouds the purity and creative autonomy of individual works.

It connects with conceptual artists from Marcel Duchamp to Ryan Gander, responding to the necessity of the individual piece. There’s a detached quality to this approach, presenting a museum of artefacts. There’s something intuitive with the idea of a museum, presenting concise documents, critiquing histories and political and societal forces. Can you talk about the overarching non style of works in relation to your concepts?

PI: I’d say Juggernaut is necessarily disparate in order for me to achieve what I wanted, but that did present me with some potentially difficult decisions. I mentioned earlier that I’m probably best known for painting and drawing in the expanded field, and for most of the last 15 years I have avoided showing, and eventually making, anything which I felt was outside that area, focussing instead on how far I can push those core interests. I had concerns that the apparent disparity in this exhibition might suggest confusion, perhaps. But these works are all created by me, and they fit resolutely into the themes I wanted to highlight. I have absolute faith that everything is in the show for a reason. I appreciate your analysis very much.

CBP: This retrospective exhibition follows a solo exhibition nearly 10 years ago in 2016, Apocalypso, presented at the time of Brexit. Would you like to future speculate on the themes your solo show in 2035 will explore?

PI: The title Apocalypso hinted at what was happening at that time and was, perhaps, inadvertently prophetic. Firstly, I hope I’m around in 2035. Secondly I’d hope I will have less cause to be so angry, but pragmatically I fear that’s much less likely.

My head is still full up, so for now, I need to take stock.

Phil Illingworth has exhibited in the UK, the USA, China, and in Europe including the 53rd Venice Biennale. In addition to private collections, works are in public collections in the UK and China and, in 2019, the collection of the Yale Center for British Art, the largest and most comprehensive collection of British art outside the United Kingdom.

Alongside Juggernaut, he is currently showing in Advanced Contemporaries II at IONE & MANN Gallery in Mayfair. Exhibitions in the past year include Clinging On at Glassyard Studios, London, Art of Living at Hypha Studios, Mayfair, London, ING Discerning Eye at the invitation of Paul Carey-Kent, The Mall Galleries, London, and Slow Painting at Studio KIND and Plough Arts Centre, Barnstaple and Torrington.

Instagram @philillingworth