Plausible Objects / Difficult Things

Sam Douglas

It is interesting how you have selected some of my favourite CBP artists and also G.L. Brierley’s whose work I have been familiar with for some time. It is primarily the painting processes of these artists that I respond to, the result of sustained development and focus in the studio that, over time, has led to a particular vision that I identify with when I look at their work. I am similarly concerned with a very studio-based practice and the way in which things evolve over a fairly long period of time as various processes are brought into play. I like things to mutate and to be broken down and built up again so that a motif can have many reincarnations and be revisited on different sized boards (mostly small scale) again and again and with various degrees of chance involved.

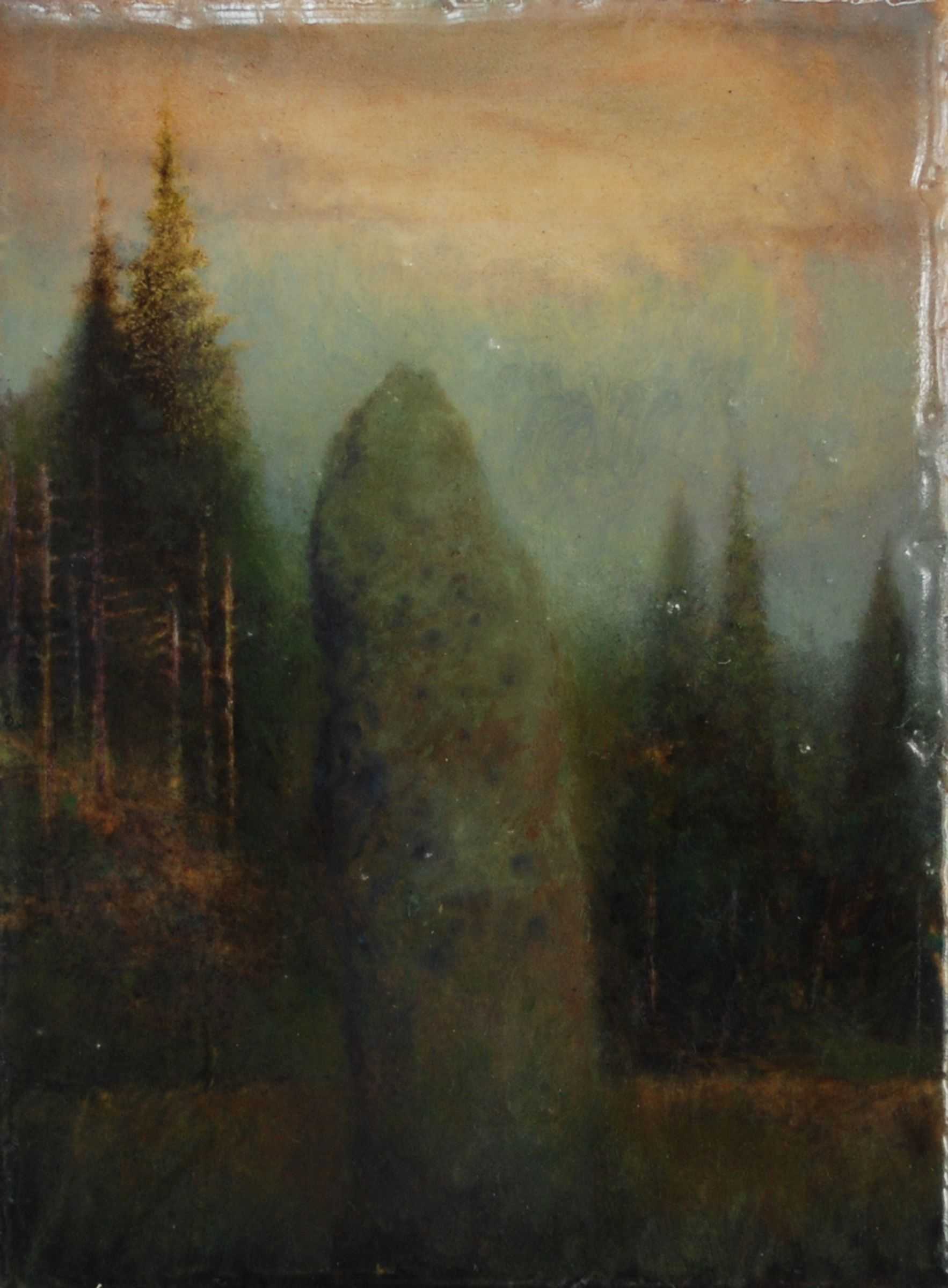

There is a melancholic quality to my landscape paintings which, following certain romantic motifs, are often of twilight. These I hope to disrupt through painting processes that involve various household varnishes, resin, pens, and the building up and sanding back and scratching that creates surfaces with which to play against them. It seems I can’t really get away from Romanticism in my work and all the artists you have mentioned (17thC Dutch Italianate landscape painters, the 19th century American luminaries, the Post-impressionists, Samuel Palmer and Peter Doig) have indeed had an influence over time. However, in my paintings there is often a feeling of claustrophobia or pollution that seeps into the work along with a general obscuring of the motif. I certainly enjoy twilight and I like the reductive quality that occurs in low light. Many such paintings often start off quite bright and detailed and end up obscured and dark, with just a few fragments of the initial image left visible. I can also forget what the initial elements were when a painting has been on the go for some time and if I sand into the surface, I may reveal a layer like an archaeologist scraping at the soil to reveal some lost artefact, often only a fragment.

Sometimes the small scale of the work and its reflective surface – built up of many transparencies – requires close observation and viewing from different angles whereby earlier layers of overpainting and buried elements become visible. I am often not aware of these myself until I remove my painting from the familiar lighting of the studio, maybe into a stronger spot-lit gallery space, where I will again see those previous layers.

I like your comment about the closer and longer one looks at painting the less familiar a shape becomes and the more distant from its origin. This is something I feel happens with many of my works as paintings progress, or not, as sometimes. Failure is a regular occurrence which builds the surface or foundations for the next attempt. There is an accretion of mistakes, alterations, a loss of interest, faith or patience that results in a hybrid composition or often a completely different image than the initial reference material.

I increasingly need to work from a specific landscape or place usually with ancient historical aspects, industrial too, and requiring a good deal of exploration and experience on foot. So, I would say that Graham Sutherland’s work from Pembrokeshire has a particular resonance for me at the moment. Having just completed a year’s residency in Northumberland I’ve decided to stay on in the area so as to continue focusing on what I consider to be a very interesting and layered landscape.

It’s good that you refer to ‘interior invention, a fictional twilight’ as this is certainly the case with most of my work. The initial reference is a starting point and the work will take its own course from there on. I’m often happiest when events occur in the surface that were unintended and which strike a balance between altered states, haziness, and faithfulness with the initial scene or a feeling that create a push and pull that shifts as the viewer moves around the work. The disruptive scratches, grittiness, wrinkles and other elements that are revealed upon closer viewing bear witness to the general struggle/reworking/erasure that much of the work goes through – the ‘objectness’ of the painting that you refer to.

© Sam Douglas and Frances Woodley

Image 1. Sam Douglas, Kronstadt Fort 1, 2016, oil and varnish on board, 38×29 cm. Photo the artist. © the artist.

Image 2. Sam Douglas, Standing Stone, 2018, oil and varnish on board, 16×11 cm. Photo the artist. © the artist.

Image 3. Sam Douglas, Chambered Cairn, 2018, oil and varnish on board, 22×20 cm. Photo the artist. © the artist.